1 | Executive Summary

Following four years of robust economic expansion, the FAO projects Ontario’s real GDP growth will slow sharply over the outlook,[1] reflecting weaker gains in household and government spending, residential investment and exports. The outlook for slower growth also occurs at a time of elevated economic risks that include heavily indebted Ontario households and an uncertain trade and investment environment.

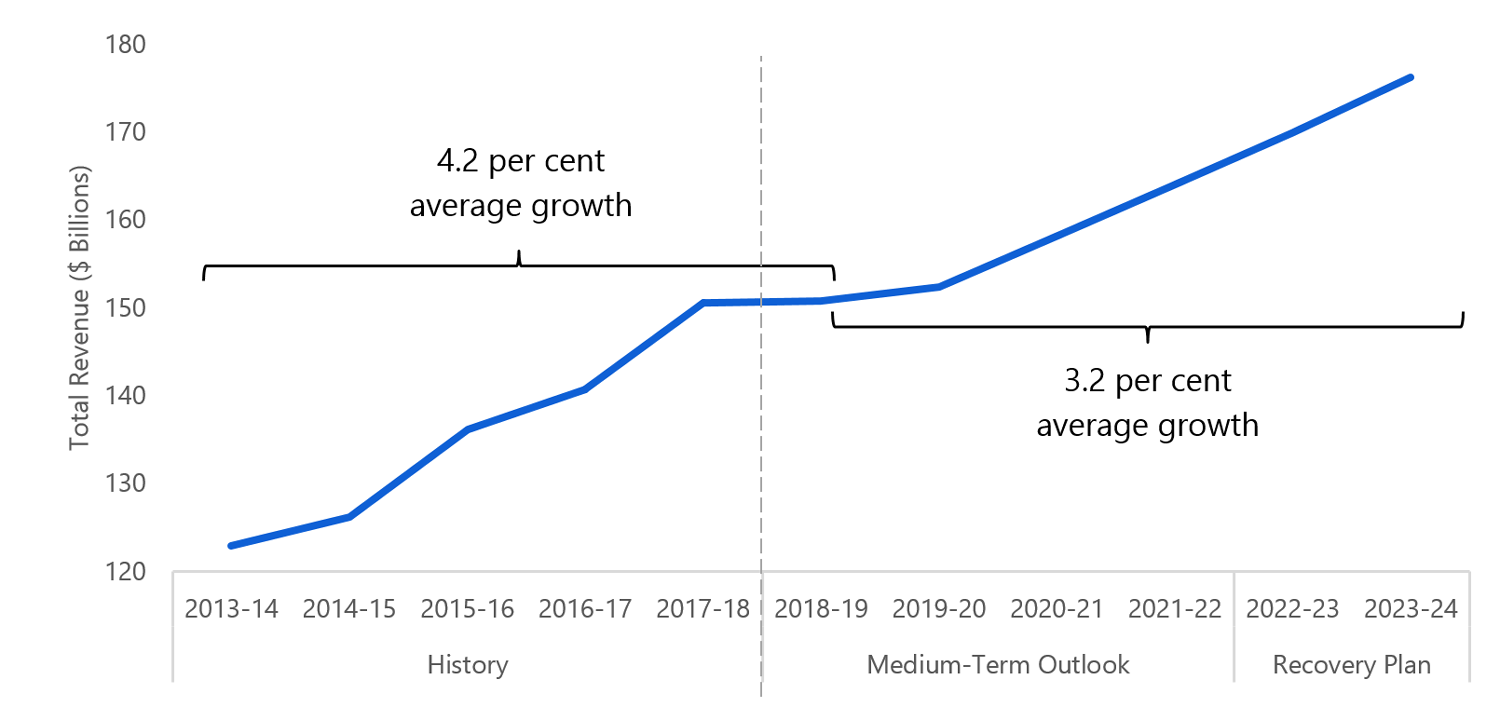

Weaker economic growth contributes to an outlook for slower revenue gains. The FAO projects the Province’s revenues will increase by just 3.2 per cent per year on average over the outlook, down from average annual gains of 4.2 per cent over the past five years.

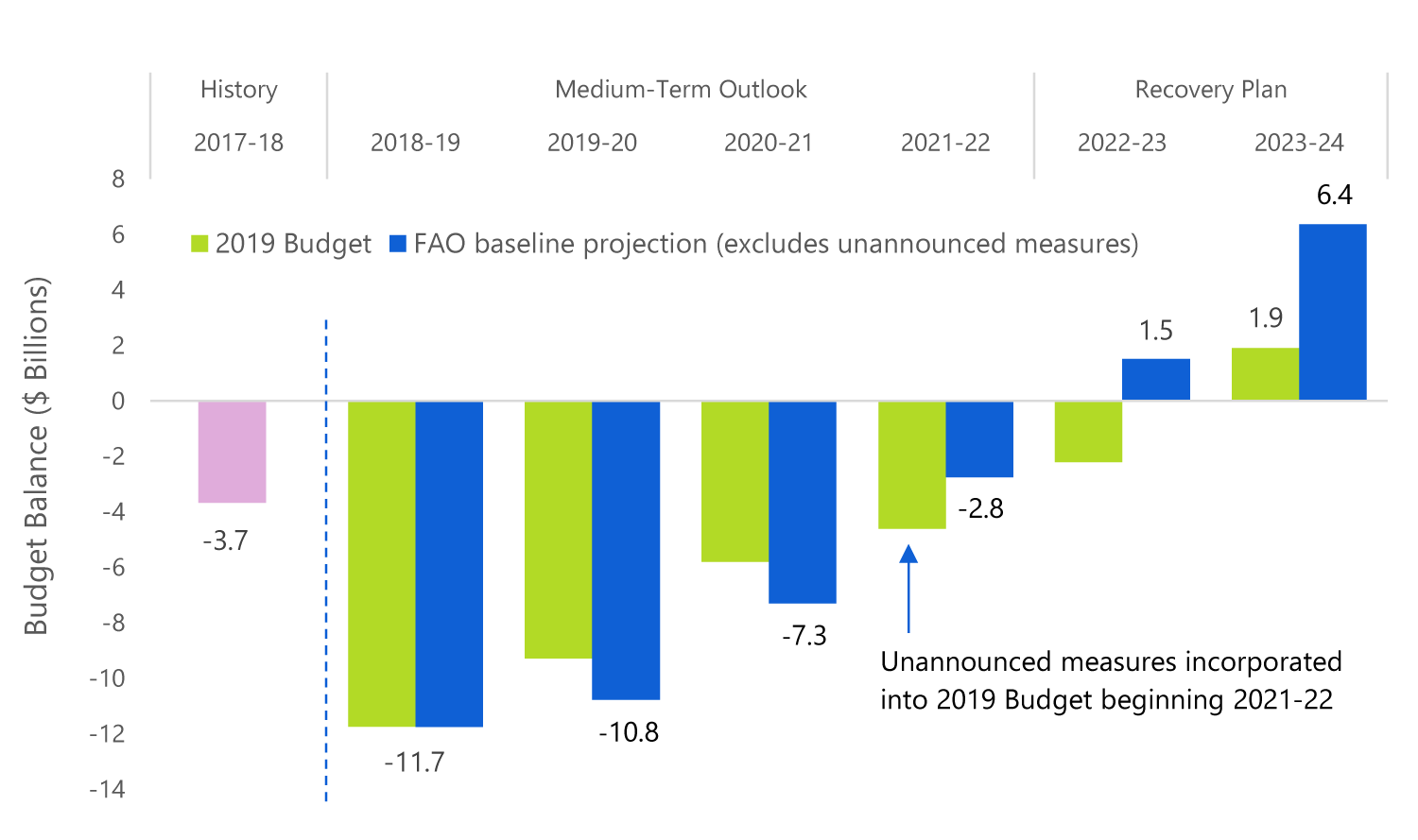

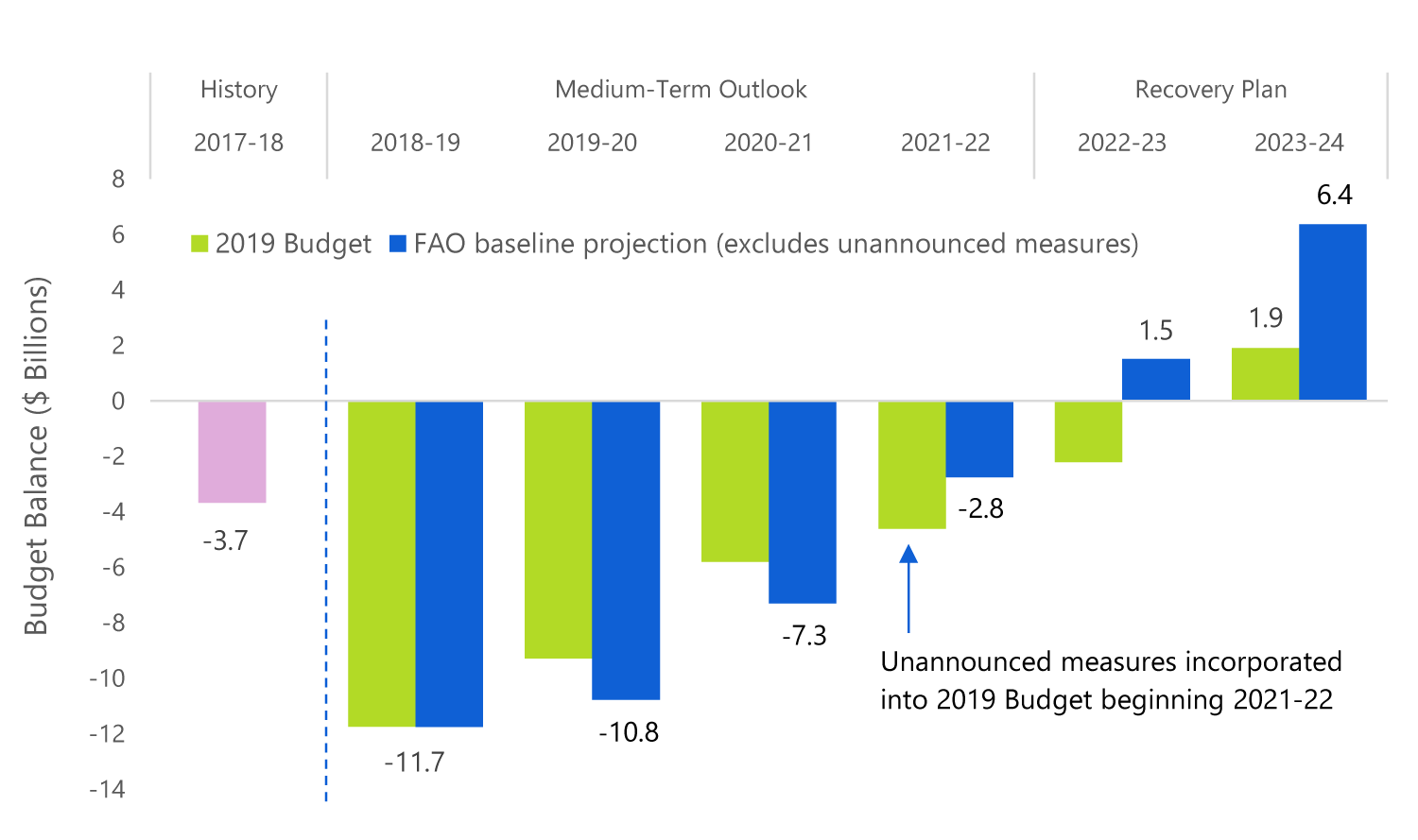

In the 2019 budget, the government committed to balancing Ontario’s budget by 2023-24. Given the outlook for modest revenue gains, the government’s plan for balancing the budget relies on restraining the growth in program spending to historic lows. However, the government’s spending restraint will also contribute to weaker economic growth over the outlook.

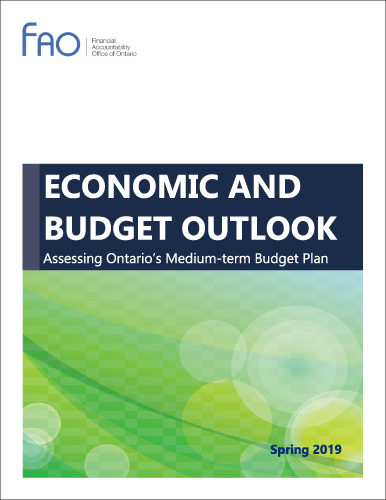

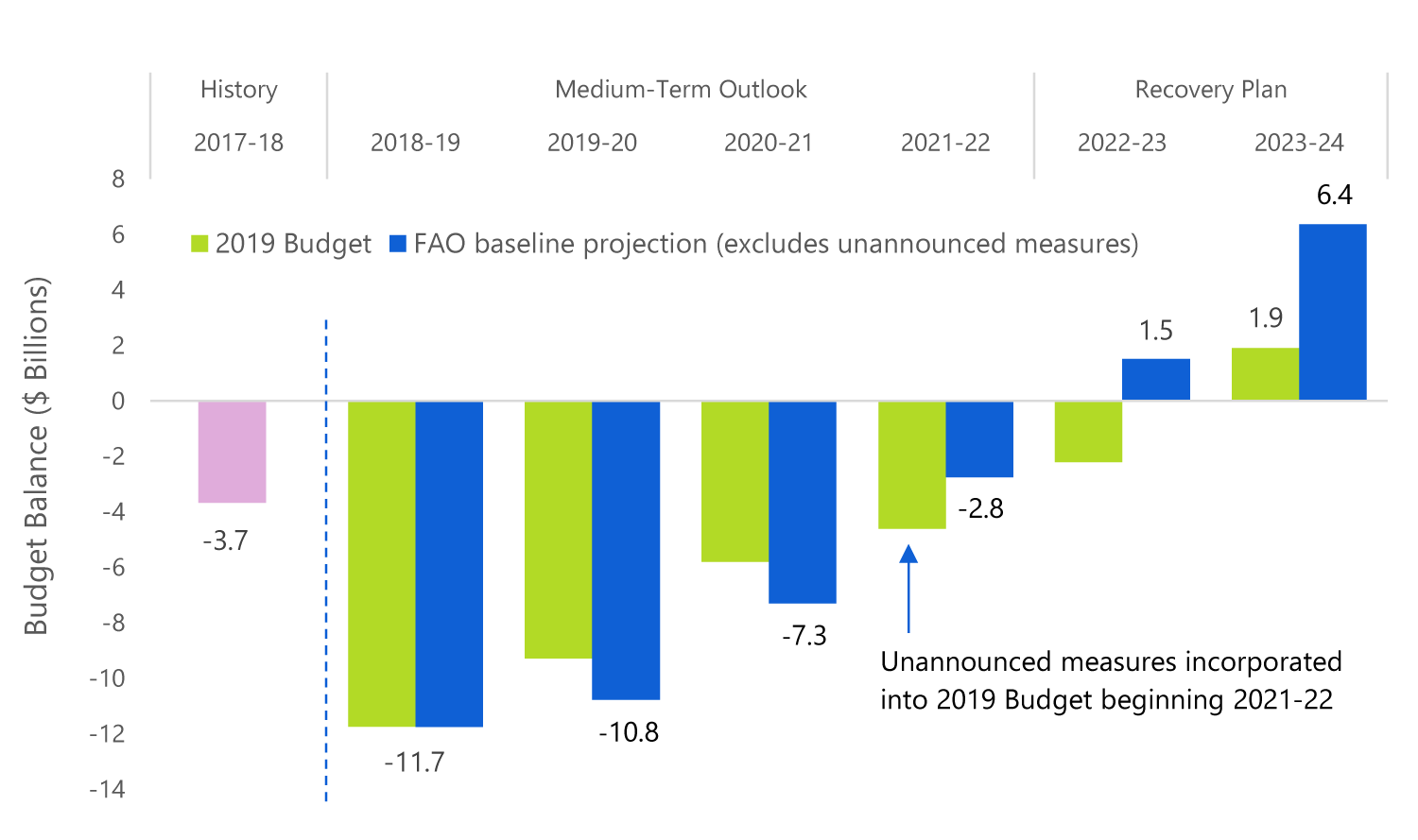

Under the FAO’s baseline projection,[2] Ontario’s budget deficit decreases from $11.7 billion in 2018-19 to $7.3 billion in 2020-21 and improves rapidly over the following three years, reaching balance in 2022-23 and a relatively large surplus of $6.4 billion by 2023-24.

The Province’s spending restraint would result in a $6.4 billion surplus by 2023-24

Note: Budget balance is presented before the reserve.

Source: Ontario Public Accounts, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

In contrast, the 2019 Ontario Budget projects smaller deficits over the next two years due to the government’s more optimistic outlook for revenue growth. Importantly, beginning in 2021-22, the 2019 budget incorporates provisions for unannounced revenue reductions and spending measures.[3] Although these unannounced measures would lead to higher deficits and add to Ontario’s debt, the Province would still achieve a balanced budget by 2023-24, due to its plan to significantly restrain the growth in program spending.

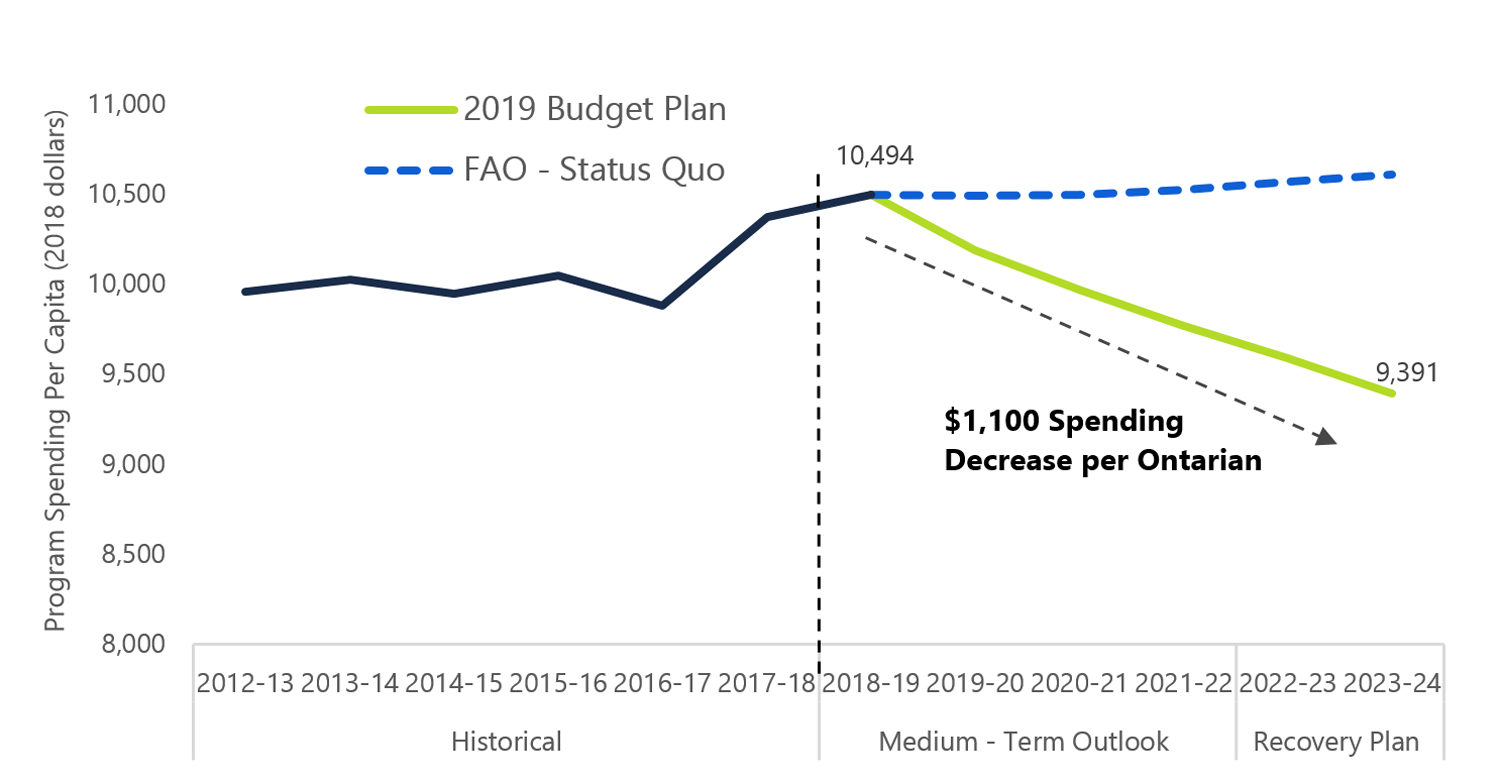

Specifically, the government plans to hold program spending growth to just 1.0 per cent on average over the next five years – which would be the slowest pace of spending growth since the mid-1990s. As a result of this restraint, provincial spending on public services would be reduced by $1,100 per person (or by more than 10 per cent) over the next five years.

The 2019 budget plans to lower program spending by $1,100 per Ontarian by 2023-24

Source: Ontario Public Accounts, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

To reduce the growth in program spending, the 2019 budget introduced a broad range of policy changes that included reforming OHIP+, increasing school class sizes, reforming social assistance and improving public sector procurement. The government expects that its policy actions would deliver “savings or cost avoidance” equal to about 8 per cent of program spending, on average, over the next five years.[4]

To assess the Province’s plan to achieve these savings, the FAO reviewed the detailed spending changes proposed in the 2019 budget. The FAO’s analysis suggests that the policies included in the 2019 budget to reduce program spending – if realized – would be largely sufficient to achieve the government’s spending plan over the next two years.

However, the FAO estimates that additional cost savings of almost $6 billion would be needed to achieve the 2019 budget’s spending plan by 2021-22.[5] Overall, the FAO was able to identify roughly half of the savings required to achieve the 2019 budget’s spending plan. This implies that significant future policy decisions will likely be needed for the Province to achieve the 2019 budget’s spending projections starting in 2021-22.

The 2019 budget’s fiscal plan takes place in an environment of elevated economic risks and depends heavily on the government’s success in limiting spending growth. If Ontario’s economic performance is worse than expected, or if the government is unable to meet its spending targets, it is unlikely the government would be able to meet its commitment of balancing the budget and also implement the new provisional measures assumed in the budget plan.

2 | Economic Outlook

Overview

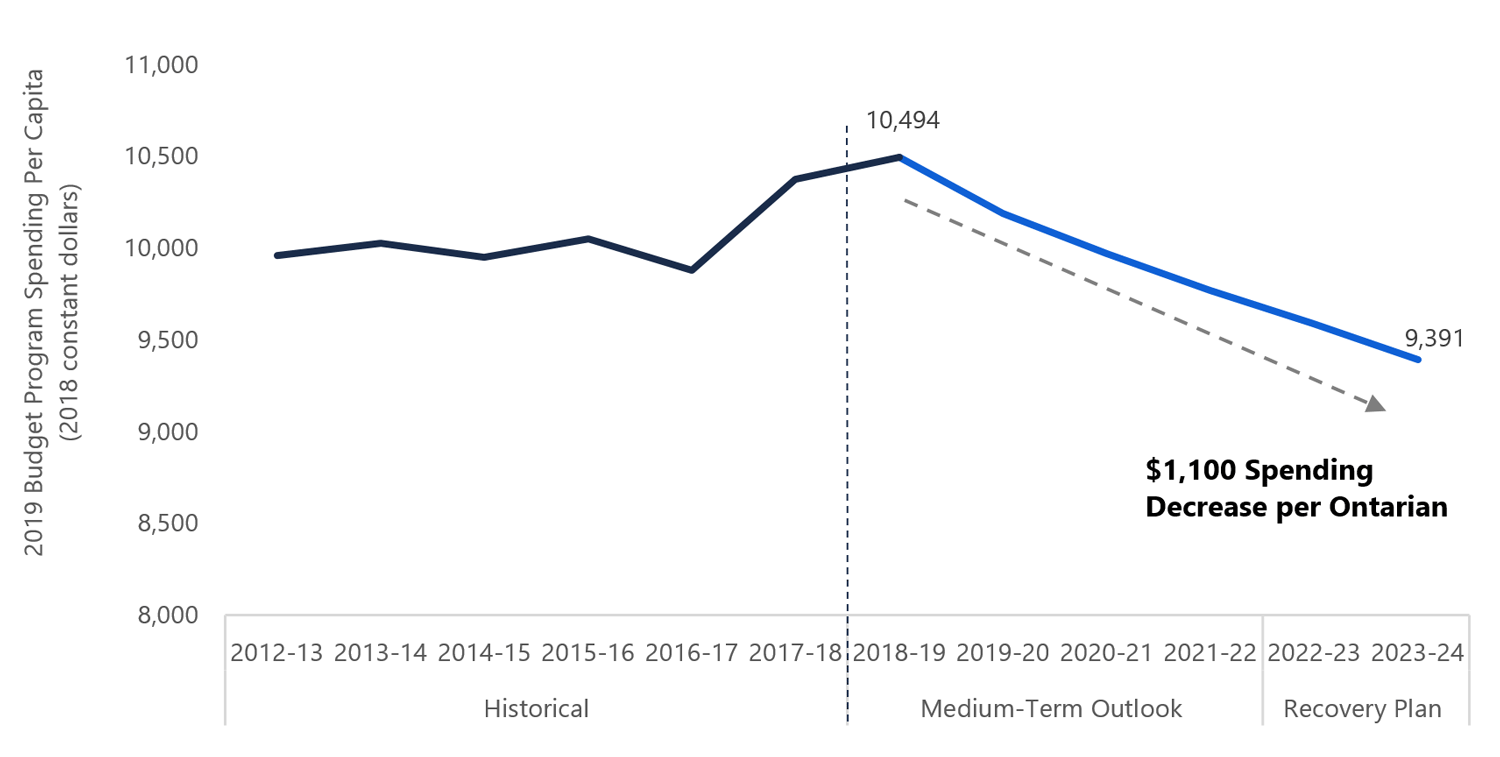

Following four years of robust economic expansion, Ontario real GDP growth moderated to 2.2 per cent in 2018.[6] In 2019, the FAO projects that growth will further slow to 1.4 per cent, reflecting weaker gains in household spending and exports, continued declines in residential investment and Ontario government spending restraint. Ontario’s labour market performed strongly in 2018 and the FAO projects steady, continued employment gains for 2019.

Over the outlook, the FAO projects a more modest pace of growth for the Ontario economy, with real GDP rising at an average rate of 1.6 per cent per year from 2019 to 2023. Elevated levels of household debt will dampen growth in household spending and residential investment, while a slowing US economy is expected to constrain Ontario’s business investment and exports.

Nominal GDP – the broadest measure of the tax base – increased by 3.4 per cent in 2018, down sharply from average gains of 4.4 per cent over the previous four years. Slower growth will continue into 2019 and 2020 with nominal GDP projected to grow by 3.2 per cent. Beyond 2020, the FAO projects nominal GDP growth will recover modestly to average 3.5 per cent from 2021 to 2023.

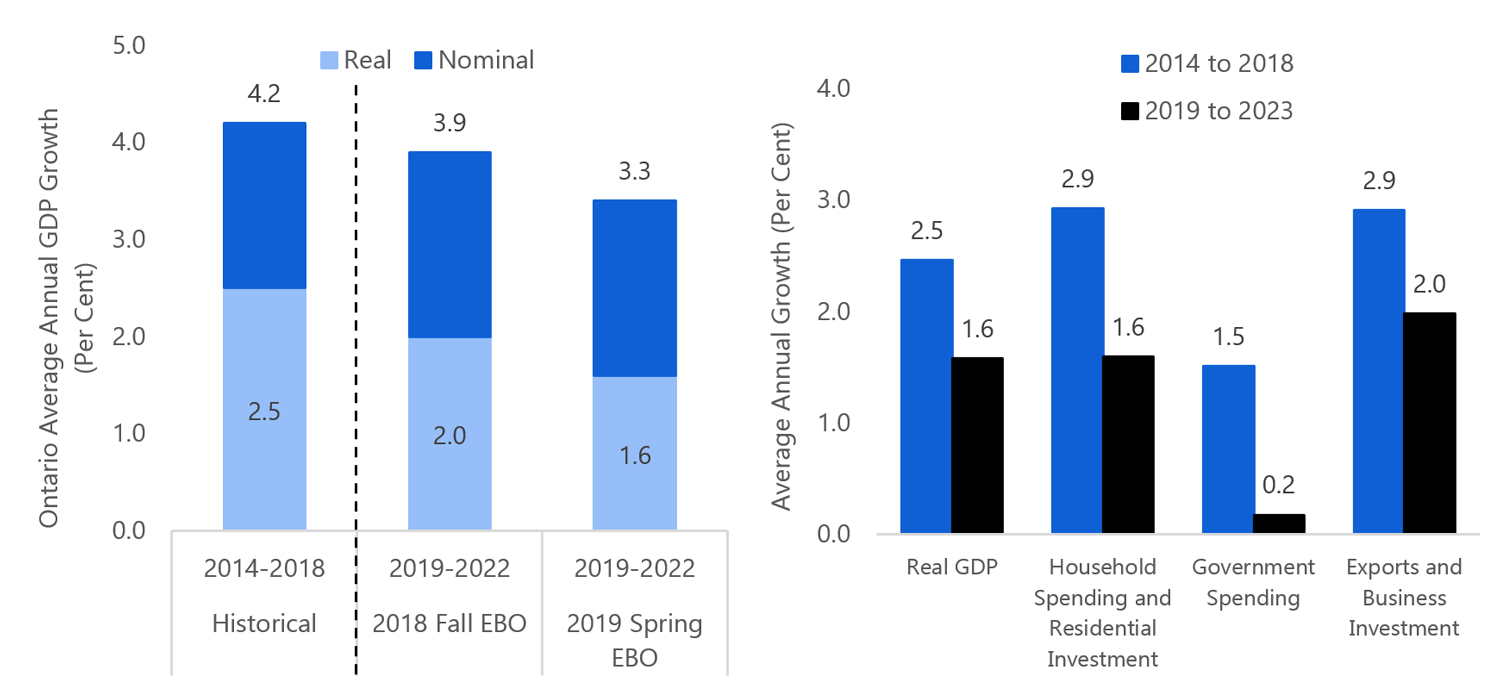

Economic growth is slowing in Ontario

Source: Statistics Canada, Ontario Economic Accounts and FAO.

The Ontario economy continues to face a number of risks from both domestic and foreign sources which could lead to even slower growth. These risks include a more pronounced slowdown in consumer spending and housing investment, uncertainty in global trading relationships which could continue to hold back business investment, and the potential for even weaker-than-expected growth for the global economy. Each of these risks could lead to much slower growth for the Ontario economy than currently forecast by the FAO, negatively impacting the Province’s fiscal outlook.

Global economic outlook has declined

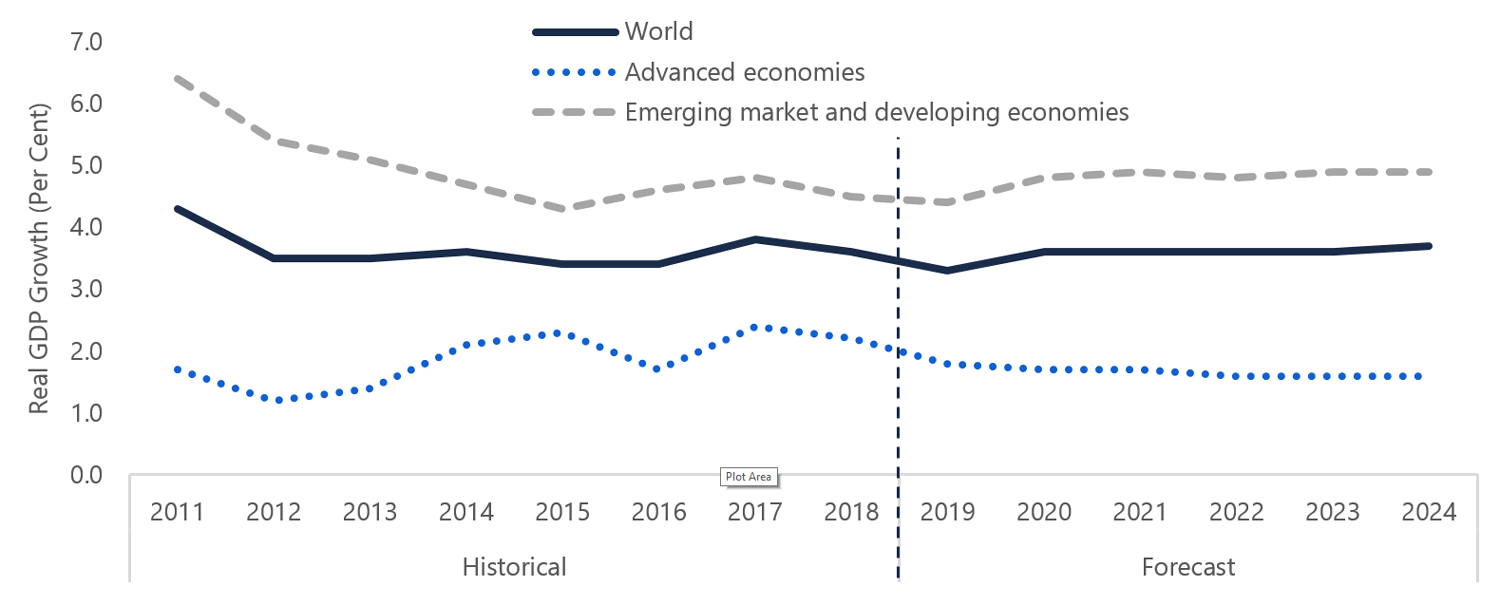

The global economy grew by 3.6 per cent in 2018 but slowed in the second half of the year due to tighter financial conditions, tensions in international trade and country-specific developments such as Brexit negotiations in the UK and fiscal instability in Italy. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects that global economic growth will slow to 3.3 per cent in 2019, a considerable downward revision from the forecast last fall.[7] However, the IMF anticipates a modest recovery beginning in the second half of 2019 that will carry over into 2020, as central banks pause further interest rate increases and trade relations improve. Over the outlook, the IMF projects that global economic growth will average 3.6 per cent annually.

Steady global growth expected over the outlook

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April 2019.

For advanced economies, growth is expected to slow from 2.2 per cent in 2018 to 1.8 per cent in 2019, reflecting more moderate growth in most G7 countries.[8] In particular, weak growth was widespread across the Eurozone last year. Disruptions in the German auto industry, widespread protests in France and a recession in Italy have all contributed to Europe’s diminished economic prospects. In the longer term, aging labour forces in many advanced economies are expected to weigh on GDP growth.[9]

For emerging market and developing economies, growth is expected to edge down from 4.5 per cent in 2018 to 4.4 per cent in 2019 due to tighter global financial conditions, weaker oil prices for commodity exporters (namely the Middle East and Russia) and country-specific factors such as macroeconomic stress in Turkey and political instability in Venezuela.[10] Prospects for emerging Asia and emerging Europe are mixed while a strong recovery is anticipated for Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa.

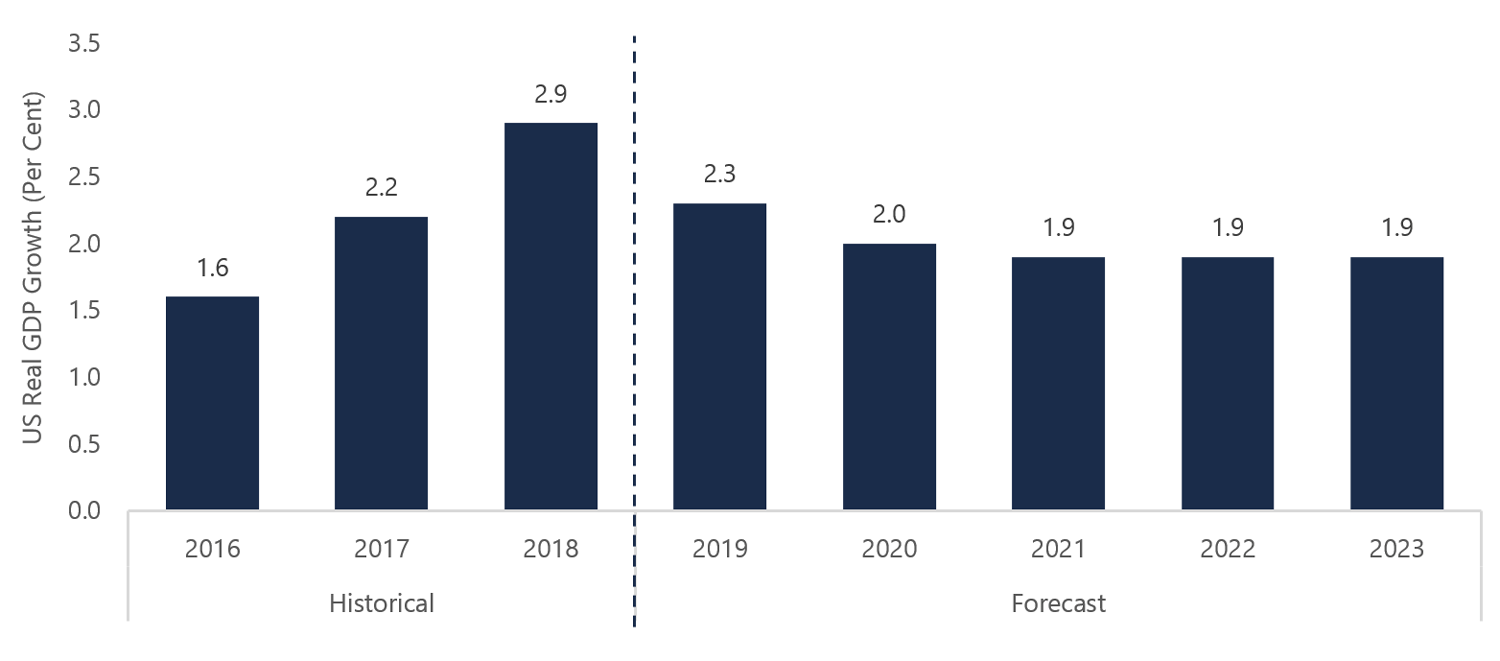

United States

US economic growth was particularly robust in 2018 with real GDP rising 2.9 per cent. Going forward, US growth is projected to moderate to 2.3 per cent in 2019 as the effects of the 2017 tax cuts and federal stimulus subside.[11] Both consumption and investment growth are expected to slow, as last year’s strong income gains moderate and higher borrowing costs weigh on business profits and investment.[12] However, the trade outlook has improved somewhat, with both the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) and a comprehensive trade deal with China on the horizon.

In March, the Federal Reserve revised down its inflation and GDP forecasts, following a statement that it would be ‘patient’ about future interest rate increases.[13] As a result, further increases in the US policy interest rate are unlikely in 2019. At the same time, uncertainty in US trading relationships and mounting federal government debt continue to weigh on the US outlook.

US economy expected to moderate as fiscal stimulus ends

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal Open Market Committee and FAO.

China

Chinese economic growth slowed noticeably in the second half of 2018 as household spending, domestic investment and export demand faltered.[14] Despite efforts by the Chinese government to encourage economic growth with tax cuts, infrastructure spending and monetary stimulus, the economy is expected to slow further in 2019 in response to tighter financial regulations and US tariffs on Chinese goods.

Going forward, a high debt burden and a challenging trade relationship with the US are key risks for the Chinese economy.

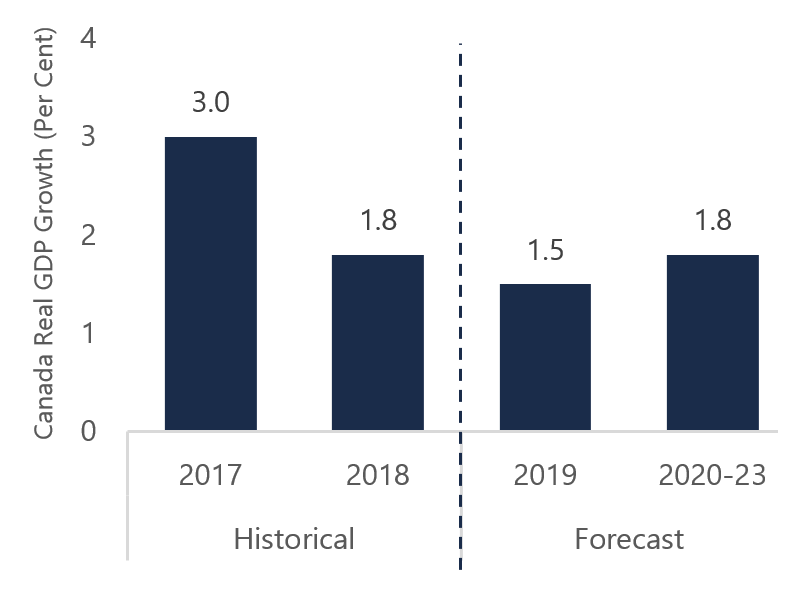

Canadian growth to slow in 2019

In 2018, Canadian real GDP increased by 1.8 per cent, down significantly from a 3.0 per cent gain in 2017. Slower Canadian growth was largely a reflection of weaker household consumption and residential construction, as well as lower energy sector output in the second half of 2018 as a result of the sharp drop in Canadian oil prices.

In 2019, Canadian real GDP growth is projected to slow further to 1.5 per cent, reflecting continued moderation of household consumption and business investment. Over the outlook, real GDP growth is expected to recover, increasing by 1.8 per cent per year, supported by a steady labour market, stable energy sector output and improved trade conditions.

Canadian real GDP growth to slow in 2019

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

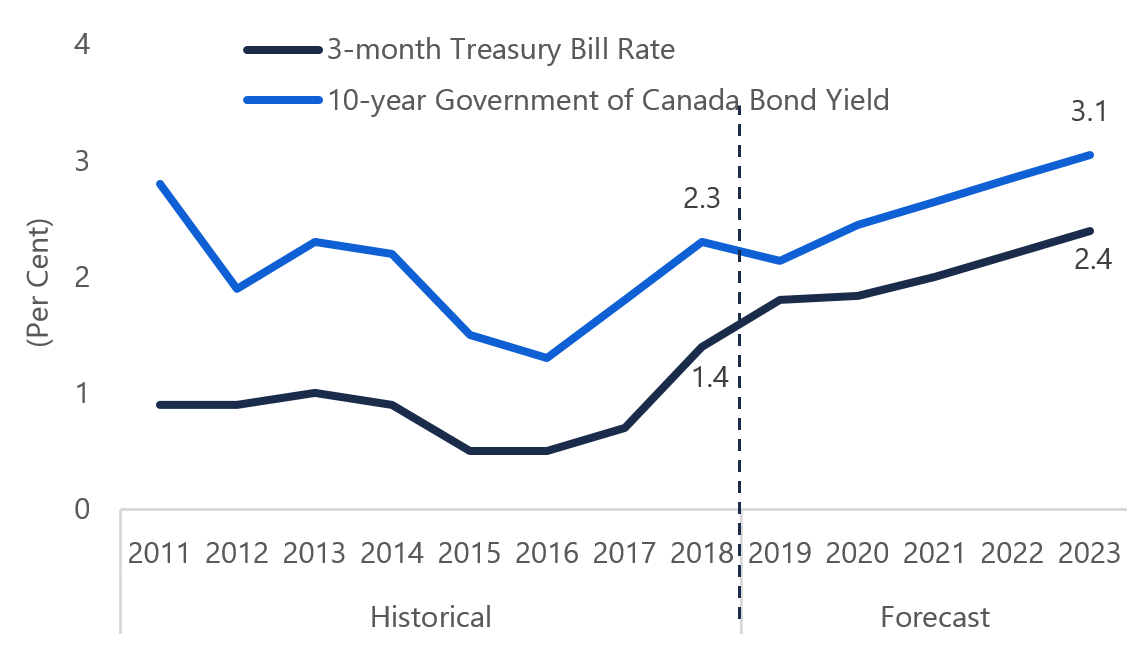

Interest rates to rise at a slower pace

The Bank of Canada has not adjusted its policy interest rate[15] since October 2018 when it raised the rate by 25 basis points to 1.75 per cent. In its most recent Monetary Policy Report, the Bank shifted its focus from the pace of future rate increases and instead emphasized the need to maintain an ‘accommodative’ policy interest rate.[16] The Bank also expects CPI inflation to return to about 2 per cent, the mid-point of the Bank’s target range, following a temporary moderation in early 2019.

Interest rate increases to pause until 2021

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

Based on the updated policy positions of both the Bank of Canada and the US Federal Reserve, the FAO now anticipates a slower rise in interest rates over the outlook than was the case in the FAO’s fall projection.

Ontario’s economic growth has slowed

Ontario real GDP grew 2.2 per cent in 2018, down from average annual gains of 2.5 per cent between 2014 and 2017. While growth in the first half of 2018 was steady, weakness in residential construction, business investment and exports in the later half of the year held back overall growth in 2018.

Economic indicators in early 2019 have also been mixed, suggesting that weaker growth in late 2018 is carrying over into 2019.[17] Interest rate increases in 2018 are also expected to contribute to more moderate growth in consumer spending this year.

In addition, based on the 2019 budget, the Ontario government plans to significantly restrain program spending increases to less than one-quarter of the pace of the last five years. As the provincial government accounts for almost half of total government spending in Ontario, slower increases in government spending will also contribute to more moderate economic growth over the outlook.[18]

These developments have led to a downward revision in the FAO’s outlook for Ontario GDP growth when compared to the fall projection. Ontario’s real GDP is now expected to grow by 1.4 per cent in 2019. Over the outlook, the FAO projects annual real GDP growth to average 1.6 per cent, reflecting moderate gains in consumer spending and residential investment, and solid contributions from exports and business investment.

| Ontario’s economic outlook has weakened | Household and government spending expected to hold back overall growth |

|

|

| Note: The FAO’s current outlook extends to 2023 but is displayed here to 2022 for comparison. | Source: Statistics Canada, Ontario Economic Accounts and FAO. |

| Accessible version | Accessible version |

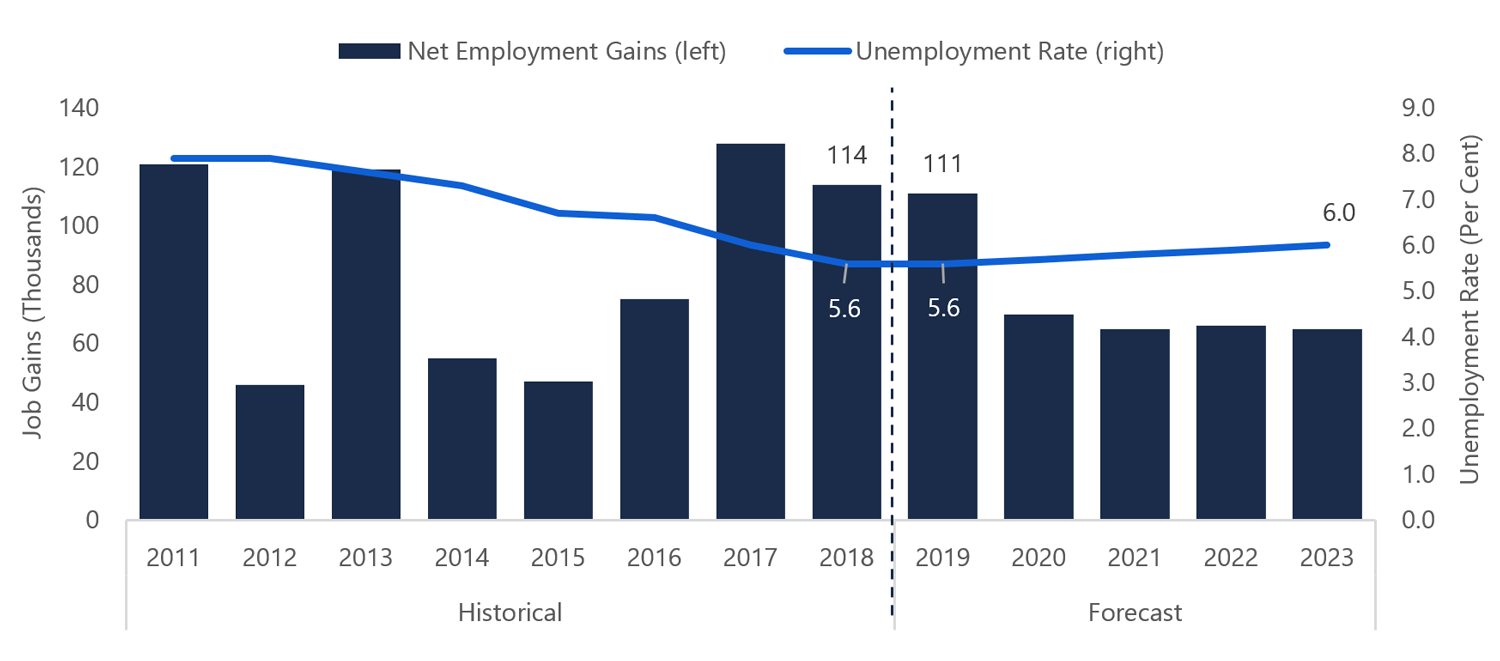

Steady Employment Gains Over Outlook

Ontario’s labour market performed very strongly in 2018 with the creation of 114,000 net new jobs and a decline in the annual unemployment rate to 5.6 per cent, the lowest since 1989. Ontario’s labour force also grew strongly last year, supported by a 1.7 per cent increase in total population, the largest annual gain since 2001. Over the outlook, annual employment gains are expected to average 1.0 per cent, in-line with growth in the labour force, keeping the unemployment rate relatively stable.

Ongoing job gains hold unemployment rate steady

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

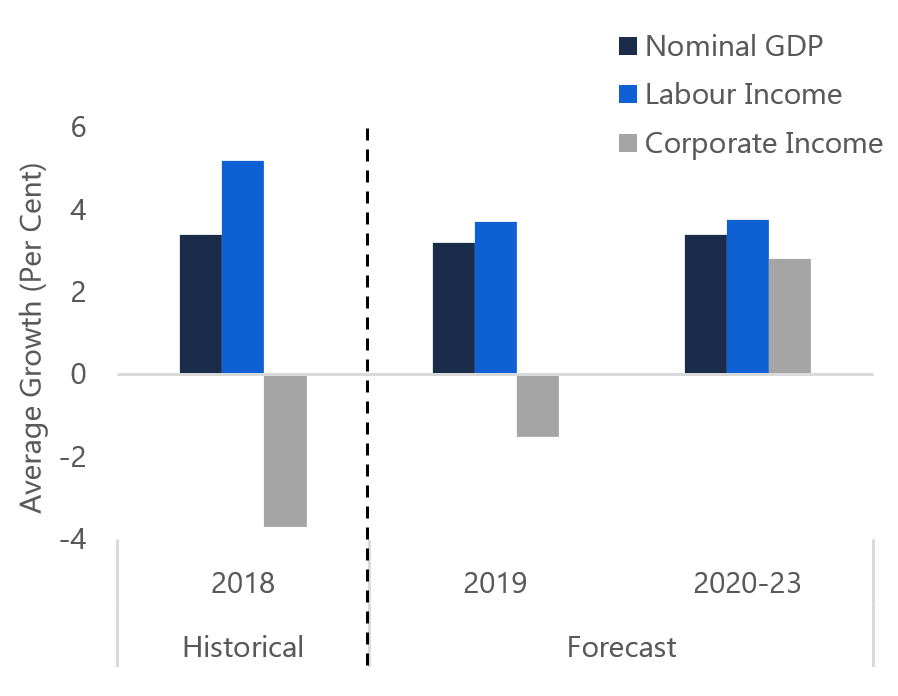

Economy-wide incomes to slow

Labour income in Ontario increased by a robust 5.2 per cent in 2018, marking the second consecutive year of strong growth amid a tight labour market. In contrast, corporate profits fell by 3.7 per cent in 2018, in part a reflection of a sharp fourth quarter profit decline. Overall, nominal GDP grew by 3.4 per cent in 2018.

Over the outlook, corporate profits are expected to recover steadily, while labour income gains are projected to moderate. Nominal GDP growth is projected to average 3.4 per cent over the outlook.

Labour income growth to slow

Source: Statistics Canada, Ontario Economic Accounts and FAO.

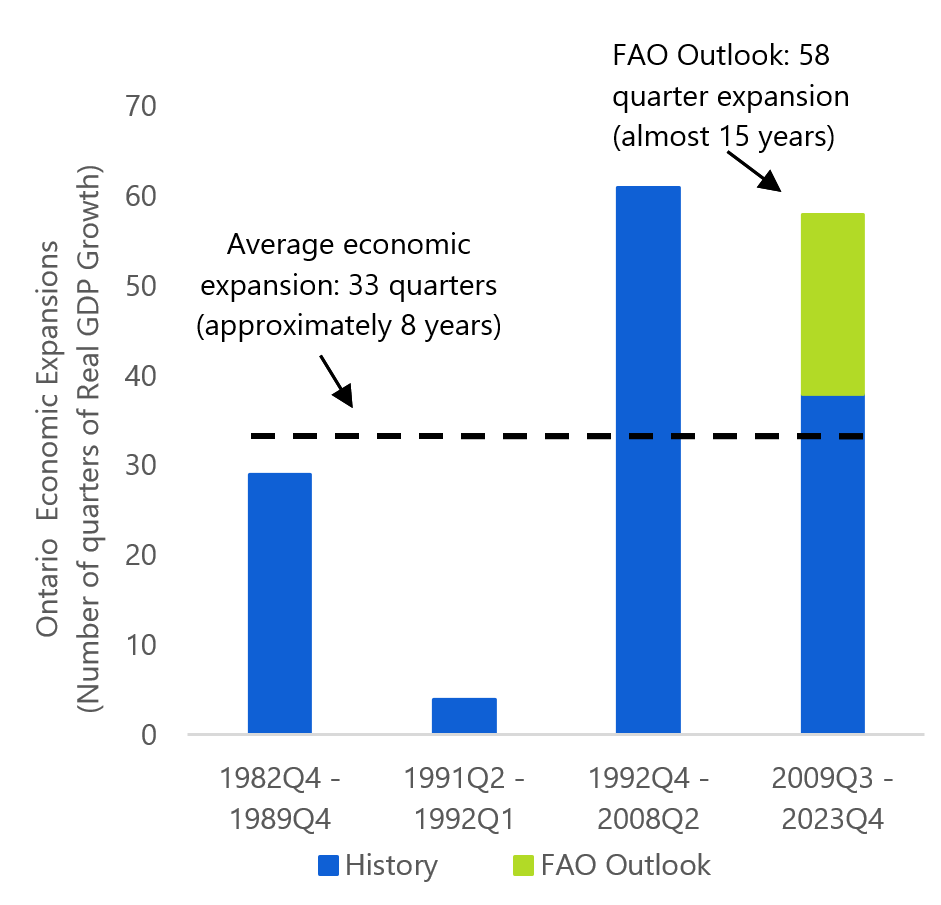

Key Risks

Ontario’s economy has recorded largely uninterrupted quarterly growth in real GDP since the global recession of 2008-2009 – a period already exceeding 9 years. As a result, the FAO’s current outlook for moderate but steady growth over the next five years implies that the current period of economic expansion will extend to match and possibly surpass the longest on record since 1981.[19]

Ontario’s current economic expansion already longer than average

Source: Statistics Canada, Ontario Economic Accounts and FAO.

While the FAO is not projecting a recession, the probability of an economic downturn has increased due to a number of significant domestic and foreign risks. These risks include a more pronounced downturn in Ontario consumer spending and residential investment weighed down by elevated household debt, and an uncertain trade, investment and political climate that could lead to a sharp deterioration in global economic growth and a decline in business activity in Ontario.

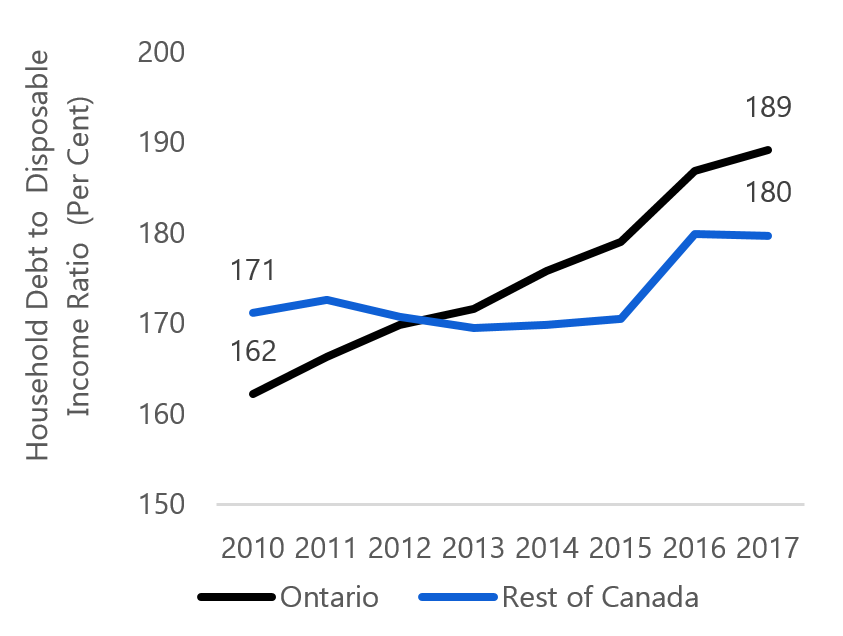

Consumer spending and household debt

Total household debt in Ontario was equivalent to 189 per cent of disposable income in 2017, significantly higher than the rest of Canada's average of 180 per cent.[20] Since 2010, the debt-to-income ratio in Ontario rose at a faster pace than in the rest of Canada, as Ontarians took on additional debt to invest in housing.[21]

Household debt-to-income ratio continues to rise in Ontario

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

Although interest rates are expected to rise only moderately over the outlook, Ontario households are already facing higher interest payments compared to their income.[22] Going forward, moderate wage growth combined with higher household interest payments will likely force households to scale back other discretionary spending, leading to weaker growth in household consumption and residential investment. A steeper-than-expected rise in interest rates or a more pronounced response by households to scale back spending could have a negative impact on overall economic growth.

An uncertain trade and investment climate

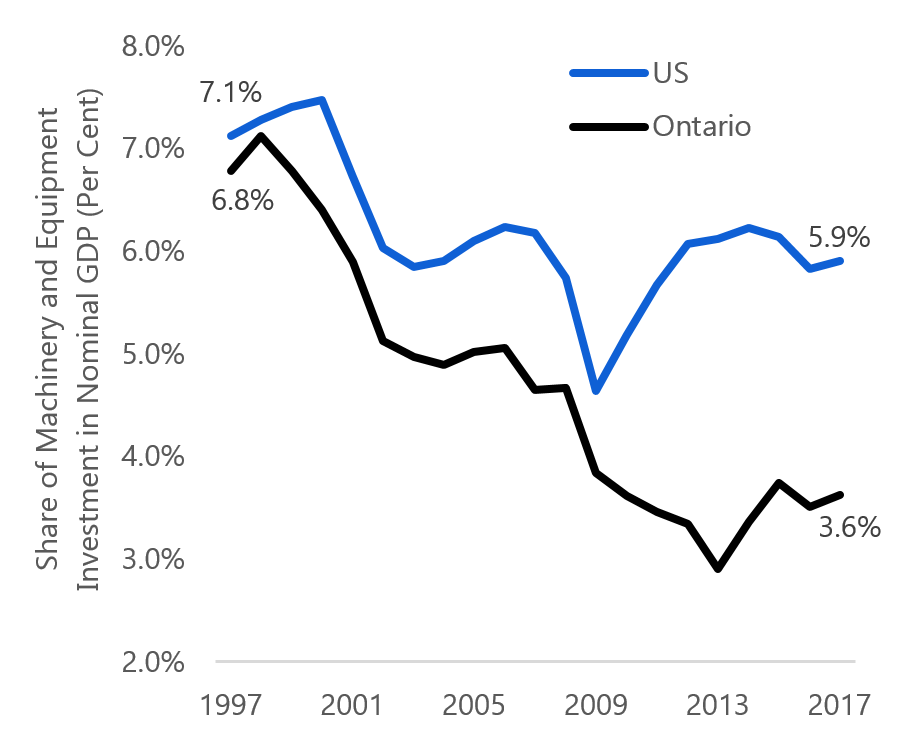

Business investment in Ontario is required to increase capacity, boost competitiveness and allow for stronger export growth. However, over the last 20 years, investment in machinery and equipment in Ontario has declined significantly as a share of the economy. In 2018, machinery and equipment investment in Ontario as a share of the overall economy was about a third lower than in the United States.

The share of machinery and equipment investment in Ontario’s economy has declined

Source: Statistics Canada, Ontario Economic Accounts, US Bureau of Economic Analysis and FAO.

Going forward, an uncertain business environment could further hold back investment in Ontario. In particular, uncertainty in global trading relationships combined with a decline in relative competitiveness due to recent US tax cuts continue to weigh on business investment in Ontario.[23]

Despite the signing of the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) last fall, the agreement still requires ratification by all three countries. However, US ratification of the agreement appears increasingly unlikely before the 2020 US presidential election. The potential for additional US demands could hold back business investment in Ontario until the final deal becomes law.

The fate of US tariffs on Canadian steel, aluminum and softwood lumber also remains unclear. Little progress has been made in talks to remove the tariffs, opening the possibility of Canada increasing its retaliatory response to the tariffs.[24] While these tariffs are unlikely to have had a material impact on Ontario’s overall economic growth, they contribute to an uncertain business environment, discouraging investment.

At the same time, weaker growth in the Chinese economy and the ongoing trade conflict between the US and China continue to present major headwinds for the global economy. Ontario’s direct exports to China may be limited, but Ontario’s economy would be affected by a more significant-than-anticipated downturn in the global economy, sparked by US-China trade tensions.

3 | Fiscal Outlook

Overview

The FAO projects Ontario’s budget deficit will decrease from $11.7 billion in 2018-19 to $10.8 billion in 2019-20 and $7.3 billion in 2020-21, reflecting modest growth in revenues and the government’s commitment to ongoing spending restraint. Under the FAO’s baseline projection,[25] Ontario’s budget balance would continue to improve rapidly over the following three years, reaching balance in 2022-23 and a relatively large surplus of $6.4 billion by 2023-24. This dramatic improvement in the budget balance over the next five years is driven primarily by the government’s plan to significantly restrain the growth in program spending.

In contrast, the 2019 Ontario Budget projects smaller deficits over the next two years due to the government’s more optimistic outlook for economic growth and revenues. Importantly, the budget’s fiscal plan incorporates provisions for unannounced measures beginning in 2021-22, which result in higher deficits and delay the achievement of a balanced budget to 2023-24.

FAO projects a balanced budget by 2022-23 excluding unannounced policies from the 2019 budget

Note: Budget balance is presented before the reserve.

Source: Ontario Public Accounts, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

To reduce the growth in program spending, the 2019 budget introduced a broad range of policy changes including: reforming OHIP+, increasing class sizes, reforming social assistance and creating an integrated supply chain model for public sector procurement. The government projected that its policy actions would deliver “savings or cost avoidance” equal to about 8 per cent, on average, of program spending each year over the next five years.[26] However, after a detailed review of the spending policy changes included in the 2019 budget, the FAO’s analysis suggests that significant additional cost reduction measures would need to be identified to achieve the program spending restraint assumed in the budget.

Revenue Outlook

Based on the FAO’s projection, Ontario’s total revenues are expected to remain largely unchanged in 2018-19, following a 7.0 per cent jump in 2017-18.[27] For 2019-20, the FAO projects a modest 1.1 per cent increase in revenue, reflecting relatively slow economic growth combined with the on-going impact of recent tax policy changes.

Over the next five years, the FAO projects total revenue growth to remain subdued, averaging just 3.2 per cent, significantly below average gains of 4.2 per cent from 2013-14 to 2018-19.

Revenue growth expected to moderate over the outlook

Source: Ontario Public Accounts, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

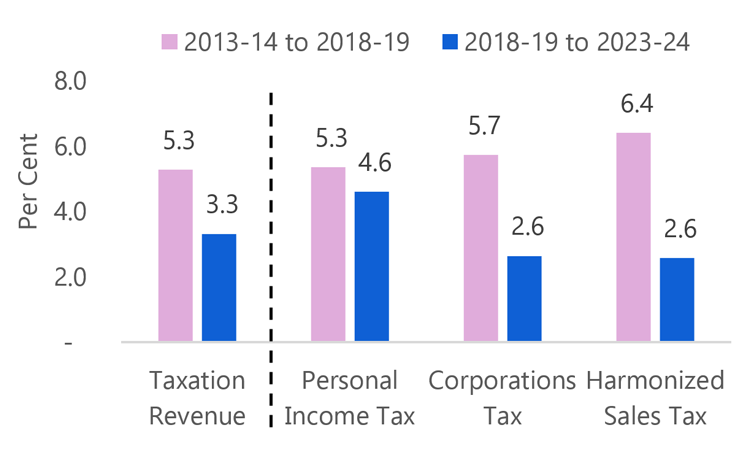

Growth in tax revenues expected to moderate

After several years of strong economic gains, slower growth over the outlook is expected to dampen revenue increases, particularly from tax sources. Over the next five years, the FAO projects average tax revenue growth of just 3.3 per cent, markedly slower than the 5.3 per cent rate from 2013-14 to 2018-19. Slower growth is projected across all three major tax categories.

Slowing economic growth to dampen revenue gains

Source: Ontario Public Accounts, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

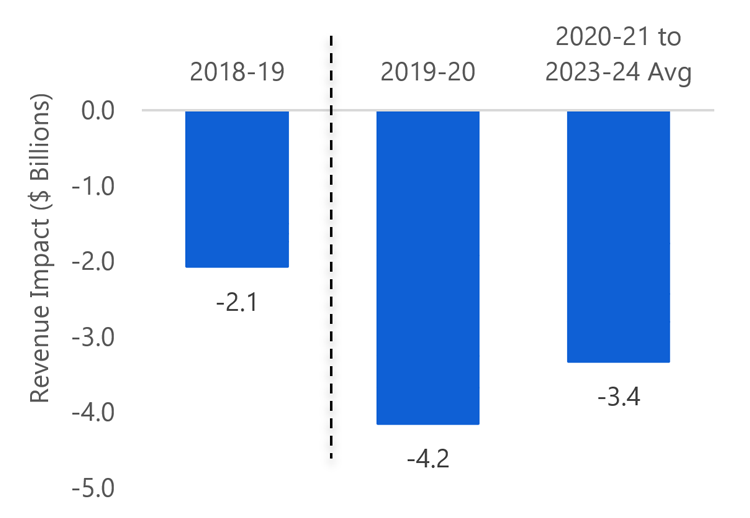

The impact of slower economic growth on revenues is compounded by recent policy measures announced since the 2018 Budget. In total, these measures will reduce revenue by $4.2 billion in 2019-20 and by an average of $3.4 billion over the remainder of the outlook.

These revenue policy changes include cancelling the cap and trade program,[28] reversing a number of tax measures included in the 2018 budget,[29] introducing the Low-income Individuals and Families Tax (LIFT) credit and paralleling federal changes to the corporate income tax.[30]

Lower revenues due to announced policy changes since the 2018 Budget

Source: FAO.

Comparison with the 2019 budget’s revenue outlook

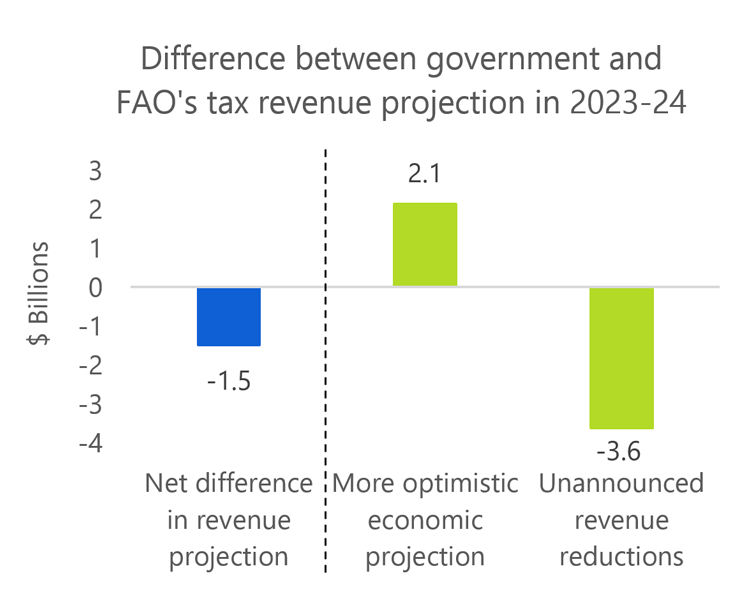

In the 2019 budget, the government projected total revenue would reach $175.1 billion by 2023-24, about $1.2 billion lower than the FAO’s projection.

In particular, the government projects taxation revenue to be $1.5 billion[31] lower than the FAO, reflecting two significant offsetting factors.

The first factor is the government’s more optimistic economic forecast, which would be expected to result in higher tax revenue. By 2023-24, Ontario nominal GDP is forecast to be approximately 0.8 per cent higher in the 2019 budget’s economic outlook compared to the FAO’s projection. This stronger economic growth would be expected to result in about $2.1 billion in higher tax revenue.

2019 Ontario Budget includes more optimistic tax revenue growth and unannounced revenue measures

Source: FAO.

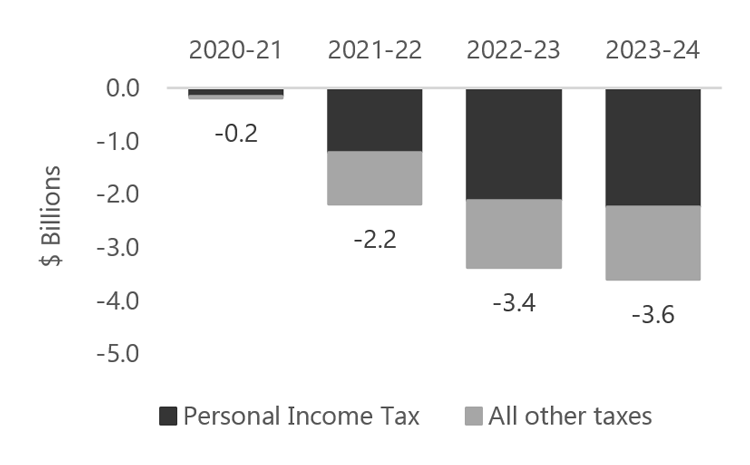

Revenue Impact of Unannounced Tax Policy Changes

Source: FAO.

However, despite the government’s stronger economic forecast, the 2019 budget included a lower projection for tax revenues relative to the FAO. The budget’s lower tax revenue forecast suggests that the government has incorporated provisions for future unannounced tax policy changes that would lead to lower revenues.[32] While the 2019 budget did not provide details on design or implementation, the FAO estimates that future unannounced tax policy changes, assumed in the government’s forecast, would reduce revenue by $0.2 billion in 2020-21, growing to $3.6 billion by 2023-24.[33]

Importantly, the FAO’s baseline revenue projections reflect existing and announced policies without assuming any implied future measures. As a result, despite an outlook for somewhat weaker economic growth, the FAO projects tax revenue would be $1.5 billion higher than the government’s budget projection by 2023-24.

FAO Medium-term Revenue Assumptions

|

Revenue Source |

Assumption |

Forecast |

|---|---|---|

|

Taxation Revenue |

Grows with key economic drivers including labour income, corporate net income, household spending and GDP. Incorporates announced policy changes, including the Low-income Individuals and Families Tax credit. Excludes unannounced policy changes. |

Averages 3.3 per cent from 2018-19 to 2023-24. |

|

Federal Transfers |

Based on legislated growth rates and economic forecasts for Ontario and Canada. |

Averages 2.7 per cent from 2018-19 to 2023-24. |

|

Government Business Enterprises (GBE) |

Based on government projections from the 2019 Budget. |

Averages 8.2 per cent from 2018-19 to 2023-24.* |

|

Other Revenue |

Based on government projections from the 2019 Budget. |

Decreases from $19.9 billion in 2017-18 to $16.8 billion in 2019-20, then rises to $18.6 billion by 2023-24. |

* The relatively strong growth rate of GBE revenue over the outlook is partially due to a one-time regulatory charge which lowers Hydro One net income in 2018-19. Excluding this regulatory charge, GBE revenue growth averages 6.5 per cent per year. See page 267 of the 2019 budget.

Source: Ontario Public Accounts, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

Expense Outlook

Based on the 2019 Ontario Budget, total government spending is projected to grow by 1.3 per cent per year on average from 2018-19 to 2023-24. The government’s spending projection assumes annual average growth in program spending of just 1.0 per cent,[34] combined with relatively rapid growth in interest on debt payments of 4.4 per cent per year.

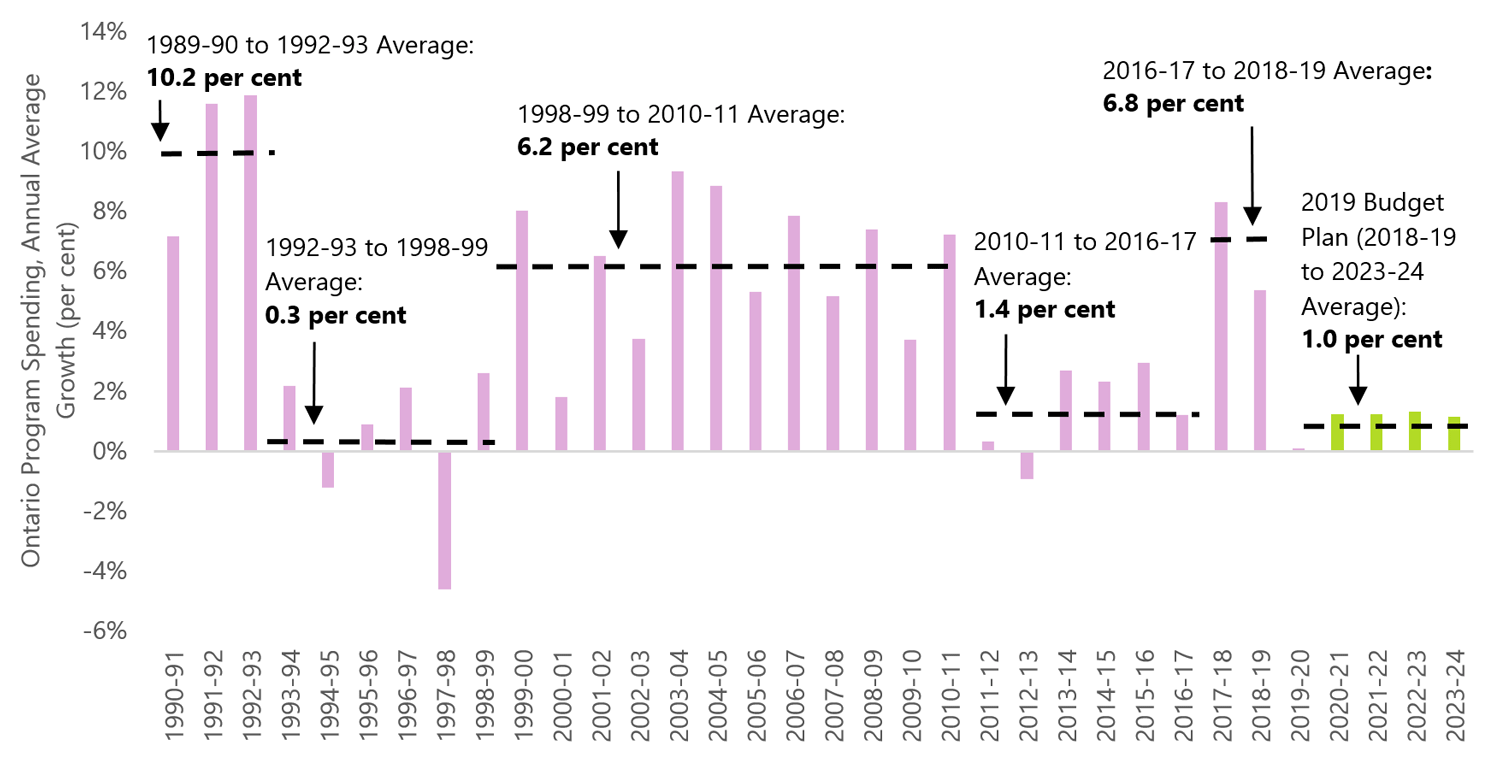

Significantly, the government’s plan to limit program spending growth to an annual average of just 1.0 per cent over the outlook would be the slowest pace of growth since the mid-1990s.

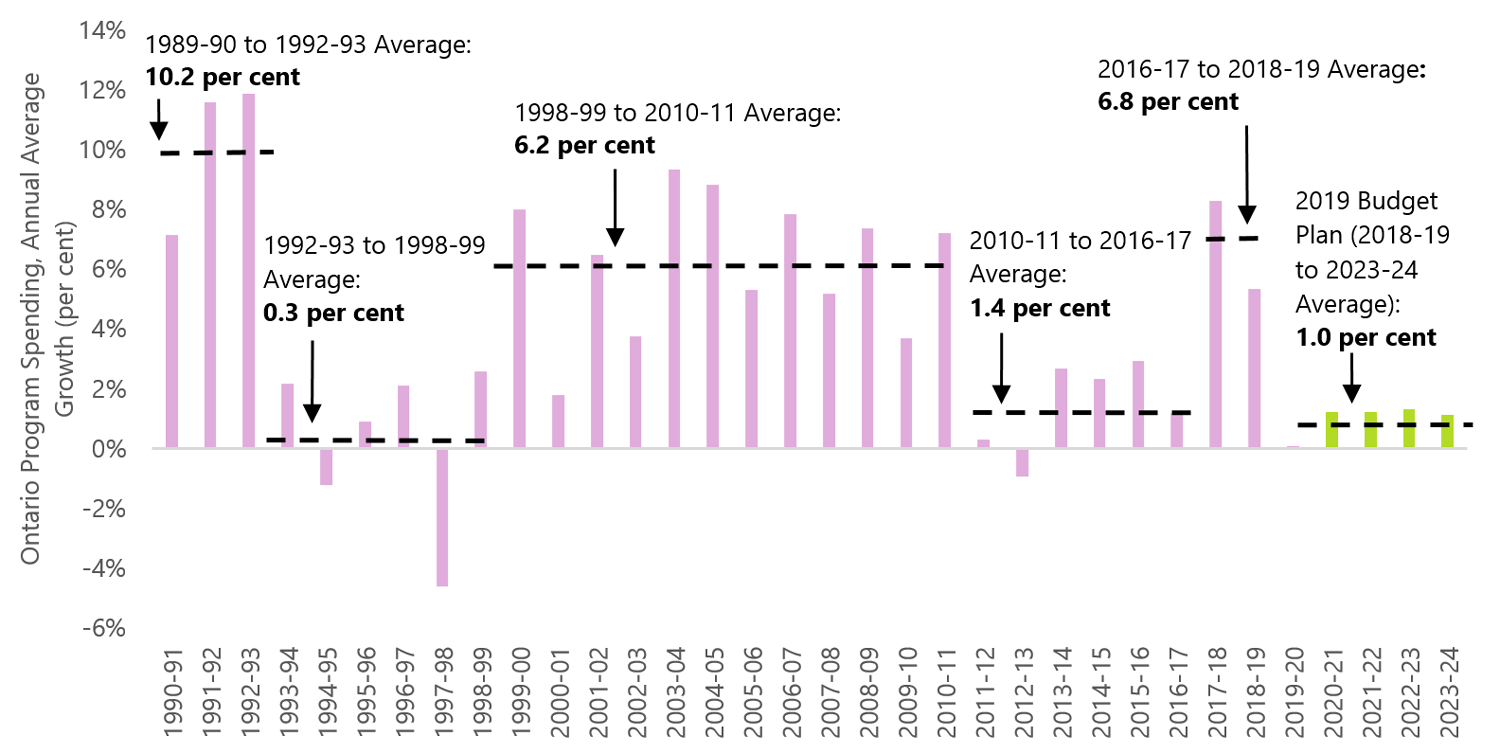

Spending growth in the 2019 budget would be the slowest since the 1990s

Note: Pre-2009 data is from Statistics Canada table 385-0001.

Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

(See appendix A1 for a discussion of program spending over the past 30 years.)

Achieving the 2019 budget’s spending plan will be a significant challenge

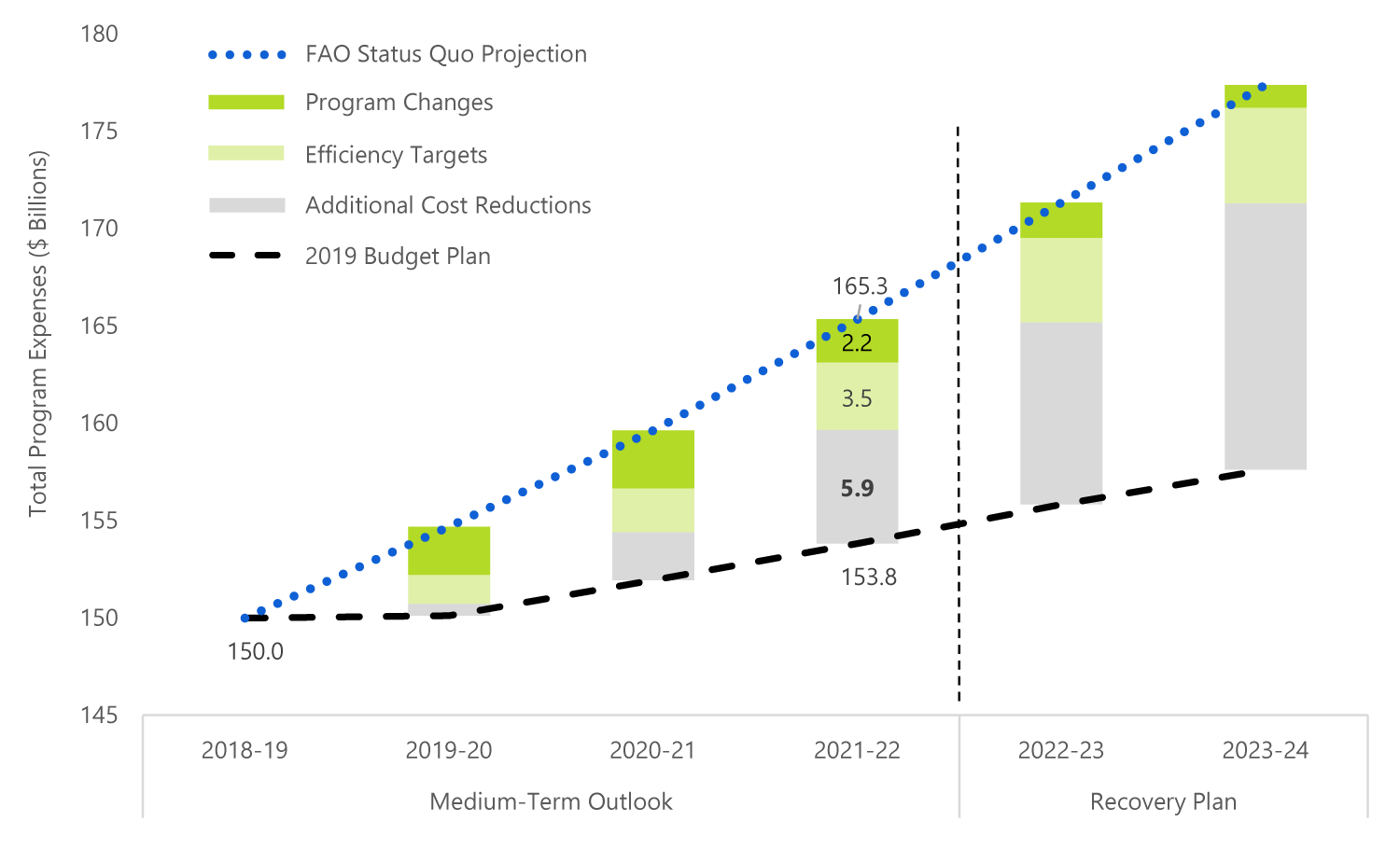

In the 2019 Ontario Budget, the government projected that its policy actions would deliver “savings or cost avoidance” equal to about 8 per cent, on average, of total program spending over the next five years.[35] The government based this statement on a comparison of the 2019 budget’s forecast for program spending with a “status quo” projection that reflects the expected future cost of providing government services consistent with the 2018 Ontario Budget.[36] Overall, the government expects that the policies reflected in the 2019 Ontario Budget will achieve “savings or cost avoidance” of about 8 per cent on average over the next five years.

Consistent with this approach, the FAO developed an independent “status quo” projection for program spending which suggests that spending would need to grow at an average rate of about 3.3 per cent over the five-year outlook, given population growth and price inflation.[37] Comparing the FAO’s status quo projection for spending with the 2019 budget’s spending projection shows a difference that is roughly equivalent, on average, to the 8 per cent in savings and cost avoidance identified in the budget.

In order to determine how the Province plans to achieve savings and cost avoidance of approximately 8 per cent, the FAO reviewed the spending policy changes included in the 2019 budget and organized the changes into two categories:

- program changes: which include changes to program entitlements, reductions or elimination of existing programs, and changes to the way existing public services are delivered (e.g. larger class sizes), and

- efficiency targets: which are measures that aim to improve the efficiency of public service delivery without impacting service access or quality.

After accounting for the 2019 budget’s policy changes, the remaining difference between the status quo program spending projection and the spending assumed in the 2019 budget represents additional cost reductions that the FAO has not been able to identify, but would be expected to achieve the government’s program spending plan.

After accounting for the 2019 budget’s policy changes, the remaining difference between the status quo program spending projection and the spending assumed in the 2019 budget represents additional cost reductions that the FAO has not been able to identify but would be needed to achieve the government’s program spending plan.

By 2021-22, program changes and efficiency targets in the 2019 budget will account for about half of the total cost reductions needed to achieve the government’s projected cost savings

Source: FAO analysis of data from TBS.

The FAO estimates that the program changes contained in the 2019 budget plan could save the Province $2.2 billion by 2021-22, if fully realized. These changes will impact many programs[38] across all areas of government and include:

- Reforming OHIP+ to cover only children and youth without pre-existing drug plans, which is projected to save at least $250 million annually beginning in 2019-20.[39]

- Increasing class sizes for students in grades 4 through 12 and expanding e-learning for secondary school students.

- Reductions to municipal transfer payments relative to the 2018 budget plan.

- Changes to reduce public funding for many other programs including the Ontario Student Assistance Program, legal aid and public health.

The 2019 budget also announced a wide range of efficiency measures which, in total, could produce an additional $3.5 billion in cost reductions by 2021-22, if fully realized. These measures include:

- Creating an integrated supply chain model to consolidate procurement practices across the Ontario Public Service and broader public sector, which the Province estimates will save $1 billion annually.[40]

- Reducing funding in the Children’s and Social Services sector by almost $1.3 billion by 2021-22.[41]

- Consolidating the Province’s 14 Local Health Integration Networks and six Provincial health agencies into one single agency, Ontario Health, which the Province estimates will result in $350 million of annual savings.[42]

- Reviewing the efficiency of school board operations.

- Transforming the delivery of children’s and social services, including social assistance, developmental services and youth justice services.

(See appendix A2 for more details of program spending changes by sector.)

For the first two years of the budget plan 2019-20 and 2020-21 – the program changes and efficiency targets identified by the FAO are largely sufficient to achieve the cost savings assumed in the government’s spending plan. But starting in 2021-22, the FAO’s analysis suggests that additional cost reductions totalling almost $6 billion (about 4 per cent of total program spending in that year) would be needed to achieve the cost savings projected in the 2019 budget. [43] This implies that significant future policy decisions will likely be needed for the Province to achieve the 2019 budget’s spending projections starting in 2021-22.

While the program changes and efficiency targets included in the 2019 budget would be expected to result in cost reductions, there is significant risk that these initiatives may not produce the cost savings anticipated in the budget plan. While transformational changes to public services that lead to permanent efficiency gains are possible, they have generally been difficult to achieve.[44]

The 2019 Budget would reduce spending per person by $1,100 by 2023-24

The 2019 budget plan to restrain program spending growth to an average annual rate of 1.0 per cent over the next five years would reduce provincial spending on goods and services per person by $1,100* by 2023-24, compared to the current level of spending.

The 2019 budget would lower per capita spending

Source: Ontario Public Accounts, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

* Expressed in 2018 dollars.

Budget Balance Outlook

The FAO projects Ontario’s budget deficit will decrease from $11.7 billion in 2018-19 to $10.8 billion in 2019-20 and $7.3 billion in 2020-21. Under the FAO’s baseline projection,[45] Ontario’s budget balance would continue to improve rapidly over the following three years, reaching balance in 2022-23 and a relatively large surplus of $6.4 billion by 2023-24. This dramatic improvement in the budget balance over the next five years is driven primarily by the government’s plan to significantly restrain the growth in program spending.

In contrast, the 2019 Ontario Budget projects smaller deficits over the next two years due to the government’s more optimistic outlook for revenue growth. Importantly, the budget’s fiscal plan also incorporates provisions for unannounced measures beginning in 2021-22, which increase the deficit and delay the achievement of a balanced budget to 2023-24.

FAO projects a balanced budget by 2022-23 excluding unannounced policies from the 2019 Budget

Source: Ontario Public Accounts, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

Note: Budget balance is presented before the reserve.

Borrowing and Net Debt

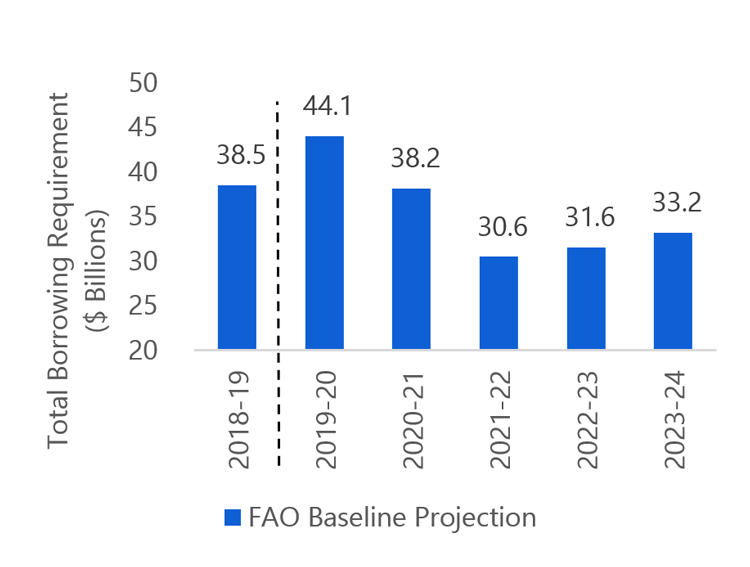

Based on the FAO’s baseline projection, which excludes the government’s unannounced measures, Ontario’s borrowing is expected to peak at $44 billion in 2019-20, before declining to approximately $30 billion beginning 2021-22.

FAO projects borrowing to decrease over the next five years

Note: ‘Total borrowing requirement’ refers to the ‘total funding requirement’ concept presented in the 2019 Budget.

Source: 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

The FAO’s current borrowing forecast is significantly lower than the FAO’s fall 2018 projection[46] primarily due to an improved outlook for the budget balance and lower government capital investment than previously planned.[47]

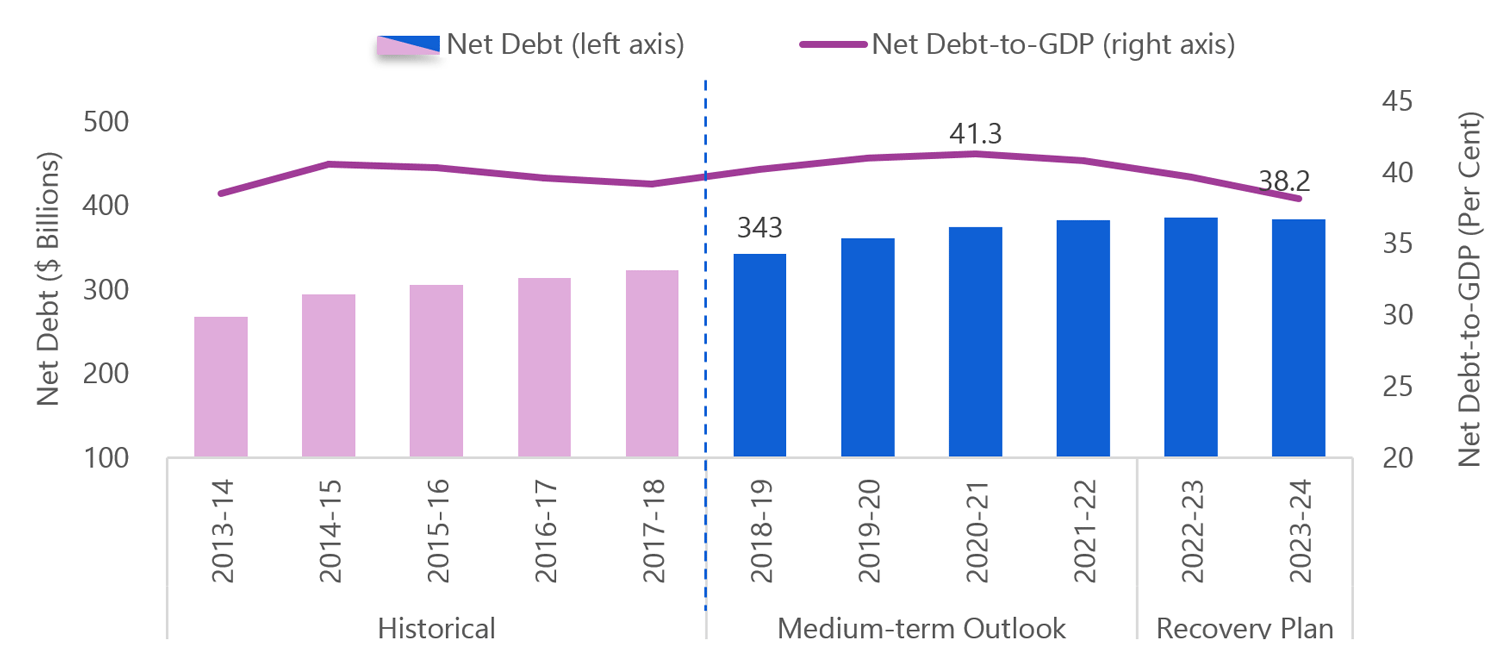

Growth in Ontario’s net debt is expected to slow over the next four years as the budget balance improves. Based on the FAO’s projection, Ontario’s net debt-to-GDP ratio would be expected to peak at 41.3 per cent in 2020-21 before falling to 38.2 per cent by 2023-24.[48]

Ontario’s net debt-to-GDP ratio to fall to 38.2 per cent in 2023-24

Source: 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

Impact of Implementing Unannounced Measures

In the FAO’s baseline projection, unannounced measures in the 2019 budget plan are excluded, as these measures are not reflected in current legislation and have not been formally proposed by the government. On this basis, the FAO projects that the Ontario budget would reach a significant $6.4 billion surplus by 2023-24, achieved primarily through spending restraint.

If the Province were to implement these unannounced measures, the FAO estimates that the budget balance would deteriorate by $2.9 billion in 2021-22, $4.7 billion in 2022-23 and by $5.5 billion by 2023-24. This would delay achieving a balanced budget by one year to 2023-24, resulting in a budget surplus of $0.9 billion in that year.

Overall, the FAO’s projection including unannounced measures is roughly consistent with the government’s projection in the 2019 budget.[49]

Impact of the 2019 Budget’s unannounced measures on budget balance, $ billions

|

2018-19 |

2019-20 |

2020-21 |

2021-22 |

2022-23 |

2023-24 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Budget Balance - FAO Baseline |

-11.7 |

-10.8 |

-7.3 |

-2.8 |

1.5 |

6.4 |

|

Impact of implementing unannounced measures* |

-0.1 |

-2.9 |

-4.7 |

-5.5 |

||

|

FAO Baseline Budget Balance |

-11.7 |

-10.8 |

-7.4 |

-5.7 |

-3.2 |

0.9 |

|

Budget Balance - 2019 Budget |

-11.7 |

-9.3 |

-5.8 |

-4.6 |

-2.2 |

1.9 |

Note: Budget balance is presented before the reserve.

*Values include the impact to interest on debt payments.

Source: 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

The FAO’s baseline projection (excluding unannounced measures) suggests that by restraining program spending growth, the government is creating “fiscal room” while still achieving a balanced budget by 2023-24. Based on the FAO’s projection, implementing the government’s unannounced measures would completely fill the available fiscal room, but still result in a small budget surplus of $0.9 billion in 2023-24.

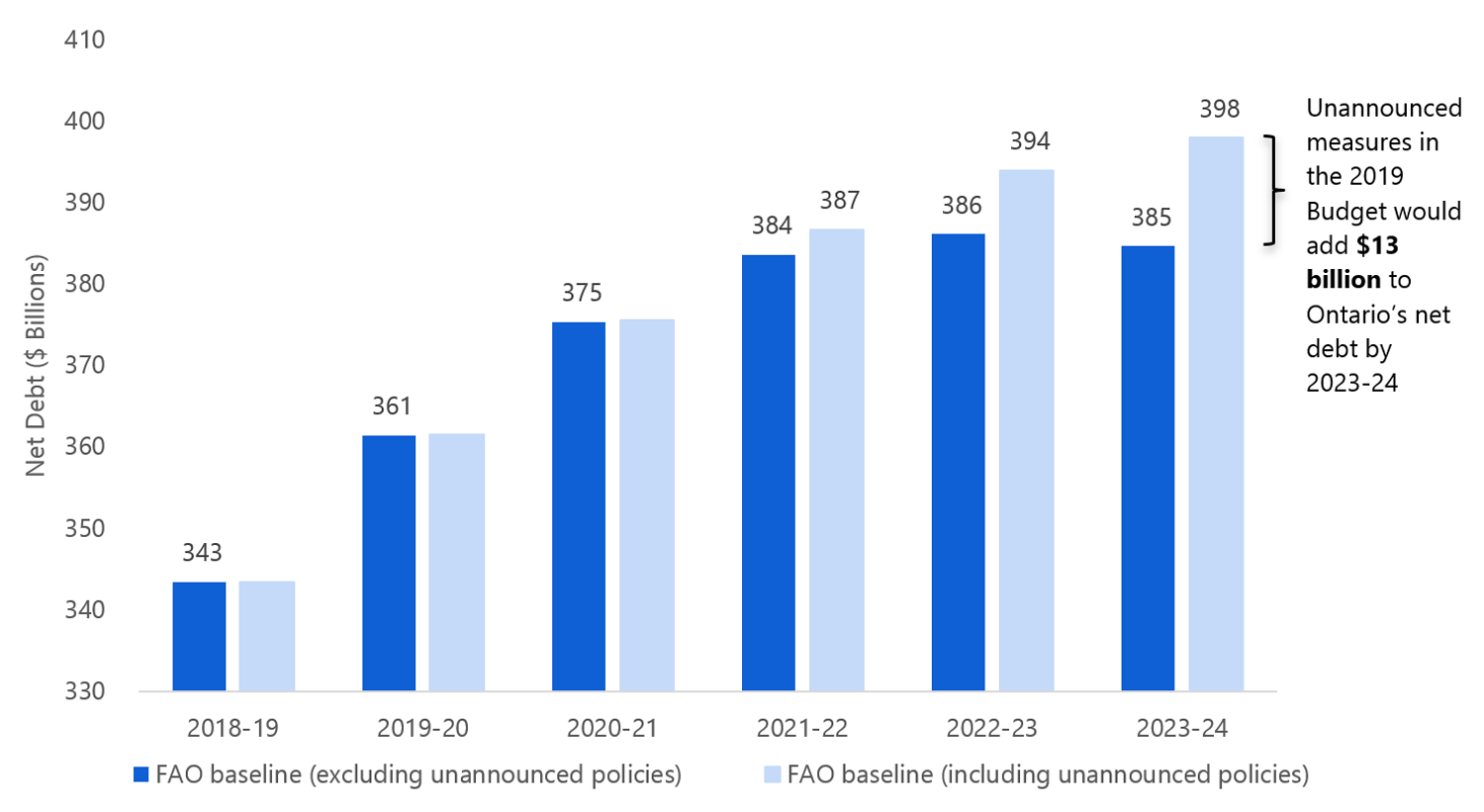

However, implementing the government’s unannounced measures would also delay the achievement of a balanced budget by one year (from 2022-23 to 2023-24) and result in an additional $13 billion in net debt by 2023-24. Alternatively, the government could raise program spending growth from 1.0 per cent per year, as projected in the 2019 Budget, to 1.4 per cent[50] per year and still achieve a balanced budget by 2023-24.[51]

Unannounced measures in the 2019 Budget would add $13 billion to Ontario’s net debt by 2023-24

Source: 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

Budget Sensitivities

Changes in Ontario’s current revenue or expense policies, as well as external factors, can have a significant impact on Ontario’s budget balance. The FAO provides estimates of the sensitivity of Ontario’s fiscal position to potential changes across several key policy areas.

On tax policy, if the government were to permanently increase personal income tax (PIT) revenue by 10 per cent or around $500 per person, starting in 2019-20, the government’s budget deficit would fall by $3.7 billion in the first year and by $5.2 billion in 2023-24. Alternatively, if the government raised the general corporate income tax rate by one percentage point in 2019-20, the budget deficit would decrease by $1.1 billion in that year and by $1.6 billion in 2023-24. If the government were to increase the Harmonized Sales Tax rate (HST) from 8 per cent to 9 per cent in 2019-20, the budget deficit would decrease by $3.6 billion in 2019-20 and by $4.7 billion in 2023-24.

For expenditure policy, if the government were to decrease the growth rate of program spending by 0.5 percentage point for each year of the projection, the budget deficit would decrease by $4.4 billion by 2023-24. If the government were to reduce the growth rate of health expenditures by 1 percentage point for each year of the projection, the deficit would decline by $3.9 billion by 2023-24. Similarly, if the growth rate of social assistance was reduced by 1 percentage point in 2019-20, the deficit would be $0.6 billion lower by 2023-24.

If Ontario’s effective borrowing rate were to decrease by 1 percentage point in 2019-20, the deficit would decline by $0.5 billion in 2019-20 and $1.7 billion in 2023-24.

Sensitivity of Ontario’s Budget Balance to Select Factors

|

Change in budget balance in: |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Change Beginning in 2019-20 |

2019-20 |

2023-24 |

|

Tax Policy |

||

|

A sustained 10 per cent increase in Personal Income Tax revenues ($500 per tax filer in 2019-20) over the projection |

+$3.7 billion |

+$5.2 billion |

|

A sustained 1 percentage point increase in the general Corporations Tax rate over the projection |

+$1.1 billion |

+$1.6 billion |

|

A sustained 1 percentage point increase in the HST rate over the projection |

+$3.6 billion |

+$4.7 billion |

|

Federal Transfers |

||

|

A sustained 1 percentage point increase in the annual growth of the Canada Health Transfer over the projection |

+$0.2 billion |

+$1.0 billion |

|

A sustained 1 percentage point increase in the annual growth of the Canada Social Transfer over the projection |

+$0.1 billion |

+$0.4 billion |

|

Expenditure Policy |

||

|

A sustained 0.5 percentage point decrease in the growth rate of total program spending over the projection |

+$0.8 billion |

+$4.4 billion |

|

A sustained 1 percentage point decrease in the growth rate of health spending over the projection |

+$0.6 billion |

+$3.9 billion |

|

A sustained 1 percentage point decrease in the growth rate of social assistance over the projection |

+$0.1 billion |

+$0.6 billion |

|

Borrowing Costs |

||

|

A sustained 1 percentage point decrease in Ontario’s effective borrowing rate over the projection |

+$0.5 billion |

+$1.7 billion |

Note: These estimates include the associated impact to interest on debt, but do not incorporate any economic feedback effects.

4 | Appendices

A1: Program Spending in Historical Perspective

While Ontario program spending grew at an annual average rate of 4.4 per cent from 1989-90 to 2018-19, there have been periods of rapid spending growth, and periods of spending restraint. Since 1989,[52] there have been two periods of prolonged spending restraint in Ontario, similar to that being proposed in the 2019 budget. After the onset of the early-1990s recession, successive governments used a combination of strategies to limit the growth in program spending to 0.3 per cent annually from 1992-93 to 1998-99.

Periods of slow program spending growth were followed by ‘catch-up’ periods

Note: Pre-2009 data is from Statistics Canada table 385-0001.

Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

The spending restraint of the 1990s was followed by a prolonged period of above-average growth during the 2000s, when program spending grew by 6.2 per cent annually. This period of strong growth reflected the introduction of new public services but was also a response to relieve spending pressures that had built-up during the 1990s.

Starting in 2011-12, following the government’s response to the 2008-2009 recession, limiting spending growth was a critical part of the Province’s attempt to balance the budget in 2017-18. Spending restraint was achieved through a combination of strategies, including delivering public services more efficiently,[53] restraining public-sector wage growth,[54] and deferring maintenance for schools and hospitals.[55] This reduced program spending growth to an average of 1.4 per cent per year from 2010-11 to 2016-17. In 2017-18 and 2018-19, program spending increased by an average of 6.8 per cent to relieve some of the built-up spending pressure[56], and to fund the introduction of new programs. Beginning in 2019-20, the government plans to grow program spending by an average of 1.0 per cent per year over the next five years.

A2: Program Spending Changes by Sector

The FAO estimated “status quo” projections for program spending in the major government sectors of health, education and social services, and compared the FAO’s status quo projection against the Province’s 2019 budget outlook. The difference between the FAO’s status quo outlook and the Province’s budget outlook reflects the “savings and cost avoidance” noted in the 2019 budget.

In order to determine how the Province intends to achieve the 2019 budget’s program spending plan, the FAO reviewed the spending policy changes included in the budget and organized them into two categories: program changes and efficiency targets.

After accounting for the budget’s spending policy changes, the remaining difference between the status quo program spending projection and the spending assumed in the 2019 budget represents additional cost reductions that the FAO was not able to identify but would be required to achieve the government’s program spending plan.

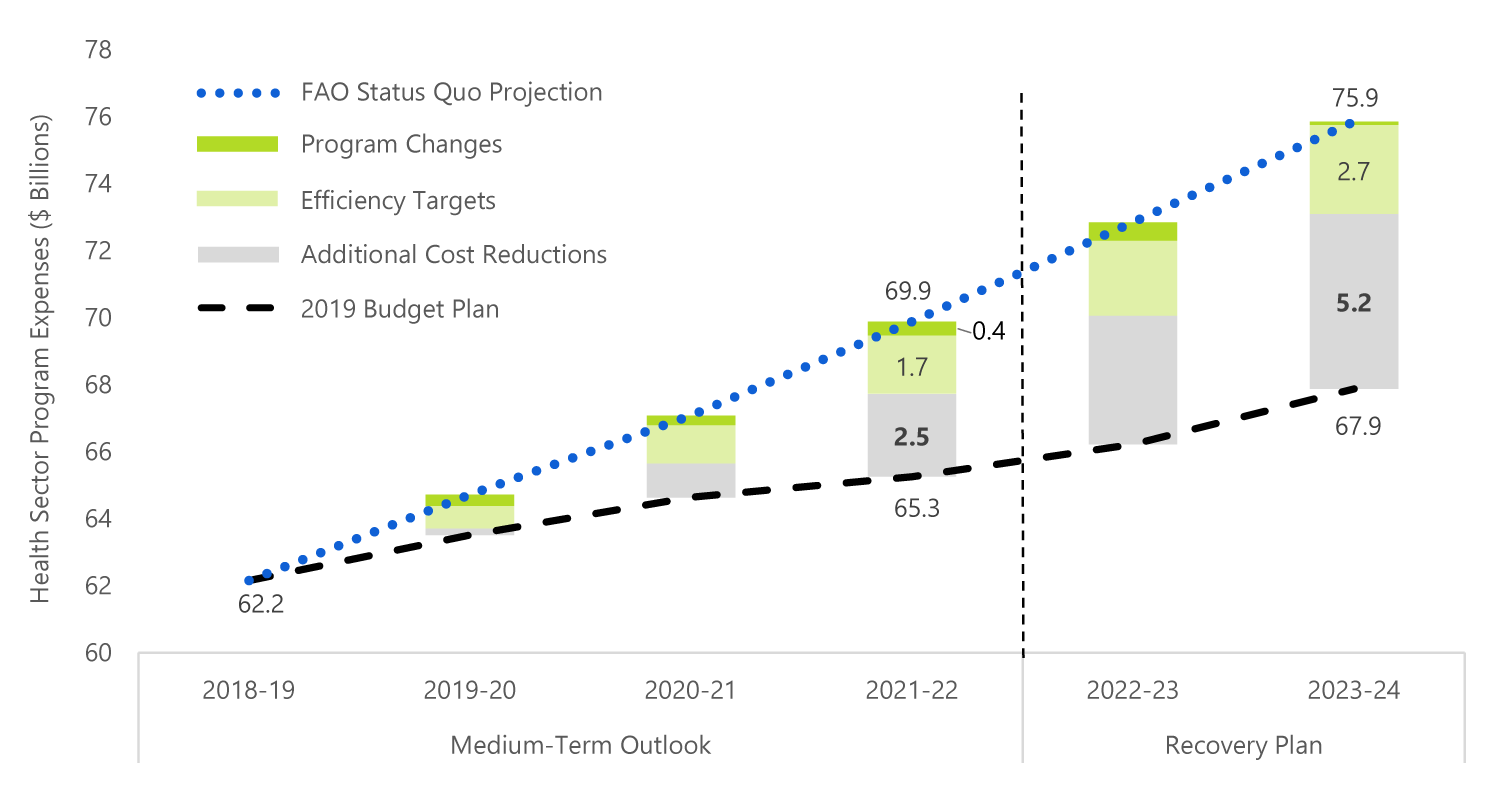

Health Sector Spending

The 2019 Ontario Budget projects that health sector expense will grow at an annual average rate of 1.8% from 2018-19 to 2023-24, increasing from $62.2 billion to $67.9 billion.

The FAO’s status quo forecast projects health spending would need to grow at an average annual rate of 4.1% from 2018-19 to 2023-24, reaching $75.9 billion in 2023-24.

By 2021-22, $2.5 billion of additional cost reductions will need to be identified in the health sector

Source: 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

The 2019 budget plan included the following program changes for health care spending:

- Reducing the number of Public health units from 35 to 10 and cutting funding by $200 million annually.[58]

- Reforming OHIP+ to only cover children and youth without pre-existing drug plans which is projected to save over $250 million annually beginning in 2019-20.[59]

However, the Province has also announced the expansion of certain health sector programs including a $1.8 billion five-year investment in long-term care and a new dental program for low-income seniors. In total, the FAO estimates that program changes in the health sector will generate $0.4 billion in net savings by 2021-22.

In addition, the 2019 budget introduced several efficiency targets for the health sector including:

- Consolidating the Province’s 14 Local Health Integration Networks and six Provincial health agencies into one single agency, Ontario Health, estimated to result in $350 million of annual savings.

- Creating an integrated supply chain model which the Province estimates will help to reduce health sector expense.

- Implementing changes to transfer payment agreements and pharmacy fee payments which the Province estimates will save $240 million annually by 2021-22.

- Adopting workforce optimization measures which the Province estimates will reduce health sector expense by $250 million by 2021-22.[60]

The FAO estimates that these efficiency measures could reduce health sector spending by $1.7 billion by 2021-22.

Taken together, the FAO estimates that the province’s proposed net program changes and efficiency targets could reduce health sector expense by a total of $2.1 billion by 2021-22. This leaves an estimated $2.5 billion in additional cost reductions in the health sector in 2021-22. By 2023-24, the additional cost reductions needed to achieve the government’s health spending projection rises to $5.2 billion.

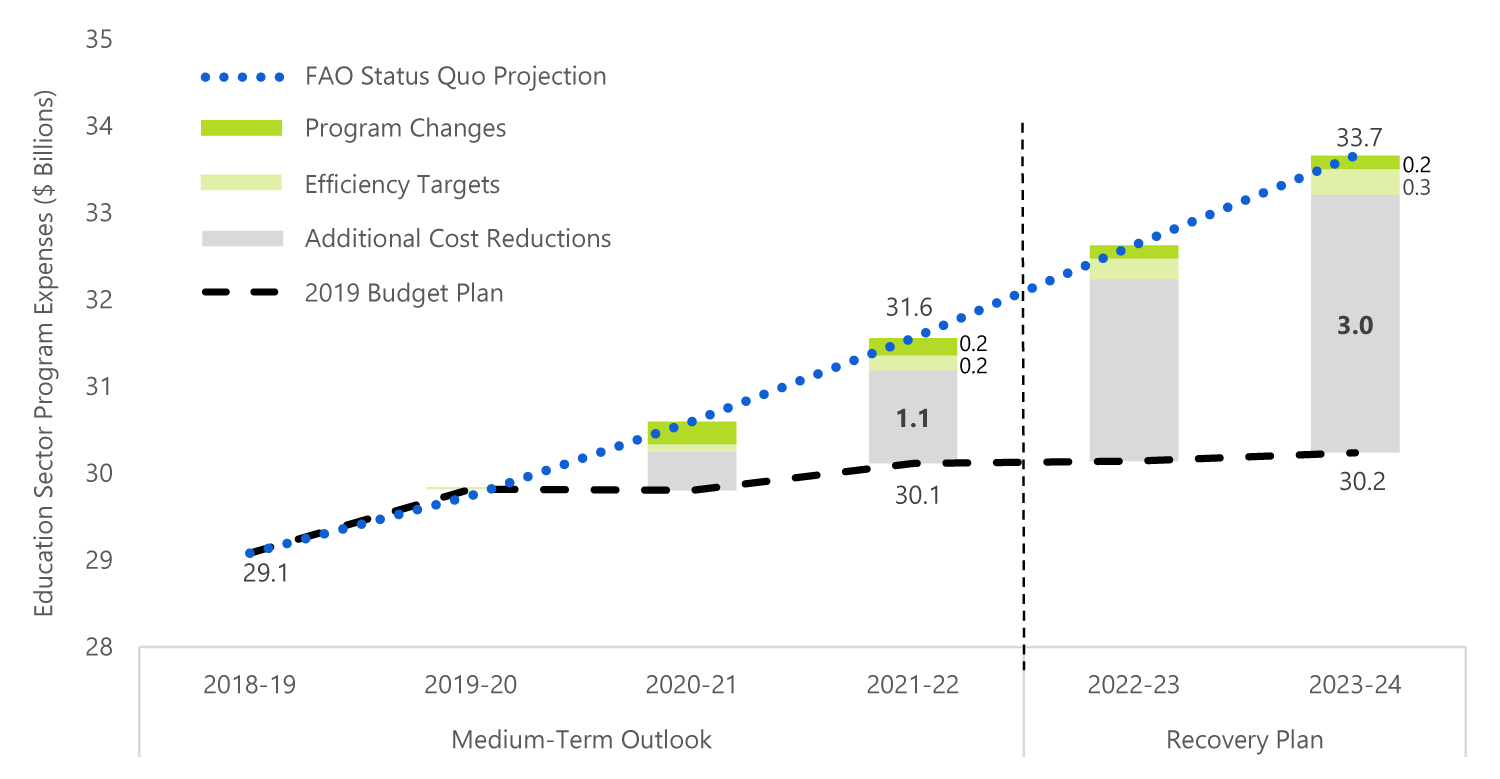

Education Sector Spending

The Province projects that education sector spending will grow at an average annual rate of 0.8 per cent between 2018-19 and 2023-24, increasing from $29.1 billion in 2018-19 to $30.2 billion by 2023-24.

Based on the FAO’s status quo forecast, education sector spending would need to grow at an average annual rate of 3.0 per cent over the same period, reaching $33.7 billion by 2023-24.

By 2021-22, $1.1 billion of additional cost reductions will need to be identified in the education sector

Source: Ontario Public Accounts, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

Announced savings from education sector program changes and efficiency targets include:

- Increasing class sizes for students in grades four through twelve.

- Expanding e-learning for secondary students. [61]

In total, efficiency measures and net program changes in the education sector are expected to result in savings of $0.4 billion by 2021-22, with $1.1 billion in additional cost reductions yet to be identified. By 2023-24, the additional cost savings needed to achieve the government’s education spending plan rise to $3.0 billion.

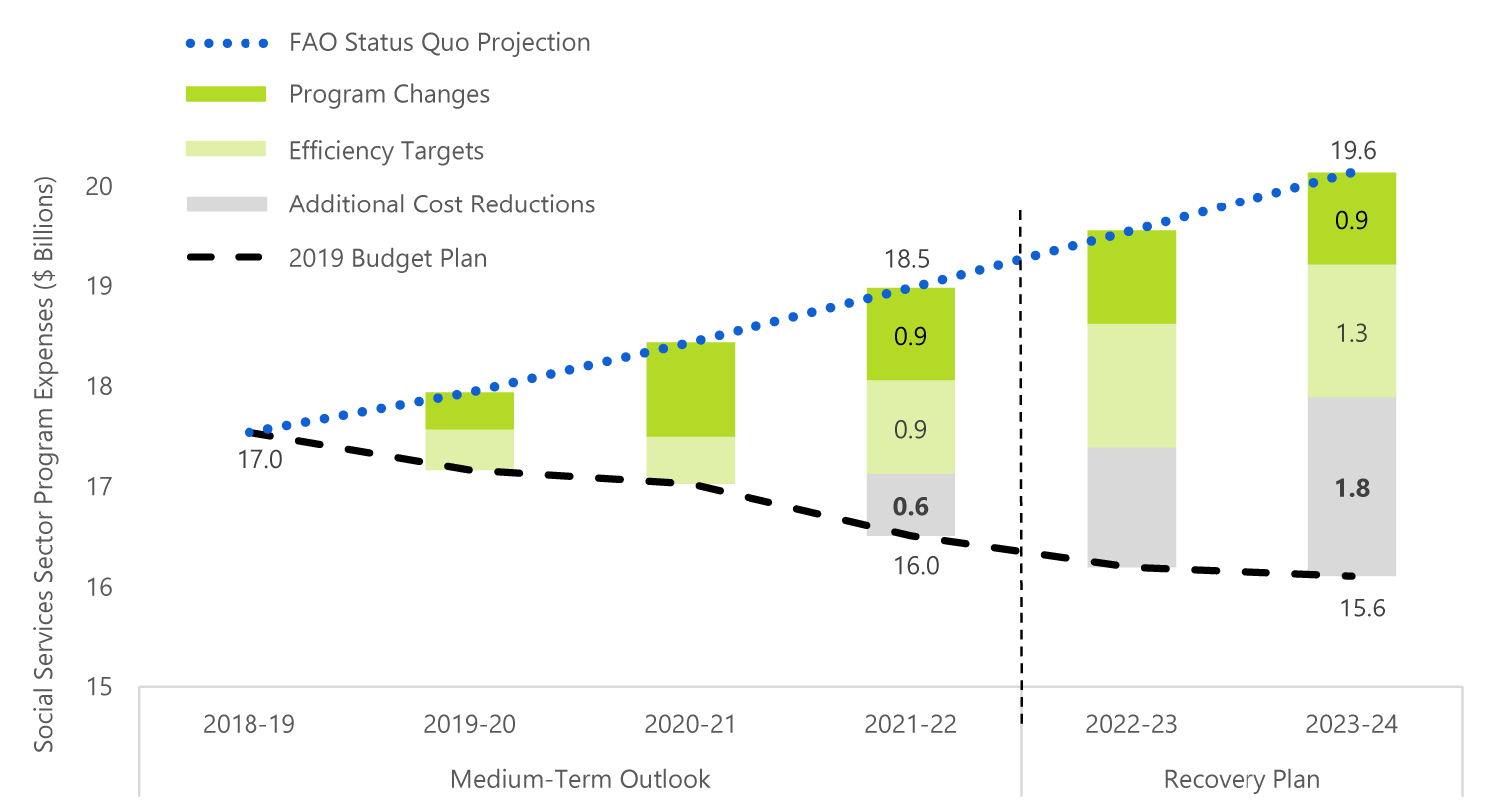

Children’s and Social Services Sector Spending

The 2019 Ontario Budget projects a decrease in spending in the children's and social services sector from $17.0 billion in 2018-19 to $15.6 billion by 2023-24 – a 1.7 per cent annual average decrease.

The FAO’s status quo projection estimates spending in social services would need to increase by about $2.6 billion to $19.6 billion by 2023-24 – an annual average increase of 2.9 per cent – to fund rising demographic demand and price inflation.

By 2021-22, $0.6 billion of additional cost reductions will need to be identified in the children’s and social services sector

Source: Ontario Public Accounts, 2019 Ontario Budget and FAO.

The 2019 budget outlined several major policies (program changes and efficiency targets) for children’s and social services sector programs, notably:

- Social assistance reform (estimated annual savings of $720 million by 2021-22);

- Modernization of youth justice services (estimated annual savings of $48 million by 2021-22);[62] and

- Other major sector-wide operational efficiencies and cost-savings (estimated annual savings of $510 million by 2021-22).

In total, the FAO identified efficiency targets of $0.9 billion and net program changes of $0.9 billion, resulting in expected savings of $1.8 billion by 2021-22, with $0.6 billion in additional cost reductions yet to be identified. By 2023-24, the additional cost savings needed to achieve the government’s spending plan in the children’s and social services sector rises to $1.8 billion.

A3: Forecast Tables

Table 1a: FAO Outlook for Key Revenue Drivers

|

(Per Cent Growth) |

2017a |

2018a |

2019f |

2020f |

2021f |

2022f |

2023f |

Average* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nominal GDP |

||||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

4.1 |

3.4 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

4.1 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

3.2 |

3.6 |

3.9 |

3.5 |

|

Consensus ** |

4.1 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

3.7 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

4.0 |

3.7 |

|

Labour Income |

||||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

4.7 |

5.2 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

3.7 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

4.7 |

5.2 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

4.0 |

4.1 |

3.9 |

|

Corporate Profits |

||||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

1.8 |

-3.7 |

-1.5 |

1.2 |

3.0 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

2.0 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

1.8 |

-3.7 |

4.4 |

1.2 |

2.9 |

3.7 |

4.5 |

3.3 |

|

Household Consumption |

||||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

5.1 |

4.7 |

3.3 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.5 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

a = Actual f = Forecast

* Average is calculated from 2019 to 2023.

** See 2019 Ontario Budget page 245 for list of consensus forecasters. Forecasts as of April 26th, 2019.

Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Ontario Budget, Ontario Economic Accounts, Ontario Ministry of Finance and FAO.

Table 1b: FAO Outlook for Ontario Real GDP and Components

|

(Per Cent Growth) |

2017a |

2018a |

2019f |

2020f |

2021f |

2022f |

2023f |

Average* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Real GDP |

||||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

2.8 |

2.2 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

2.8 |

2.2 |

1.4 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

|

Consensus ** |

2.8 |

2.2 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

1.8 |

|

Real GDP Components |

||||||||

|

Household Consumption |

3.9 |

2.8 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

|

Residential Investment |

1.0 |

-4.7 |

-3.1 |

1.3 |

1.9 |

2.3 |

2.5 |

1.0 |

|

Business Investment *** |

4.8 |

2.8 |

0.3 |

3.3 |

2.9 |

2.5 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

|

Government (Consumption and Investment) |

2.6 |

2.9 |

-0.2 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

|

Exports |

1.8 |

2.3 |

1.7 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

1.9 |

|

Imports |

5.1 |

1.7 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

a = Actual f = Forecast

* Average is calculated from 2019 to 2023.

** See 2019 Ontario Budget page 245 for list of consensus forecasters. Forecasts as of April 26th, 2019.

*** Business Investment is Non-residential Investment and Machinery & Equipment.

Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Ontario Budget, Ontario Economic Accounts, Ontario Ministry of Finance and FAO.

Table 2: FAO Outlook for Selected Economic Indicators

|

2017a |

2018a |

2019f |

2020f |

2021f |

2022f |

2023f |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Employment (Per Cent Growth) |

|||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

1.8 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

1.8 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Unemployment Rate (Per Cent) |

|||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

6.0 |

5.6 |

5.6 |

5.7 |

5.8 |

5.9 |

6.0 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

6.0 |

5.6 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

|

Labour Force (Per Cent Growth) |

|||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Population Growth (Per Cent) |

|||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

CPI Inflation (Per Cent Growth) |

|||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

1.7 |

2.4 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

1.7 |

2.4 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

1.7 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

|

Canada Real GDP (Per Cent Growth) |

|||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

3.0 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

3.0 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.6 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

|

U.S. Real GDP (Per Cent Growth) |

|||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

2.2 |

2.9 |

2.3 |

2.0 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

2.2 |

2.9 |

2.5 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

2.1 |

|

Canadian Dollar (Cents US) |

|||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

77.0 |

77.2 |

76.0 |

76.6 |

76.6 |

76.7 |

76.7 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

77.0 |

77.2 |

76.0 |

77.3 |

77.9 |

79.1 |

80.0 |

|

Three-month Treasury Bill Rate (Per Cent) |

|||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

0.7 |

1.4 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

|

2019 Ontario Budget |

0.7 |

1.4 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

|

10-year Government Bond Rate (Per Cent) |

|||||||

|

FAO - Spring 2019 |

1.8 |

2.3 |

2.1 |

2.5 |

2.7 |

2.9 |

3.1 |

a = Actual f = Forecast

Source: Statistics Canada, US Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2019 Ontario Budget, Bank of Canada and FAO.

Table 3a: FAO Baseline Fiscal Outlook

|

($ Billions) |

2017a |

2018f |

2019f |

2020f |

2021f |

2022f |

2023f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Revenue |

|||||||

|

Personal Income Tax |

32.9 |

34.9 |

36.3 |

38.0 |

39.8 |

41.7 |

43.7 |

|

Sales Tax |

25.9 |

27.9 |

27.6 |

28.5 |

29.5 |

30.6 |

31.7 |

|

Corporations Tax |

15.6 |

15.1 |

14.5 |

15.1 |

15.7 |

16.3 |

17.2 |

|

All Other Taxes |

25.3 |

25.5 |

26.1 |

26.8 |

27.6 |

28.3 |

29.1 |

|

Total Taxation Revenue |

99.7 |

103.4 |

104.4 |

108.4 |

112.6 |

117.0 |

121.7 |

|

Transfers from Government of Canada |

24.9 |

25.1 |

25.3 |

26.4 |

27.0 |

27.8 |

28.7 |

|

Income from Government Business Enterprise |

6.2 |

4.9 |

5.8 |

6.2 |

6.9 |

7.0 |

7.2 |

|

Other Non-Tax Revenue |

19.9 |

17.4 |

16.8 |

17.2 |

17.6 |

18.1 |

18.6 |

|

Total Revenue |

150.6 |

150.7 |

152.3 |

158.1 |

164.0 |

170.0 |

176.2 |

|

Expense |

|||||||

|

Program Expense |

142.4 |

150.0 |

150.1 |

152.0 |

153.2 |

154.8 |

156.3 |

|

Interest on Debt |

11.9 |

12.5 |

13.0 |

13.4 |

13.6 |

13.7 |

13.6 |

|

Total Expense* |

154.3 |

162.5 |

163.1 |

165.4 |

166.8 |

168.4 |

169.9 |

|

Budget Balance** |

-3.7 |

-11.7 |

-10.8 |

-7.3 |

-2.7 |

1.5 |

6.4 |

a = Actual f = Forecast

* In a departure from standard practice program spending by major sector has not been disclosed as this information is deemed to be a Cabinet record.

**Budget Balance is presented without reserve.

Note: Years represent fiscal years starting in number presented (i.e. 2017 is fiscal year 2017-18). Numbers may not add up due to rounding.

Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Budget, Ontario Public Accounts and FAO.

Table 3b: FAO Baseline Debt Outlook

|

($ Billions) |

2017a |

2018f |

2019f |

2020f |

2021f |

2022f |

2023f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Budget Balance* |

-3.7 |

-11.7 |

-10.8 |

-7.3 |

-2.8 |

1.5 |

6.4 |

|

Accumulated Deficit |

209.0 |

220.8 |

231.5 |

238.8 |

241.6 |

240.1 |

233.7 |

|

Net Debt |

323.8 |

343.4 |

361.4 |

375.3 |

383.6 |

386.1 |

384.6 |

|

Net Debt to GDP (Per Cent) |

39.2% |

40.2% |

41.0% |

41.3% |

40.8% |

39.7% |

38.2% |

a = Actual f = Forecast

*Budget Balance is presented without reserve.

Note: Years represent fiscal years starting in number presented (i.e. 2017 is fiscal year 2017-18). Numbers may not add up due to rounding.

Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Budget, Ontario Public Accounts and FAO.

Table 4: Provincial Comparisons

|

Fiscal Performance (2017-18) |

NL |

PE |

NS |

NB |

QC |

Ontario |

MB |

SK |

AB |

BC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total Revenue |

||||||||||

|

Per Capita ($) |

13,773 |

12,610 |

11,129 |

12,178 |

13,026 |

10,702 |

12,127 |

12,182 |

11,144 |

10,569 |

|

to GDP (%) |

22.0 |

28.5 |

24.8 |

25.9 |

25.9 |

18.2 |

22.8 |

17.6 |

14.2 |

18.4 |

|

Total Program Expenditures |

||||||||||

|

Per Capita ($) |

13,609 |

11,776 |

10,493 |

11,222 |

11,358 |

10,117 |

11,935 |

11,958 |

12,700 |

9,974 |

|

to GDP (%) |

21.7 |

26.7 |

23.4 |

23.8 |

22.6 |

17.2 |

22.4 |

17.3 |

16.2 |

17.4 |

|

Interest on Debt |

||||||||||

|

Per Capita ($) |

1,888 |

826 |

867 |

869 |

1,114 |

846 |

713 |

487 |

335 |

533 |

|

to GDP (%) |

3.0 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.9 |

|

to Revenue (%) |

13.7 |

6.6 |

7.8 |

7.1 |

8.5 |

7.9 |

5.9 |

4.0 |

3.0 |

5.0 |

|

Total Expenditures |

||||||||||

|

Per Capita ($) |

15,496 |

12,602 |

11,361 |

12,091 |

12,472 |

10,963 |

12,648 |

12,445 |

13,034 |

10,507 |

|

to GDP (%) |

24.8 |

28.5 |

25.3 |

25.7 |

24.8 |

18.7 |

23.8 |

18.0 |

16.7 |

18.3 |

|

Primary Balance |

||||||||||

|

Per Capita ($) |

165 |

834 |

1,109 |

957 |

1,667 |

585 |

192 |

224 |

-1,556 |

594 |

|

to GDP (%) |

0.3 |

1.9 |

2.5 |

2.0 |

3.3 |

1.0 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

-2.0 |

1.0 |

|

Deficit (-) or surplus |

||||||||||

|

Level (Millions $) |

-911 |

1 |

230 |

67 |

4,596 |

-3,672 |

-695 |

-303 |

-8,023 |

301 |

|

Per Capita ($) |

-1,723 |

8 |

242 |

87 |

554 |

-261 |

-520 |

-263 |

-1,890 |

61 |

|

to GDP (%) |

-2.8 |

0.0 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

1.1 |

-0.4 |

-1.0 |

-0.4 |

-2.4 |

0.1 |

|

Net Debt |

||||||||||

|

Level (Millions $) |

14,674 |

2,208 |

14,959 |

13,926 |

179,278 |

323,834 |

24,365 |

11,288 |

19,344 |

41,869 |

|

Per Capita ($) |

27,761 |

14,662 |

15,735 |

18,160 |

21,606 |

23,014 |

18,246 |

9,809 |

4,558 |

8,506 |

|

to GDP (%) |

44.4 |

33.2 |

35.0 |

38.6 |

43.0 |

39.2 |

34.3 |

14.2 |

5.8 |

14.8 |

|

Economic and Demographic Indicator Growth (2017) (Per Cent) |

||||||||||

|

Real GDP |

1.0 |

3.5 |

1.5 |

1.7 |

2.8 |

3.1 |

3.7 |

2.9 |

5.5 |

3.9 |

|

Nominal GDP |

4.3 |

4.8 |

2.9 |

4.3 |

5.0 |

4.1 |

5.4 |

4.8 |

10.0 |

6.9 |

|

Employment |

-3.7 |

3.1 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

2.2 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

-0.2 |

1.0 |

3.7 |

|

Population |

-0.2 |

2.4 |

0.8 |

0.5 |

0.9 |

1.4 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

Source: FAO, Department of Finance Canada’s Fiscal Reference Tables (October 2018) and Statistics Canada.

5 | About this document

Established by the Financial Accountability Officer Act, 2013, the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) provides independent analysis on the state of the province’s finances, trends in the provincial economy and related matters important to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario.

The FAO’s Economic and Budget Outlook (EBO) reports are released each spring and fall, providing an assessment of the province’s medium-term economic performance and fiscal position.

This report was prepared by Jay Park, Zohra Jamasi, Luan Ngo, Edward Crummey and Ben Premi-Reiller, under the direction of David West, and with contributions from Jeffrey Novak, Greg Hunter, Matt Gurnham, and Michelle Gordon. External reviewers were provided with earlier drafts of this report for their comments. However, the input of external reviewers implies no responsibility for this final report, which rests solely with the FAO.

The content of this report is based on information available to May 7, 2019. Background data used in this report are available upon request.

In keeping with the FAO’s mandate to provide the Legislative Assembly of Ontario with independent economic and financial analysis, this report makes no policy recommendations.

FAO’s Fiscal Projections

The FAO forecasts provincial finances based on projections of existing and announced revenue and spending policies. The FAO’s tax revenue projections are based on an assessment of the outlook for the provincial economy and current tax policies. Given the government’s discretion over spending, the FAO adopts the government’s announced spending plans from fiscal documents and incorporates policy announcements as appropriate. Beyond the government’s published spending projections, the FAO forecasts spending based on the outlook for underlying cost drivers including demographics and price inflation.

[1] The FAO projects real GDP growth will average 1.6 per cent from 2019 to 2023, significantly slower than the 2.5 per cent average from 2014 to 2017.

[2] The FAO’s baseline budget projection incorporates the FAO’s revenue outlook and adopts the government’s plans to restrain program spending growth from the 2019 Budget. Any implied but unannounced revenue or spending measures included in the 2019 budget have not been incorporated into the FAO’s baseline projection.

[3] According to reports by TD Bank and QP Briefing, government officials confirmed that the 2019 Ontario Budget’s fiscal projection included provisions for reductions in both personal income tax and gasoline tax beginning 2021-22.

[4] See page 35 of the 2019 Ontario Budget.

[5] A portion of these additional cost reductions may already be reflected in the 2019 budget plan, although the FAO was unable to identify the specific assumptions or measures.

[6] From 2014 to 2017, real GDP growth averaged 2.5 per cent, the fastest pace of growth since the mid-2000s.

[7] International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April 2019. In their World Economic Outlook from October 2018, the IMF forecast annual world economic growth of 3.7 per cent in 2018 and 2019.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2019 to 2029, January 2019. The FAO’s projection is based on the assumption that the US government shutdown in December and January will not materially affect Ontario’s annual growth in 2019. For the impact on the US economy, see Congressional Budget Office, The Effects of the Partial Shutdown Ending in January 2019, January 28, 2019.

[12] Capital Economics, US Economic Outlook, April 2019.

[13] Federal Open Market Committee Press Release, January 29-30, 2019 FOMC Meeting and March 29-30, 2019 FOMC Meeting.

[14] International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April 2019.

[15] The policy interest rate is the ‘target for the overnight rate’, which is the rate at which major Canadian financial institutions can borrow from one another.

[16] Bank of Canada, Monetary Policy Report, April 2019.

[17] Retail sales have declined in three of the past five months while housing starts and home resales were both down in the first quarter of 2019. Additionally, manufacturing sales, exports and imports were all weak in February.

[18] The FAO estimates that provincial spending restraint could slow real GDP growth by an average of 0.2 per cent per year over the outlook. Specifically, weaker increases in government spending dampen growth in employment and labour income, leading to lower gains in household consumption and residential investment.

[19] While technical recessions are typically characterized by two consecutive quarterly declines in real GDP, the two-quarter decline in Ontario’s real GDP in 2003 was not treated as a recession due to the unique temporary factors which caused the downturn.

[20] This is an upward revision since last fall. Household debt-to-disposable income ratio data is from Statistics Canada Table: 36-10-0590-01.

[21] Total liabilities data is from Statistics Canada Table 36-10-0586-01. Disposable income data is from Statistics Canada Table 36-10-0588-01.

[22] Debt service ratio data is from Statistics Canada Table 36-10-0226-01.

[23] The Bank of Canada estimates that trade uncertainty will reduce Canadian business investment by 2.5 per cent by 2021. Bank of Canada, Monetary Policy Report, April 2019.

[24] CBC News, ‘Ottawa considering new retaliation to end U.S. tariff fight, source says’. March 2019

[25] The FAO baseline projection is based on current and announced fiscal policies.

[26] See page 35 of the 2019 Ontario Budget.

[27] The absence of any revenue growth in 2018-19 is the result of the loss of several time-limited revenues which boosted revenue in 2017-18, combined with several policy changes announced since the 2018 budget, which lowered revenue last year.

[28] The loss of cap and trade revenue is partially offset by lower expenses from related programs. See the FAO’s Cap and Trade Report.

[29] Tax changes in the 2018 budget included the elimination of the personal income tax (PIT) surtax and associated adjustments to PIT brackets and rates, and changes to the application of the small business limit and the Employer Health Tax exemption. See the FAO’s 2018 Fall Economic and Budget Outlook.

[30] These changes include paralleling the accelerated capital cost allowance measure introduced by the federal government (and referred to as the ‘Ontario Job Creation Investment Incentive’ by the Ontario government).

[31] The government projects federal transfers revenue to be $0.3 billion higher than the FAO, partially offsetting its projection for $1.5 billion in lower taxation revenue.

[32] According to reports by TD Bank and QP Briefing, government officials confirmed that the 2019 Ontario Budget’s fiscal projection included provisions for reductions in both personal income tax and gasoline tax beginning 2021-22, consistent with campaign promises made by the Ontario Progressive Conservative party during the 2018 Provincial Election.

[33] The FAO estimated an alternative tax revenue projection based on the 2019 budget’s economic forecast to isolate the fiscal impact of these unannounced tax policy changes. The gap between this alternate projection and the actual tax revenues projected in the 2019 budget is assumed to represent the implied impact of unannounced policy measures. (Additional details on this calculation are available on request.)

[34] Based on existing and announced policies proposed in the 2019 budget, program spending would grow at an annual average pace of 0.8 per cent over the next five years, somewhat slower than the 1.0 per cent average annual growth presented in the 2019 budget.

[35] See page 35 of the 2019 Ontario Budget.

[36] The starting point for the government’s status quo projection was the 2018-19 level of program spending as reported by the Independent Financial Commission of Inquiry.

[37] Average growth of 3.3 per cent is somewhat slower than the FAO’s estimate in the Fall 2018 Economic and Budget Outlook (due to a downward revision in the FAO’s projection for consumer price inflation), but in-line with the government’s estimate of “status quo” program spending growth.

[38] When publicly available, the FAO provides cost estimates of these program changes. If not publicly available, the FAO is unable to disclose the fiscal impact of these program changes as the Province has deemed this information to be a Cabinet record. The FAO is prevented from disclosing Cabinet records under s.12(2) of the Financial Accountability Officer Act, 2013 and Order-in-Council 1002/2018.

[39] 2018 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, page 68.

[40] See the 2019 Ontario Budget, page 8.

[41] See the 2019 Ontario Budget, page 278.

[42] See the 2019 Ontario Budget, page 276.

[43] A portion of these additional cost reductions may already be reflected in the 2019 budget plan, although the FAO was unable to identify the specific assumptions or measures.

[44] See the Ontario Auditor General’s review of eHealth, the Province’s effort to digitize health records, or the Auditor General of Canada’s report on the Federal government’s attempt to centralize pay services.

[45] The FAO’s baseline budget projection incorporates the FAO’s revenue outlook and adopts the government’s plans to restrain program spending growth from the 2019 Budget -which assumes that the government will identify the additional cost savings required to achieve the budget’s spending plan. The FAO’s baseline projection reflects the office’s established approach of incorporating existing and announced revenue and spending policies into its projection.

[46] FAO Economic and Budget Outlook, Fall 2018.

[47] In the 2019 budget, the government projected capital investments would average $16.6 billion per year from 2018-19 to 2023-24, about one-quarter lower than projected in the 2018 budget plan.

[48] In the 2019 budget (page 35), the government committed to reducing the net debt-to-GDP ratio to below 40.8 per cent by 2022-23.

[49] Including unannounced measures, the FAO projects budget deficits that are slightly higher than forecast in the 2019 budget, due to the FAO’s projection for slower revenue growth relative to the budget outlook.

[50] This is equivalent to $4.6 billion in higher program spending by 2023-24, compared to the FAO’s baseline projection.

[51] See ‘Budget Sensitivities’ for FAO estimates of the fiscal impacts of various policy options.

[52] Pre-2009 program spending data is from Statistics Canada table 385-0001. The earliest available year is 1989.

[53] One example is the increasing efficiency of Ontario’s hospitals, see FAO’s 2018 Health Sector report.

[54] See the FAO’s Assessing Ontario Government Employment and Wage Expense.

[55] In a 2015 report, the Auditor General indicated that “significant infrastructure investments are needed to maintain Ontario’s existing schools and hospitals, which current funding levels cannot meet.” See the Auditor General’s 2015 Annual Report, page 289.

[56] For example, hospitals received increases in base operating funding and the recent arbitration decision with the Ontario Medical Association reversed some of the compensation restraint that was imposed on Ontario’s doctors in 2013 and 2015. See the FAO’s Ontario Health Sector: 2019 updated assessment of Ontario health spending.

[57] For example, the 2017 budget introduced OHIP+, a program to provide universal drug coverage to all children and youth in Ontario. See the 2017 Ontario Budget, page 25.

[58] 2019 Ontario Budget, page 276.

[59] 2019 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, page 68.

[60] All figures are from 2019 Ontario Budget, pages 8, 276 and 277.

[61] See the 2019 Ontario Budget, pp. 99-100.

[62] See the 2019 Ontario Budget, page 278.

The Province’s spending restraint would result in a $6.4 billion surplus by 2023-24

This chart compares the Ontario budget balance under the FAO baseline projection excluding unannounced measures and the 2019 budget plan, between 2017-18 and 2023-24. Historically in 2017-18, the budget balance was $-3.7 billion. Under the FAO baseline projection, the budget balance is projected to be -$11.7 billion dollars in 2018-19, -$10.8 billion in 2019-20, -$7.3 billion in 2020-21, -$2.8 billion in 2021-22 and $1.5 billion in 2022-23. This chart emphasizes that by 2023-24, the budget balance under the FAO baseline projection is expected to reach $6.4 billion while the budget balance under the 2019 budget plan is projected to reach $1.9 billion. The chart highlights that unannounced measures are incorporated into the 2019 budget plan beginning in 2021-22.

The 2019 budget plans to lower program spending by $1,100 per Ontarian by 2023-24

This chart shows total program spending per capita under the FAO status quo projection and the 2019 budget plan between 2012-13 and 2023-24 in 2018 constant dollars. The chart highlights that in 2018-19, per capita program spending is projected to be $10,494. It shows that under the 2019 budget plan, per capita program spending would decrease by $1,100 to $9,391 by 2023-24.

Economic growth is slowing in Ontario

This chart shows the historical and forecasted growth rates for Ontario’s nominal and real GDP from 2014 to 2023. Real GDP grew by 2.2 per cent in 2018. The FAO forecasts real GDP growth of 1.4 per cent in 2019, 1.5 per cent in 2020, 1.6 per cent in 2021, and 1.7 per cent in 2022 and 2023. Nominal GDP grew by 3.4 per cent in 2018. The FAO forecasts nominal GDP growth of 3.2 per cent in 2019 and 2020, 3.4 per cent in 2021 and 3.5 per cent in 2022 and 2023.

Steady global growth expected over the outlook

This chart shows the historical and forecasted real GDP growth for the world, advanced economies, and emerging market and developing economies from 2011 to 2023. Global real GDP growth was 3.6 per cent in 2018 and expected to grow at 3.3 per cent in 2019. Advanced economies grew at 2.2 per cent in 2018 and are expected to grow at 1.8 per cent in 2019. Emerging market and developing economies grew at 4.5 per cent in 2018 and are expected to grow at 4.4 per cent in 2019.

US economy expected to moderate as fiscal stimulus ends

This chart shows the historical and forecasted US real GDP growth rates from 2016 to 2023. The US economy grew by 1.6 per cent in 2016, 2.2 per cent in 2017 and 2.9 per cent in 2018. US real GDP growth is expected to grow at 2.3 per cent in 2019, 2.0 per cent in 2020 and 1.9 per cent from 2021 to 2023.