Update on Ontario’s Credit Rating

Key Points

- Ontario’s debt is rated by four principal international credit rating agencies[1], based on their assessments of the province’s economic and financial outlook and future risks.[2] These credit ratings represent the agencies’ opinions on the ability of Ontario to meet its debt-related financial obligations.

- Ontario benefits from a strong, investment-grade credit rating.[3] However, Ontario’s credit rating ranks in the middle of the pack compared to the other provinces, despite having the largest economy.

- Ontario’s credit rating has been reaffirmed this year by all four agencies. However, both Moody’s and Fitch have revised their rating outlook for Ontario’s debt from stable to negative, reflecting their assessment of the province’s increased credit risk.

- While Ontario’s rating remained unchanged, the four agencies cited several concerns regarding Ontario’s credit outlook, including the province’s high and rising debt burden, the projection of on-going deficits, and the risk of a future economic downturn.

- Over the next three years, the Province will need to refinance $75.2 billion in maturing debt.[4] New investments in capital assets along with any funding needed to finance budget deficits will further add to province’s borrowing requirements. A credit rating downgrade could increase the cost of this future borrowing, placing additional pressure on Ontario’s budget.

Ontario’s Credit Rating is Strong, but Concerns Remain

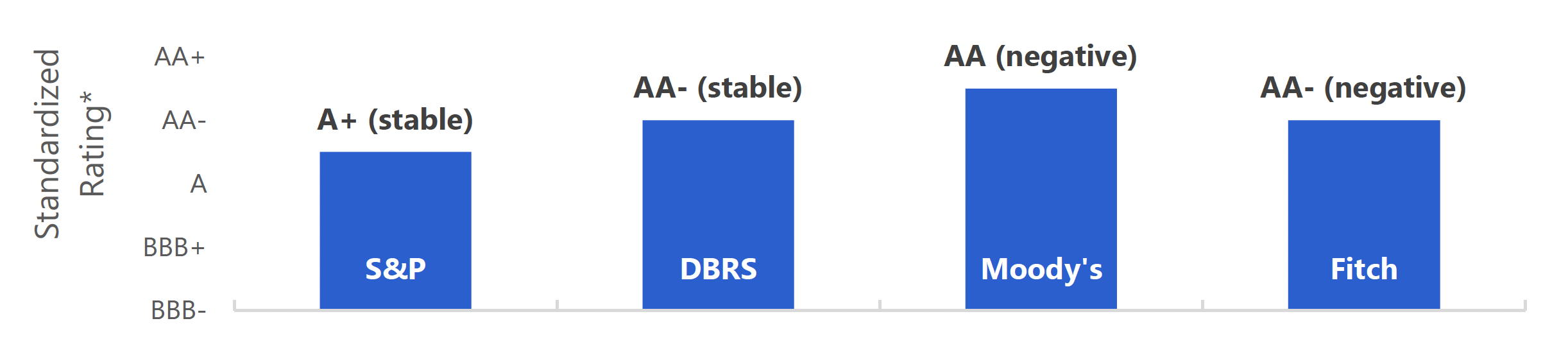

Based on a standardized scale[5], Ontario’s debt is currently rated between AA (3rd highest rating) by Moody’s and A+ (5th highest rating) by S&P. In general, the agencies rate Ontario as an ‘extremely strong’, investment-grade borrower. While all four agencies have reaffirmed their previous ratings[6], two agencies (Moody’s and Fitch) have changed their outlooks from stable to negative.[7]

The four agencies note that Ontario’s credit quality is supported by a number of key strengths including a large, diversified economy, a high degree of fiscal flexibility[8] and well-established access to domestic and international capital markets.

However, the agencies also identified several challenges regarding Ontario’s credit rating, including the province’s high and rising debt burden and the decision in the 2018 Budget to return to large budget deficits going forward. The agencies also expressed concern over the significant risks facing the province’s economy. These risks are discussed in more detail below.

Ontario’s 2018 Credit Ratings

* Based on a standardized scale that includes 10 levels for investment-grade debt. See Appendix The Agencies’ Credit Rating Scales.

Note: Outlooks are in parentheses. See Appendix Background on Credit Rating Agencies for discussion on outlooks.

Source: S&P, DBRS, Fitch, Moody’s and FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows the standardized credit rating for Ontario for each credit rating agency. Ontario has a A+ rating with a stable outlook from S&P, an AA- rating with a stable outlook from DBRS, an AA rating with a negative outlook from Moody’s and an AA- rating with a negative outlook from Fitch.

Growing Debt Burden

With about $350 billion in total debt, Ontario is the most indebted Canadian province and also posts one of the highest debt-to-revenue ratios compared to global peers.[9] Ontario’s debt burden is projected to rise as the province borrows to fund new investments in capital assets. Debt could further be increased if additional borrowing is needed to finance budget deficits. S&P, DBRS and Moody’s have all warned that Ontario’s rising debt could trigger a downgrade.[10]

Ontario’s Return to Budget Deficits

In the 2018 Budget, the previous government projected budget deficits over the medium-term, reversing a prior commitment of achieving and maintaining balanced budgets. While the new government has indicated that they will target a return to balanced budgets “on a responsible timeframe”[11], most agencies expect budget deficits to continue over the next several years based on the government’s election platform.[12] More moderate economic growth is expected to lead to slower revenue growth, which could be further impacted by the promised tax reductions of the new government. At the same time, restrained growth in program spending over the last number of years combined with the province’s growing population and its education and health care responsibilities could increase the challenge of reducing spending going forward.[13] Interest expense is also expected to increase as borrowing increases and interest rates rise, putting further pressure on Ontario’s budget.

The extent of future budget deficits is expected to be clarified when the government releases its first detailed fiscal outlook in the upcoming 2018 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review. Fitch and DBRS have warned that an extended return to deficits[14] or deficits worse than those proposed in the 2018 Budget[15] could likely lead to a downgrade.

Economic Risks Increase

The agencies highlighted the significant economic risks currently facing the province, including heightened trade tensions with the United States, high levels of household debt and the impact of rising interest rates on residential investment and consumer spending.

The agencies are also critical of the government’s decision to return to budget deficits, at a time when the economy is at or near the peak of the business cycle. Given Ontario’s current fiscal situation, a negative economic shock, which adversely impacts revenues, would put additional pressure on the key debt metrics[16] that agencies use to judge Ontario’s credit health. A dramatic deterioration in these metrics could lead to a ratings downgrade.

Ontario’s ‘Middle of the Pack’ Credit Rating

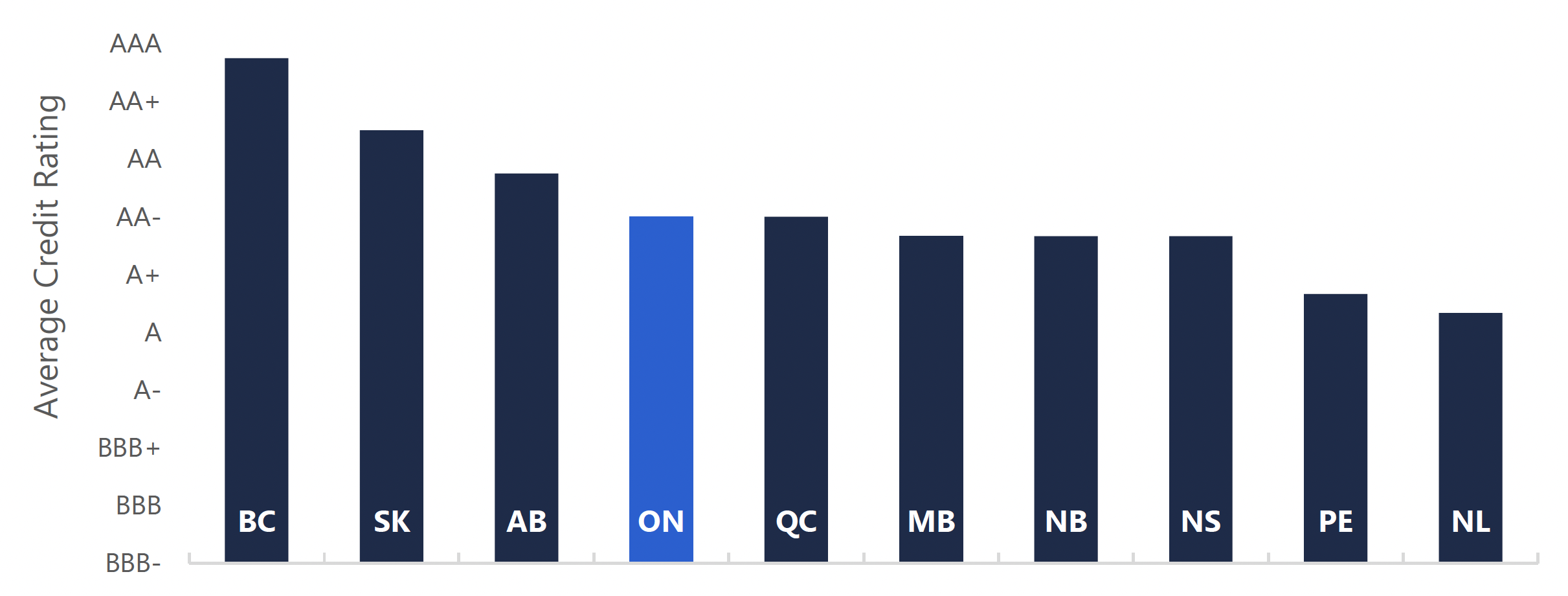

Canadian provinces all have very strong, investment-grade credit ratings. Ontario’s rating lies in the middle of the provincial pack, matching that of Quebec, but lower than BC, Saskatchewan and Alberta and higher than the eastern provinces and Manitoba.

Average Credit Rating by Province[17]

Source: S&P, DBRS, Fitch, Moody’s and FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows the average credit rating by province. The chart shows British Columbia has the highest rating, followed by Saskatchewan then Alberta. Ontario is tied with Quebec for the fourth highest rating. Ontario and Quebec are follow by Manitoba, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia who all have the same average rating. Prince Edward Island has the second lowest rating, followed by Newfoundland and Labrador, which has the lowest credit rating.

Credit Ratings and Provincial Borrowing Costs

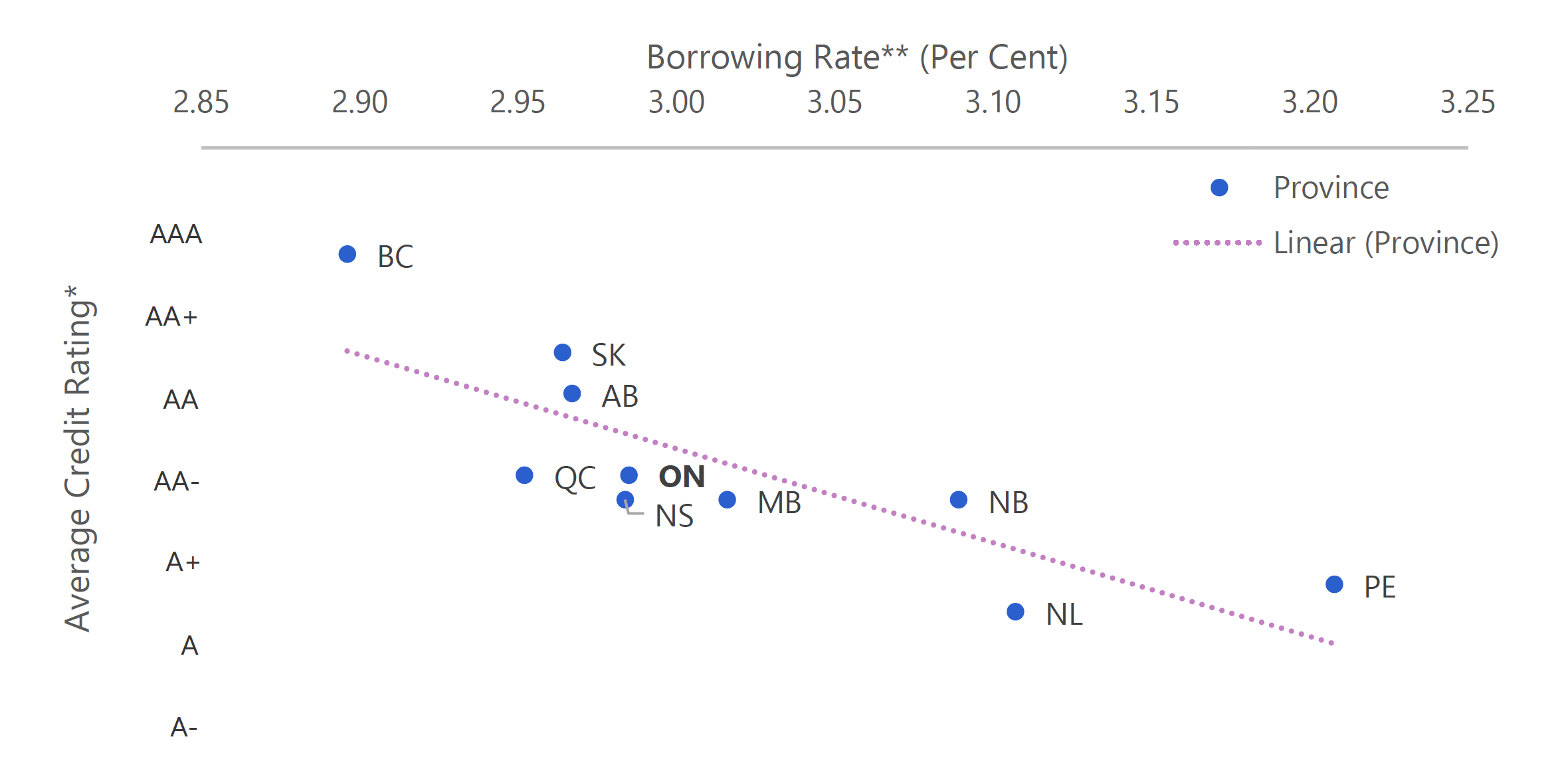

Credit ratings are used by investors to assess the credit risk of a borrower. Higher credit ratings are typically reflected in lower borrowing costs. A provincial comparison shows the negative correlation between credit ratings and bond yields. Like its credit rating, Ontario’s cost of borrowing lies in the middle of the provincial pack. British Columbia has the highest credit rating and benefits from the lowest borrowing cost, while Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador, with the lowest credit ratings, have the highest borrowing costs.

Bond Yields Rise as Credit Rating Decreases

* See footnote 17 for a description of average rating.

** Borrowing rates are for 10-year bonds.

Note: Borrowing rates and credit ratings as of September 11, 2018.

Source: CanDeal, S&P, DBRS, Fitch, Moody’s and FAO.

Accessible version

This chart shows the average credit rating by province compared to the provinces borrowing rate. The chart shows a negative correlation between credit ratings a borrowing rates, that is, the lower the credit rating the higher the borrowing rate and vice versa. British Columbia has both the highest credit rating and the lowest borrowing rate. Prince Edward Island has the second lowest credit rating and the highest borrowing rate. Newfoundland and Labrador has the lowest credit rating and the second highest borrowing rate. Ontario’s has fourth highest credit rating (tied with Quebec) and the fifth lowest borrowing rate.

While academic studies have shown that borrowing costs do react to announcements of credit downgrades and negative outlooks,[18] it is difficult to distinguish the impact of the credit rating change itself from the change in the underlying economic and fiscal environment.[19] Market participants rely on a broad range of information to guide their investment decisions in addition to an entity’s credit rating. Much of this information is available publicly and is used by the agencies in their credit rating assessments.[20] As a result, credit ratings supplement this public information.[21]

Appendix

Background on Credit Rating Agencies

Credit rating agencies are private, for-profit companies which assign a credit rating to the debt of governments or corporations. The credit rating is an assessment of the borrower’s credit risk and reflects the borrower’s ability to make interest payments as well as repay the original debt. A credit rating is a relative measure of the likelihood of default by a borrower, based on economic and financial forecasts and an assessment of future developments and risks. The factors that go into a government’s credit rating can be divided into five broad categories[22]:

- economic conditions;

- fiscal performance;

- financial and debt position;

- management quality and institutional strengths; and

- influence of intergovernmental relationships and fiscal arrangements.

Rating agencies also typically assign “outlooks” to credit ratings. The outlook of a credit rating indicates the likely direction of a borrower’s credit rating over the next two years. An outlook can either be stable, negative or positive. A stable outlook indicates that the borrower’s rating, all else equal, is unlikely to change in the short-term, while a negative or positive outlook indicates that the rating is likely to be lowered or raised over the same period. A change in a credit rating outlook does not necessarily indicate a change in the current credit rating.

Debt issuers (governments and corporations) are charged a fee by credit rating agencies to issue a credit rating, while investors (purchasers of debt) also pay a fee to access credit reports. The critical importance of an agency’s reputation ensures that credit rating agencies strive to provide an unbiased and accurate assessment of credit risk.

The main motivation for a debt issuer to acquire a credit rating is that the rating helps the issuer raise funds in capital markets. Receiving an investment-grade credit rating is valuable as it attracts and expands the number of investors willing to lend to the issuer in addition to substantially lowering the cost of borrowing.

| Province | S&P | DBRS | Moody’s | Fitch | Average Rating* (1 = highest rating) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | AAA (stable) | AA high (stable) | Aaa (stable) | AAA (stable) | 1.3 |

| Alberta | A+ (stable) | AA (negative) | Aa1 (negative) | AA (stable) | 3.3 |

| Saskatchewan | AA (stable) | AA (stable) | Aaa (stable) | AA (stable) | 2.5 |

| Manitoba | A+ (stable) | A high (stable) | Aa2 (stable) | 4.3 | |

| Ontario | A+ (stable) | AA low (stable) | Aa2 (negative) | AA- (negative) | 4.0 |

| Quebec | AA- (stable) | A high (stable) | Aa2 (stable) | AA- (stable) | 4.0 |

| New Brunswick | A+ (stable) | A high (negative) | Aa2 (stable) | 4.3 | |

| Nova Scotia | A+ (positive) | A high (stable) | Aa2 (stable) | 4.3 | |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | A (stable) | A low, (stable) | Aa3 (negative) | 5.7 | |

| Prince Edward Island | A (stable) | A low (positive) | Aa2 (stable) | 5.3 |

| Rating Description | Credit Quality | S&P | DBRS | Moody’s | Fitch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long Term | Long Term | Long Term | Long Term | Ranking | ||

| Investment-grade | Extremely Strong | AAA | AAA | Aaa | AAA | 1 |

| AA+ | AA high | Aa1 | AA+ | 2 | ||

| AA | AA | Aa2 | AA | 3 | ||

| AA- | AA low | Aa3 | AA- | 4 | ||

| Very Strong | A+ | A high | A1 | A+ | 5 | |

| A | A | A2 | A | 6 | ||

| A- | A low | A3 | A- | 7 | ||

| Strong | BBB+ | BBB high | Baa1 | BBB+ | 8 | |

| BBB | BBB | Baa2 | BBB | 9 | ||

| BBB- | BBB low | Baa3 | BBB- | 10 | ||

| Non Investment-grade | Speculative | BB+ | BB high | Ba1 | BB+ | 11 |

| BB | BB | Ba2 | BB | 12 | ||

| BB- | BB low | Ba3 | BB- | 13 | ||

| B+ | B high | B1 | B+ | 14 | ||

| B | B | B2 | B | 15 | ||

| B- | B low | B3 | B- | 16 | ||

| CCC | CCC | Caa | CCC | 17 |

Footnotes

[1] The four credit rating agencies are Moody’s Investors Service (Moody’s), S&P Global Ratings (S&P), DBRS Limited (DBRS) and Fitch Ratings (Fitch). The agencies review the province’s credit ratings annually and typically publish an update on their view of the Province’s finances and credit quality, based on the government’s latest financial reports or statements.

[2] See Appendix Background on Credit Rating Agencies for additional discussion on rating agencies.

[3] Technically, the agencies refer to Ontario’s debt as ‘extremely’ strong. See Appendix The Agencies’ Credit Rating Scales for credit quality of the ratings.

[4] Summary of Borrowing Program and Medium-Term Outlook, 2018 Ontario Budget.

[5] See Appendix The Agencies’ Credit Rating Scales for a standardized scale.

[6] Moody’s and DBRS released their updates in April after the 2018 Ontario Budget, while S&P and Fitch released theirs after the 2018 Ontario election.

[7] See Appendix Background on Credit Rating Agencies for discussion on outlooks.

[8] Canada’s inter-governmental system provides significant fiscal flexibility to provinces. Provinces have significant freedom to determine their own revenues and expenses. Additionally, Canadian provinces have a high likelihood of receiving support from the federal government in the event of a potential default.

[9] Moody’s Investors Services. Moody’s changes outlook to negative on Ontario’s Aa2 ratings. April 17, 2018.

[10] DBRS noted that the increase in debt could be in the context of a downturn in the economy or a deterioration in the budgetary outlook beyond what was proposed in the 2018 budget. S&P warned that if the province’s tax-supported debt burden increased toward 270 per cent of operating revenues, this could cause a downgrade. They suggested this could happen if an economic shock lowered revenues, which coupled with unsustainable fiscal policies, produced after-capital deficits financed by debt. Moody’s indicated that if the province’s net direct and indirect debt rises above 240 per cent of revenues this could lead to a downgrade.

[11] Ontario (2018). A Government for the People – Speech from the throne: July 12, 2018.

[12] Moody’s did not release a public statement after the election. Although, Michael Yake of Moody’s communicated to the FAO that the election had not altered Moody’s credit rating of Ontario and indicated Moody’s is waiting for a clear indication of the fiscal path the government will take. For DBRS’ post-election commentary see Ontario’s 2018 Provincial Election: Credit Neutral, Long-Term Risks Remain, DBRS Limited, June 8, 2018.

[13] S&P Global Ratings. Province of Ontario Issuer Credit Rating Affirmed At ‘A+’ Following Election; Outlook Remains Stable. June 25, 2018. The FAO has also identified Ontario government spending pressure as a key fiscal risk. See Spring 2018 Economic and Budget Outlook report and the commentary Assessing Ontario Government Employment and Wage Expense.

[14] Fitch Ratings. Fitch Affirms Province of Ontario, Canada’s IDR at ‘AA-‘; Outlook Revised to Negative. June 15, 2018.

[15] DBRS Limited. DBRS Confirms Province of Ontario at AA (low) and R-1 (middle), Stable Trends. April 24, 2018. See footnote 10.

[16] These metrics include the debt-to-revenue and interest expense-to-revenue ratios.

[17] The average rating is created by first translating each rating into a standardized rating and then converting all ratings to numerical values, 1 being the highest rating and 17 being the lowest rating (see Appendix The Agencies’ Credit Rating Scales for translation matrix), after which, the average numerical ranking is converted to letter rating. For example, Ontario’s rankings are 5, 4, 4 and 3 from S&P, DBRS, Fitch and Moody’s, respectively, for an average of 4, which translates into a AA- letter rating. Additionally, average ratings do not reflect outlooks, only credit ratings.

[18] Steiner, M. & Heinke, V.G. (2001). Event Study Concerning International Bond Price Effects of Credit Rating Actions. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 6 (2), 139-57.

[19] Kliger, D & Sarig, O. (2000). The Information Value of Bond Ratings, Journal of Finance, 25(6), 2879–902.

[20] This information includes the five broad categories listed in the Appendix Background on Credit Rating Agencies. Many other factors are also important in determining borrowing costs including the time to maturity, the size of the bond or whether the bond is callable, among others. For further information see Cantor, R., Packer, F., Cole, K. (1997), Split Ratings and the Pricing of Credit Risk, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Research Paper No. 9711.

[21] Cantor R. & Packer, F. (1996). Determinants and Impacts of Sovereign Credit Ratings. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, 37-54.

[22] Liu, L & Tan, K.S. (2009). Subnational Credit Rating: A Comparative Review. World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper; no. WPS 5013.