Key Points

- In the 2019 Spring Economic and Budget Outlook (EBO), the FAO forecasted slower but steady economic growth in Ontario over the next five years. Based on this economic outlook, the FAO projected that the government would achieve a modest surplus of $0.9 billion by 2023-24, when the unannounced revenue and spending measures built into the 2019 Ontario Budget are included.[1]

- Given the relatively elevated level of risk for the outlook and the critical importance of continued economic growth for the government’s fiscal plan, the FAO assessed the vulnerability of the government’s budget plan to an economic downturn.

- Specifically, the FAO constructed a hypothetical, but reasonable, recession scenario to explore the implications for the government’s finances. Under this recession scenario, the Ontario economy would experience a relatively moderate downturn in 2020 before fully recovering by 2023.[2]

- Due to weaker economic activity, the recession would result in government revenues declining while spending on some government programs, such as employment training and social services, would be expected to increase automatically. Taken together, the FAO estimates that the deficit would increase by $10.8 billion to $16.5 billion in 2021-22, which would be the largest deficit since 2010-11. While the budget deficit would be expected to improve steadily as the economy recovers from the recession, a budget deficit of over $4 billion would still be projected in 2023-24, the year the government intends to achieve balance, based on the 2019 budget plan.

- Under this recession scenario, Ontario would be expected to accumulate almost $31 billion in additional debt by 2023-24. The combination of higher debt and slower economic growth would increase Ontario’s net debt-to-GDP ratio from 41 per cent this year to nearly 45 per cent by 2021-22. Even as the economy recovers, the additional debt would remain on the provincial balance sheet as a legacy of the recession.

- Based on the FAO’s analysis, the government’s fiscal plan is vulnerable to an economic downturn. The significant deterioration in Ontario’s fiscal position that would result from a moderate recession would put the government’s commitments to both balance the budget and limit increases in Ontario’s debt-to-GDP ratio at risk.

Overview and Purpose

In the 2019 Spring Economic and Budget Outlook (EBO), the FAO projected slower but steady economic growth over the next five years. However, the FAO’s outlook for slower growth also occurs in an environment of elevated economic risks that include heavily indebted Ontario households and an uncertain trade and investment environment.

In this economic context, the Ontario government’s 2019 budget plan included provisions to introduce several significant but unannounced policy measures[3], while also committing to balance the budget by 2023-24 and limiting Ontario’s net debt-to-GDP ratio to a maximum of 40.8 per cent. The government’s fiscal plan relies critically on continued, steady revenue growth combined with successfully restraining the growth in program spending.

Given the elevated level of economic risk and the critical importance of continued economic and revenue growth, the FAO assessed the vulnerability of the government’s budget plan to an economic recession.[4] To stress test the Province’s fiscal plan, the FAO constructed a hypothetical, but reasonable, recession scenario to explore the implications of an economic downturn on the government’s finances.

Recessions and Current Economic Risks

Periods of economic growth are inevitably disrupted by recessions. While there is no single, authoritative technical definition for what constitutes a recession, experts agree that these events are characterized by significant and broad-based declines in economic activity that typically last several quarters.[5]

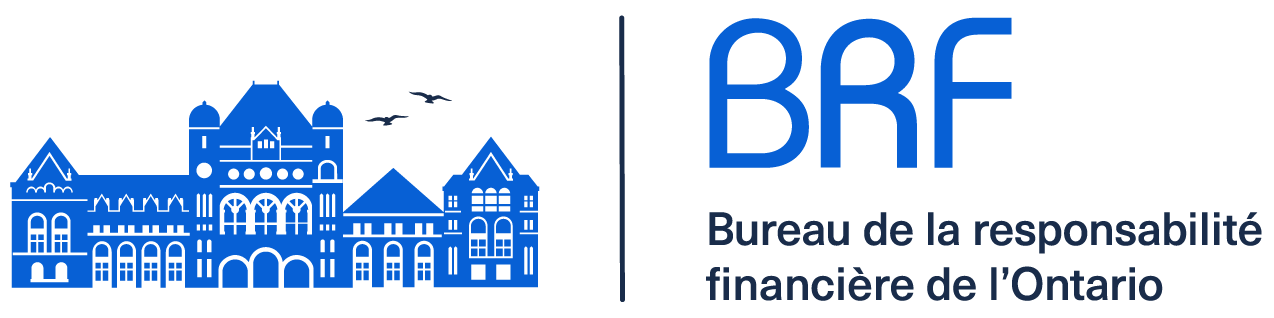

Based on this description, Ontario has arguably experienced three recessions over the last four decades.[6] The seven-year period of expansion in the 1980s was disrupted by the 1990 recession, and the 16-year expansionary period from the 1990s to the late 2000s was interrupted by the 2008 recession. The current period of expansion, if it continues, would reach at least 15 years – close to the longest expansionary period over the past four decades.

Ontario has experienced three recessions over the last four decades

* Note: Forecast is the FAO’s 2019 Spring EBO outlook.

Source: Ontario Economic Accounts and FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows historical and forecasted real GDP in Ontario from 1981 Q1 to 2023 Q4. The chart highlights three recessions followed by periods of expansions. The first recession was in the early 1980s, followed by a seven-year expansion period. The second recession was in the early 1990s, followed by a 16-year expansion period. The third recession was in 2008, followed by a 15-year expansion period including the FAO’s economic forecast.

Recessions can be caused by a number of factors including commodity price surges, interest rate spikes, financial sector imbalances or international crises. Currently, global trade tensions and Ontario’s elevated household debt are key economic risks facing the province.

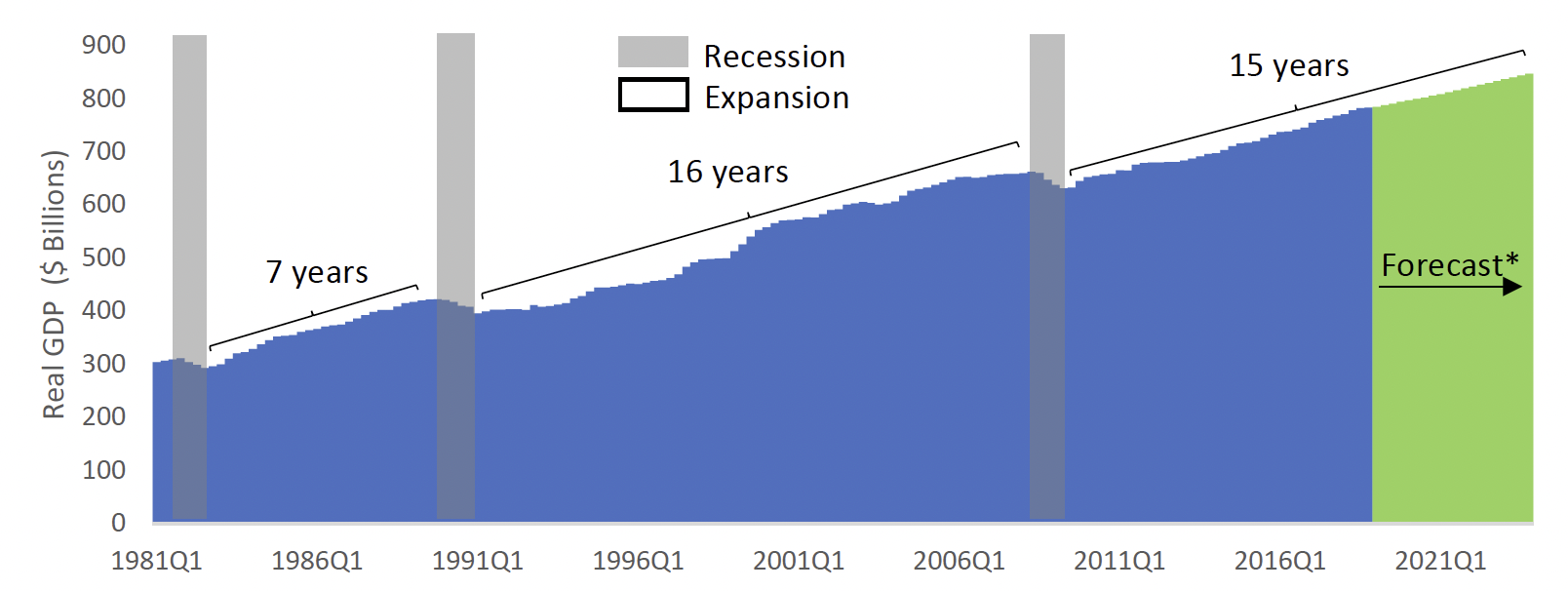

Household debt continues to rise in Ontario

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows the historical household debt-to-disposable income ratios in Ontario and the rest of Canada from 2010 to 2017. Ontario’s household debt-to-income ratio was 162 per cent in 2010 and grew to 189 per cent by 2017. Household debt-to-income ratio in the rest of Canada was 171 per cent in 2010 and grew to 180 per cent by 2017.

The ongoing trade conflict between the United States and China continues to present major headwinds for the global economy. Recently, the U.S. government significantly raised tariffs on Chinese goods imported into the United States, escalating the trade conflict. Higher tariffs impose higher prices on U.S. consumers and businesses, potentially forcing both sectors to scale back spending.[7] Several U.S. economic forecasters – Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs Group[8] – have indicated that higher tariffs would curtail economic growth and raise the risk of a recession in 2020. Given Ontario’s reliance on international trade, a downturn in the global economy, and in particular the United States, would have significant consequences for Ontario.

Domestically, the most significant economic risk has been the sharp rise in Ontario household debt to record levels. An external event which slows wage growth or increases unemployment could cause Ontario households to scale back spending dramatically, amplifying the effects of an economic downturn. Elevated levels of household debt, combined with high corporate and government debt levels, could also prolong a recession by limiting the effects of measures designed to stimulate the economy.

A Hypothetical Recession Scenario

Despite these elevated economic risks, predicting the exact timing, magnitude and catalyst of the next recession has always proven to be challenging. Given the difficulty of predicting the precise nature of the next recession, the FAO constructed a hypothetical recession scenario based on historical downturns rather than attempting to identify the specific catalysts that might trigger the next recession (e.g. unexpected interest rate hikes or global trade disruptions).

Consistent with the views of other economic forecasters[9], the FAO’s recession scenario assumes that a moderate economic downturn would begin in the second half of 2020, with real GDP declining by just over 1 per cent at annual rates.[10] This hypothetical recession is assumed to be relatively short-lived, with the economy regaining the lost ground by 2023.

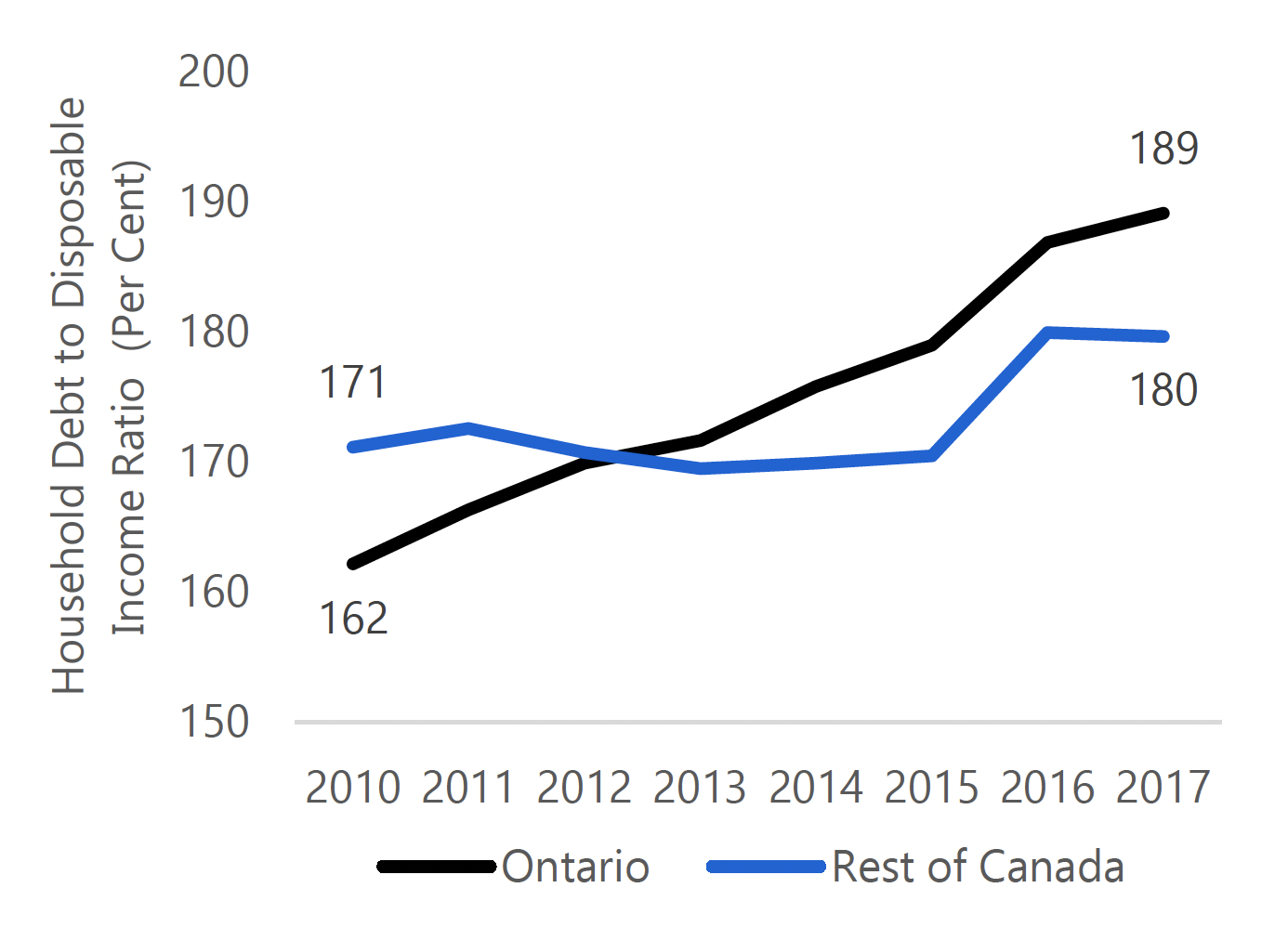

The FAO recession scenario assumes a relatively moderate decline compared to previous Ontario recessions and a comparatively quicker recovery. Under the scenario, real GDP is assumed to be about 3 per cent lower at the trough compared to its level in 2019. In contrast, over the past three recessionary periods (in 1982, 1990 and 2008), real GDP declined by between 5 and 7 per cent from its pre-recession high.

Comparison of FAO’s recession scenario with past Ontario recessions

Source: FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows the real GDP index of past Ontario recessions and the FAO recession scenario. The starting point for each recession is the quarter before the recession, where the real GDP index is 100. In the past three recessions, real GDP declined by between 5 and 7 per cent from before the recession. The FAO recession scenario assumes that real GDP declines by about 3 per cent at the trough.

Economic Impact

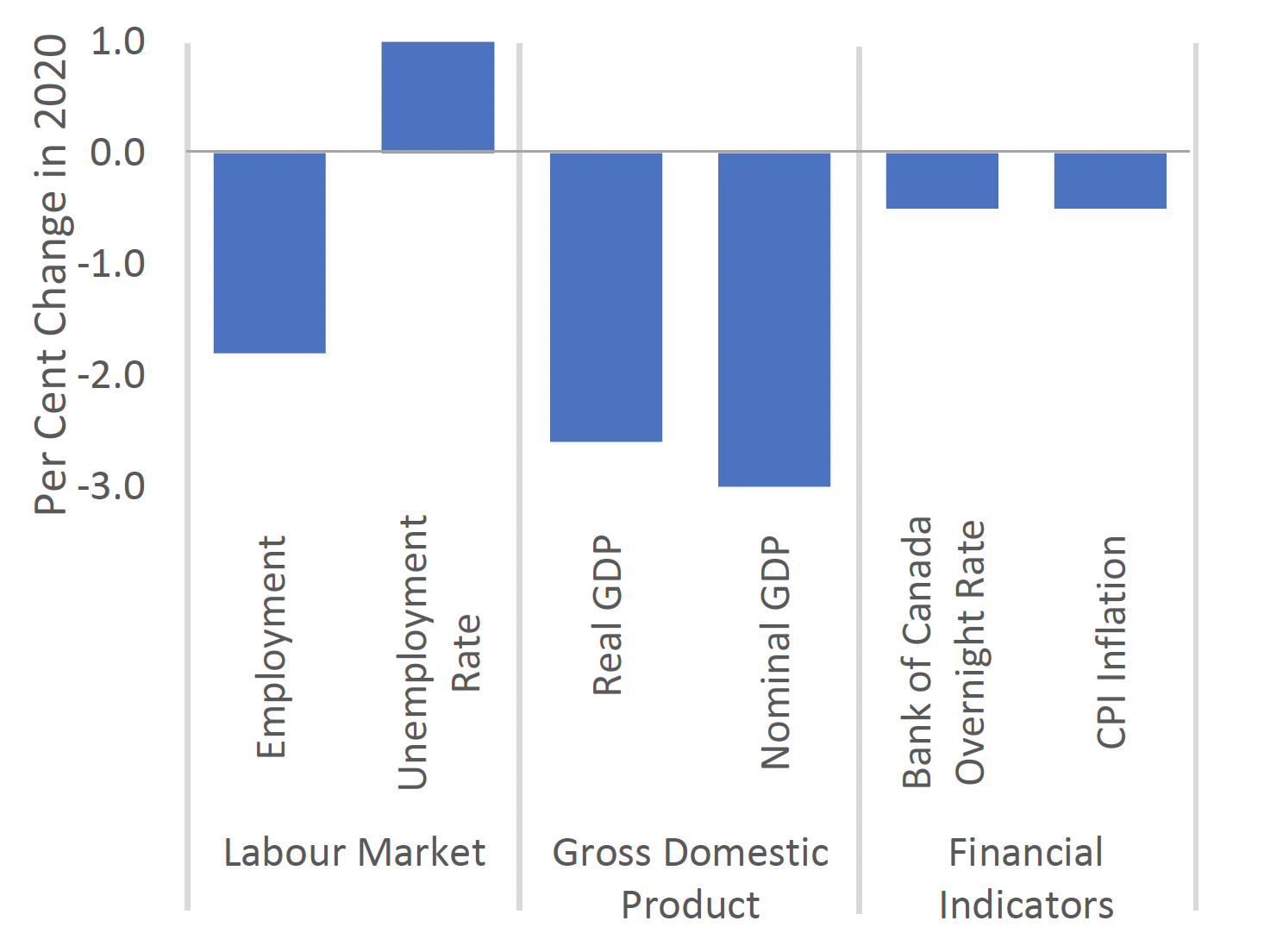

Summary of economic impacts in 2020 compared to 2019 Spring EBO

Source: FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows the economic impacts of the FAO recession scenario in 2020 compared to the FAO forecast in the 2019 Spring EBO. Under the FAO recession scenario, employment is lower by 1.8 per cent, the unemployment rate is higher by 1.0 percentage point, real GDP is lower by 2.6 per cent, nominal GDP is lower by 3.0 per cent, the Bank of Canada overnight rate is lower by 50 basis points and CPI inflation is lower by 0.5 per cent.

Under the recession scenario, the FAO assumes that all components of the economy – including household spending, business investment and net trade – weaken proportionally, leading to a decline in real GDP relative to the FAO’s base case projection.[11] As a result of the lower economic output, businesses would reduce employment, leading to a rise in Ontario’s unemployment rate by 1 percentage point. The weaker labour market would lead to stagnant growth in wages in 2020.

Lower employment and wage growth would weaken gains in labour income, the largest component of nominal GDP. With corporate profits also declining[12], Ontario’s nominal GDP – the broadest measure of the government’s revenue base – would be expected to fall by 3.0 per cent in 2020 compared to the FAO’s base case projection.

With lower wage pressures and unused economic capacity, consumer price inflation would be subdued, averaging 1.5 per cent in 2020. In response to the lower inflation, the FAO assumes the Bank of Canada would reduce its overnight rate by 50 basis points in 2020, while non-discretionary government spending (such as employment insurance and social assistance) would increase automatically (see Fiscal Impact section).

Lower interest rates would be expected to boost household spending and business investment, while higher non-discretionary government spending would have a direct positive impact on the economy. As a result, Ontario’s economy would begin to stabilize in 2021, leading to a full recovery by 2023.

Factors which could lead to a more prolonged recession

Ontario’s elevated household and corporate debt levels[13] could amplify and prolong the effects of a downturn. The effectiveness of the government’s response to a recession, such as cutting taxes to stimulate the economy, may be more muted than in the past because indebted households may save rather than spend a larger portion of the extra disposable income than was the case historically. In addition, due to Ontario’s aging workforce, a recession could have permanent effects on Ontario’s production capacity. Since many workers are near retirement age, those who voluntarily or involuntarily leave their jobs during a recession may decide to retire[14], reducing Ontario’s labour force and economic potential. As a result, following the recession, the economy may not fully recover to the level of output that would have otherwise occurred in the absence of the recession.

Fiscal Impact

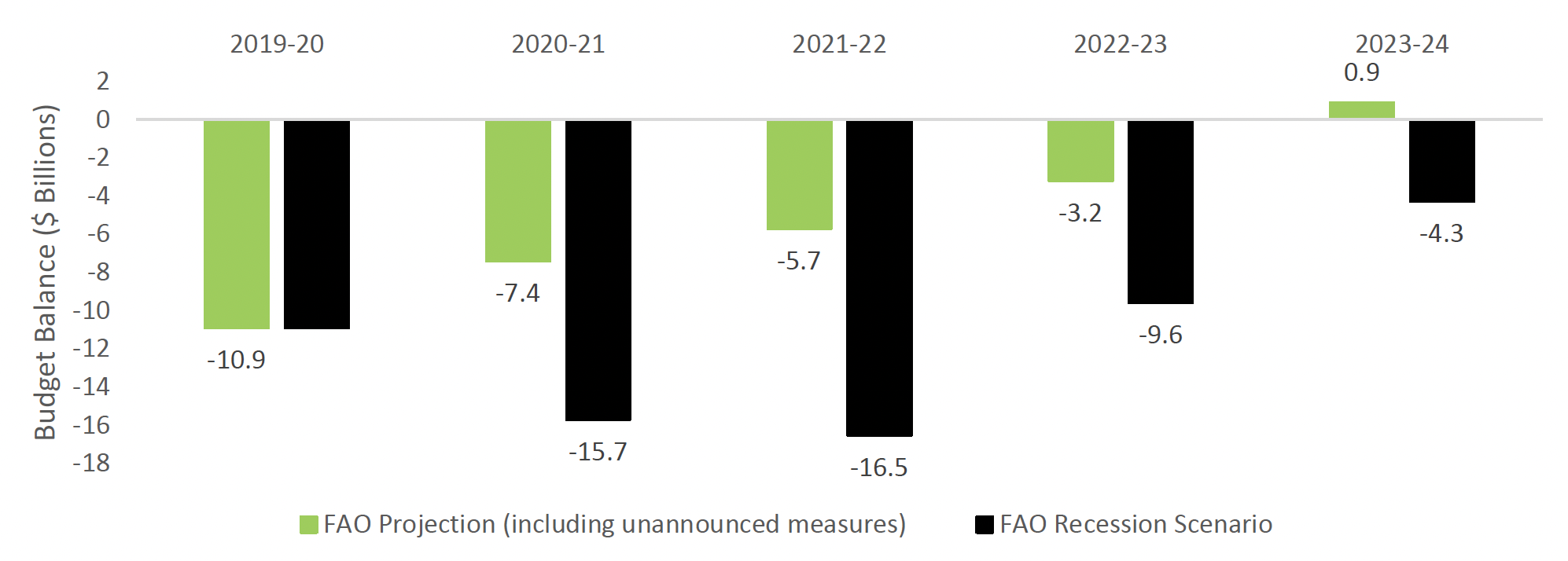

In the 2019 Spring EBO, the FAO projected Ontario’s budget will rapidly improve to a surplus of $6.4 billion by 2023-24. Importantly, this projection excluded the relatively large unannounced revenue reductions and spending measures that were incorporated into the government’s 2019 budget plan.[15] Including these unannounced measures, the FAO estimates that the Ontario budget surplus would be reduced to $0.9 billion in 2023-24, given the EBO forecast for steady, but moderate economic growth.

In a recession, governments generally provide additional fiscal stimulus, such as tax cuts or spending increases, to stabilize the economy.[16] Since the exact size and nature of the fiscal stimulus is uncertain, the FAO’s recession scenario assumes that the government would implement these unannounced measures from the 2019 budget to stimulate an economic recovery.

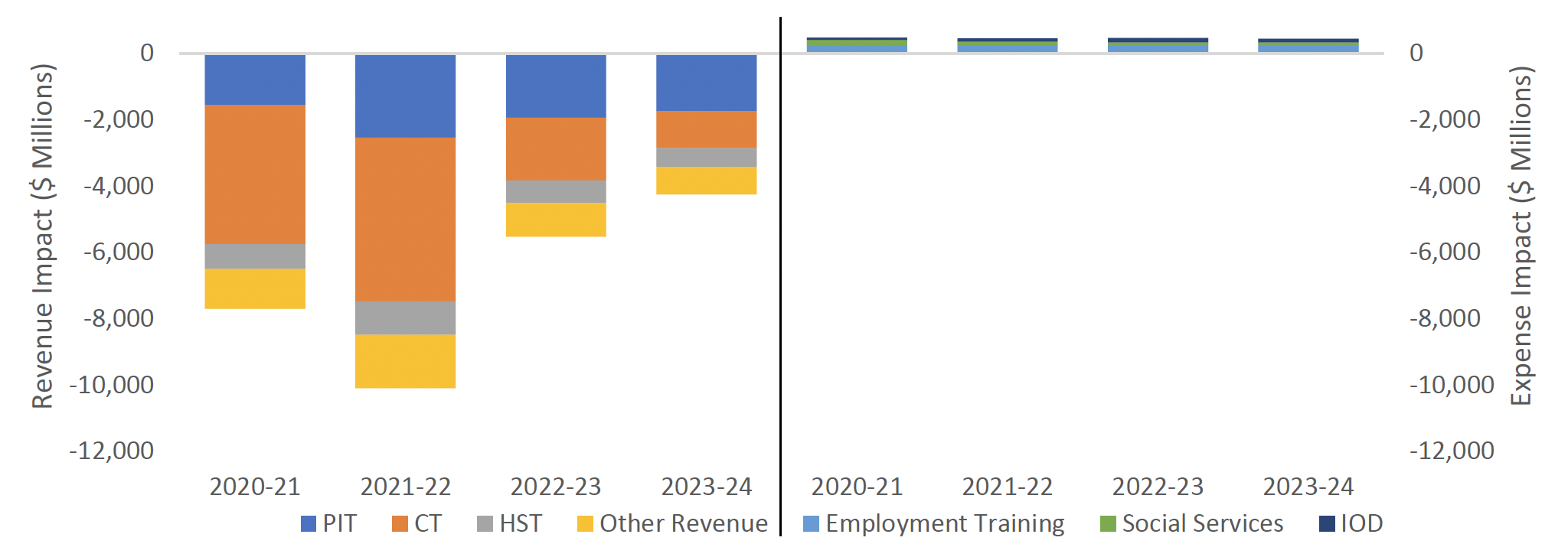

Under the FAO’s recession scenario, weaker economic activity would reduce the Province’s revenues while spending on some non-discretionary programs would be expected to increase. The FAO estimates that lower labour income, corporate profits and household spending combined with a reduction in tax yields[17] would lower Ontario’s total revenues by $7.7 billion in 2020-21 and $10.1 billion in 2021-22.

At the same time, some non-discretionary government spending, such as employment training and social assistance, would be expected to increase in response to the recession. In total, the FAO estimates that program spending would increase by a relatively moderate $0.4 billion in 2020-21. In addition, interest on debt expenses would also be marginally higher, as the increased borrowing from higher deficits is partially offset by lower interest rates.

Impact on revenue and expenses

Source: FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows the impact of the FAO recession scenario on revenue and expenses from 2020-21 to 2023-24. For revenues, the chart shows the impacts on personal income tax, corporate tax, sales tax and other revenue. For expenses, the chart shows the impacts on employment training, social services and interest on debt.

Taken together, the FAO estimates that the economic drag caused by the recession would increase the deficit from $7.4 billion in 2020-21 to $15.7 billion.[18] The deficit would be expected to worsen to $16.5 billion in 2021-22 before beginning to improve over the following two years as the economy recovers. However, a budget deficit of $4.3 billion would still be expected in 2023-24, the year the government has committed to achieving a balanced budget, based on the 2019 budget plan.

A moderate recession would lead to higher deficits over the outlook

Source: FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows Ontario’s budget balance from 2019-20 to 2023-24 under the FAO projection (including unannounced measures) and the FAO recession scenario. Under the FAO projection, Ontario’s deficit of $10.9 billion in 2019-20 improves gradually to a $0.9 billion surplus in 2023-24. Under the FAO recession scenario, the deficit increases to $15.7 billion in 2020-21 and worsen in 2021-22 before improving steadily to $4.3 billion in 2023-24.

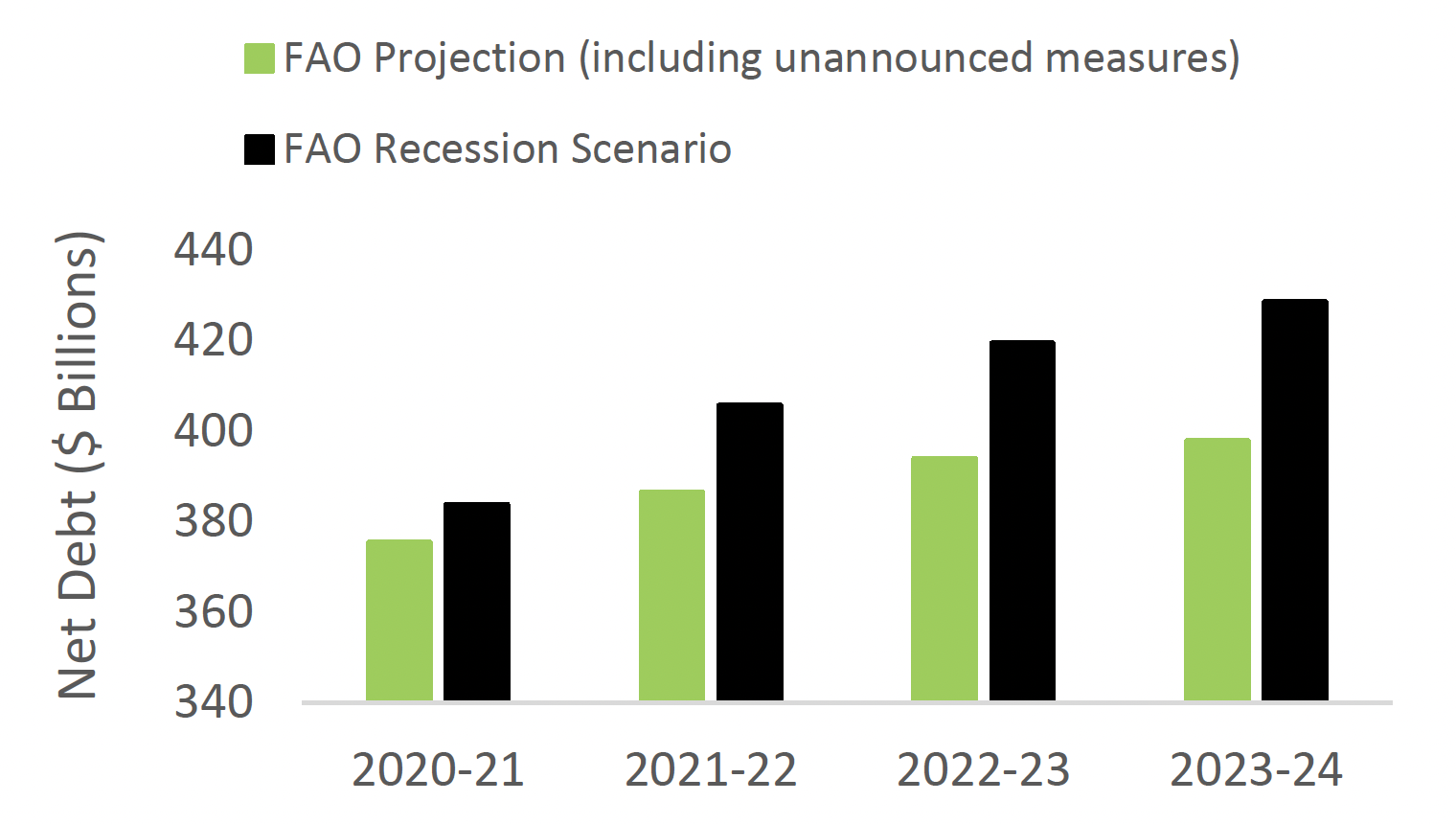

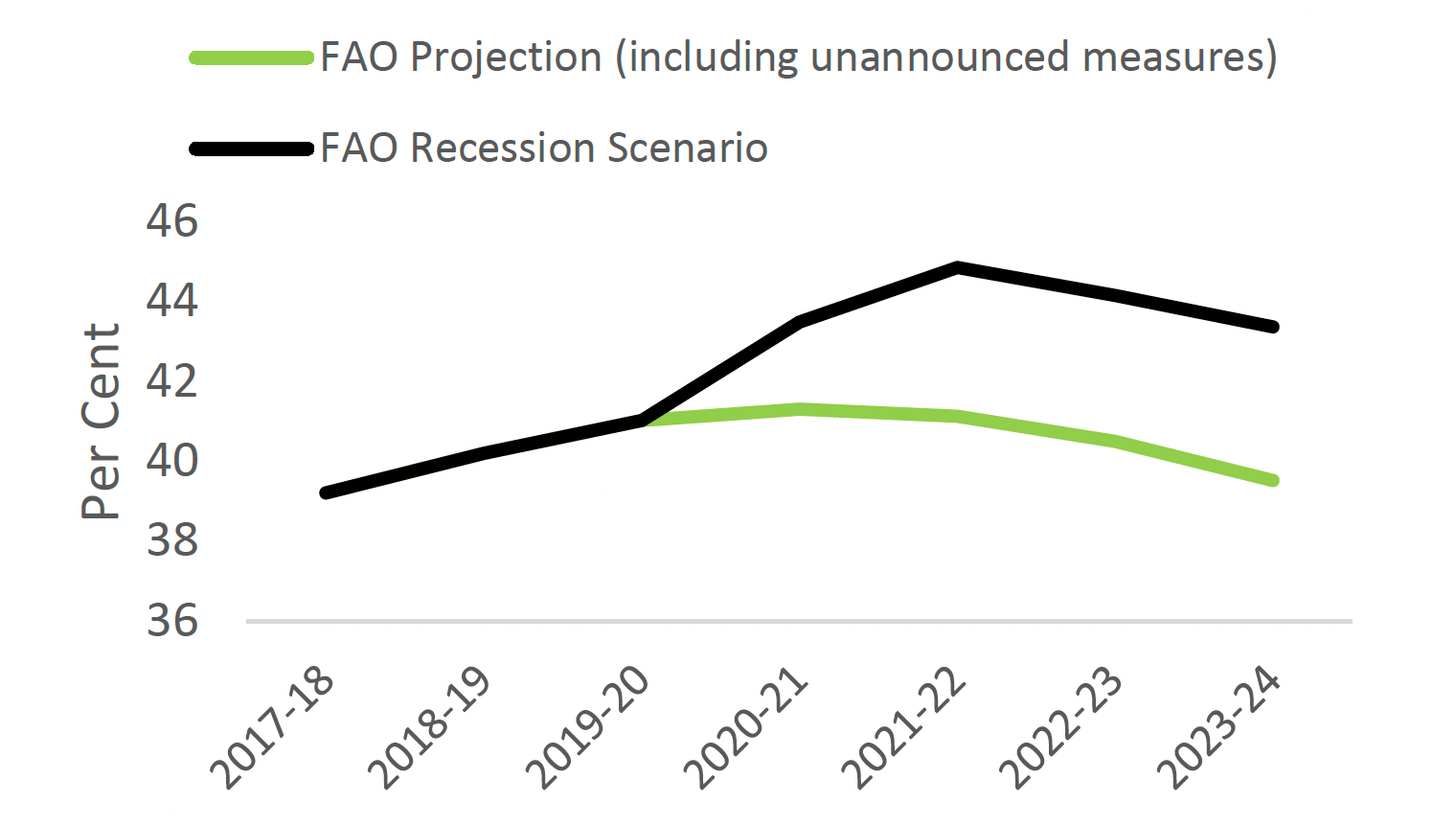

Higher deficits under the recession scenario would result in $8.3 billion more debt in 2020-21, rising to $30.7 billion by 2023-24. As a result of higher debt and slower economic growth, the net debt-to-GDP ratio would increase to 44.9 per cent by 2021-22. While the FAO projects modest improvements over the following two years, Ontario’s net debt-to-GDP ratio would be expected to remain well above the government’s ceiling of 40.8 per cent over the outlook.

Net debt $31 billion higher

by 2023-24

Source: FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows Ontario’s net debt from 2020-21 to 2023-24 under the FAO projection (including unannounced measures) and the FAO recession scenario. Compared to the FAO projection, Ontario’s net debt under the FAO recession scenario is higher by $8.3 billion in 2020-21, rising to $30.7 billion by 2023-24.

Net debt-to-GDP ratio remains 4 per cent higher

Source: FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows Ontario’s net debt-to-GDP ratio under the FAO projection (including unannounced measures) and the FAO recession scenario. Under the FAO recession scenario, Ontario’s net debt-to-GDP ratio would increase to 44.9 per cent by 2021-22, with modest improvements over the following two years.

Based on the FAO’s analysis, the government’s fiscal plan is vulnerable to an economic downturn. Even in the relatively moderate recession assumed for this analysis, Ontario’s budget deficit would be expected to increase significantly, exceeding $16.5 billion (or 1.8 per cent of GDP[19]) in 2021-22. While the deficit would be expected to improve as the economy recovers, the accumulated debt would remain on the provincial balance sheet as a legacy of the recession. Given the significant deterioration in the Province’s fiscal position, the government’s commitments to balance the budget by 2023-24 and limit Ontario’s net debt-to-GDP ratio to a maximum of 40.8 per cent would likely not be achieved.

Footnotes

[1] See page 23 in the 2019 Spring Economic and Budget Outlook (EBO) for the FAO’s baseline budget balance projection including and excluding unannounced measures.

[2] This scenario is consistent with the views of a number of economic forecasters, who believe that the next downturn in the United States or Canada will be mild compared to past recessions. For example, see Yield curve not the only recession indicator, Capital Economics, US Economics Update, March 2019 and TD Economics, Canadian ‘Solo’ Recession Risk: Rhetoric vs Reality, March 2019.

[3] Beginning in 2021-22, the 2019 Ontario Budget incorporates provisions for unannounced revenue reductions and spending measures. See pages 15 and 19 in the 2019 Spring EBO for more details.

[4] According to Analyzing and Managing Fiscal Risks – Best Practices, International Monetary Fund, June 2016, fiscal risk reports “can help ensure sound fiscal public finances and macroeconomic stability”. A number of legislative budget offices have begun to produce such reports, including the UK’s Office of Budget Responsibility.

[5] US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc., Public Information Office.

[6] For more historical details on Canadian recessions, see Turning Points: Business Cycles in Canada since 1926, CD Howe, 2012.

[7] The Impact of US-China Trade Tensions, Eugenio Cerutti, Gita Gopinath and Adil Mohommad, International Monetary Fund, May 2019.

[8] Wall Street Warns of Mounting Recession Risk From Trade War, Will Mathis and Enda Curran, Bloomberg, June 2019.

[9] Many experts view that the next downturn in the United States or Canada will be mild compared to past recessions. For example, see Yield curve not the only recession indicator, Capital Economics, US Economics Update, March 2019 and Canadian ‘Solo’ Recession Risk: Rhetoric vs Reality, TD Economics, March 2019.

[10] In contrast, in the 2019 Spring EBO, the FAO projected real GDP would grow by 1.5 per cent in 2020, and by an average of 1.6 per cent over the following four years.

[11] The base case projection is the FAO’s economic outlook in the 2019 Spring EBO.

[12] Based on past experiences, corporate profits typically decline steeply during recessions, but post quicker recoveries than other sectors of the economy. Accordingly, the FAO assumes that corporate profits would decline by 11 per cent in 2020 and then fully recover by 2023.

[13] In their most recent Financial System Review, the Bank of Canada included elevated corporate indebtedness in Canada as a key vulnerability for the economy.

[14] If U.S. Economy Hits Trouble, It Won’t Be Like 2008, Conor Sen, Bloomberg, June2019.

[15] In the FAO’s baseline projection, unannounced measures in the 2019 budget plan are excluded, as these measures are not reflected in current legislation and have not been formally proposed by the government.

[16] For historical examples, see A Review of Global Fiscal Stimulus, International Labour Organization and International Institute for Labour Studies, 2011; Canada’s Economic Action Plan Year 2: Budget Speech 2010: Leading the Way on Jobs and Growth, The Honourable James M. Flaherty, P.C., M.P., 2010; World Economic and Financial Surveys: Regional Economic Outlook: Western Hemisphere: Taking Advantage of Tailwinds, International Monetary Fund, 2010; Budget 2016: The Alberta Jobs Plan, Government of Alberta, 2016.

[17] Based on an analysis of previous recessions, the tax revenue generated from a given economic base (i.e. the tax yield from labour income or corporate profits) declines significantly during recessions. This is particularly the case for corporate income tax revenues during and following recessions due to provisions in the tax system. As a result, the FAO assumed that tax yields from labour income and corporate profits would decline during the recession, leading to a more pronounced decline in tax revenue compared to the decline in incomes.

[18] Importantly, if the government were to choose to implement additional fiscal stimulus measures, the deficit would deteriorate further.

[19] In 2009-10, Ontario’s deficit was 3.2% of GDP.