1. Summary

- This report reviews Government of Ontario (the Province) spending trends from 1990-91 to 2023-24. The report also reviews trends in federal government transfers to Ontario and analyzes federal transfers as a share of provincial spending.

Ontario Government Spending Trends

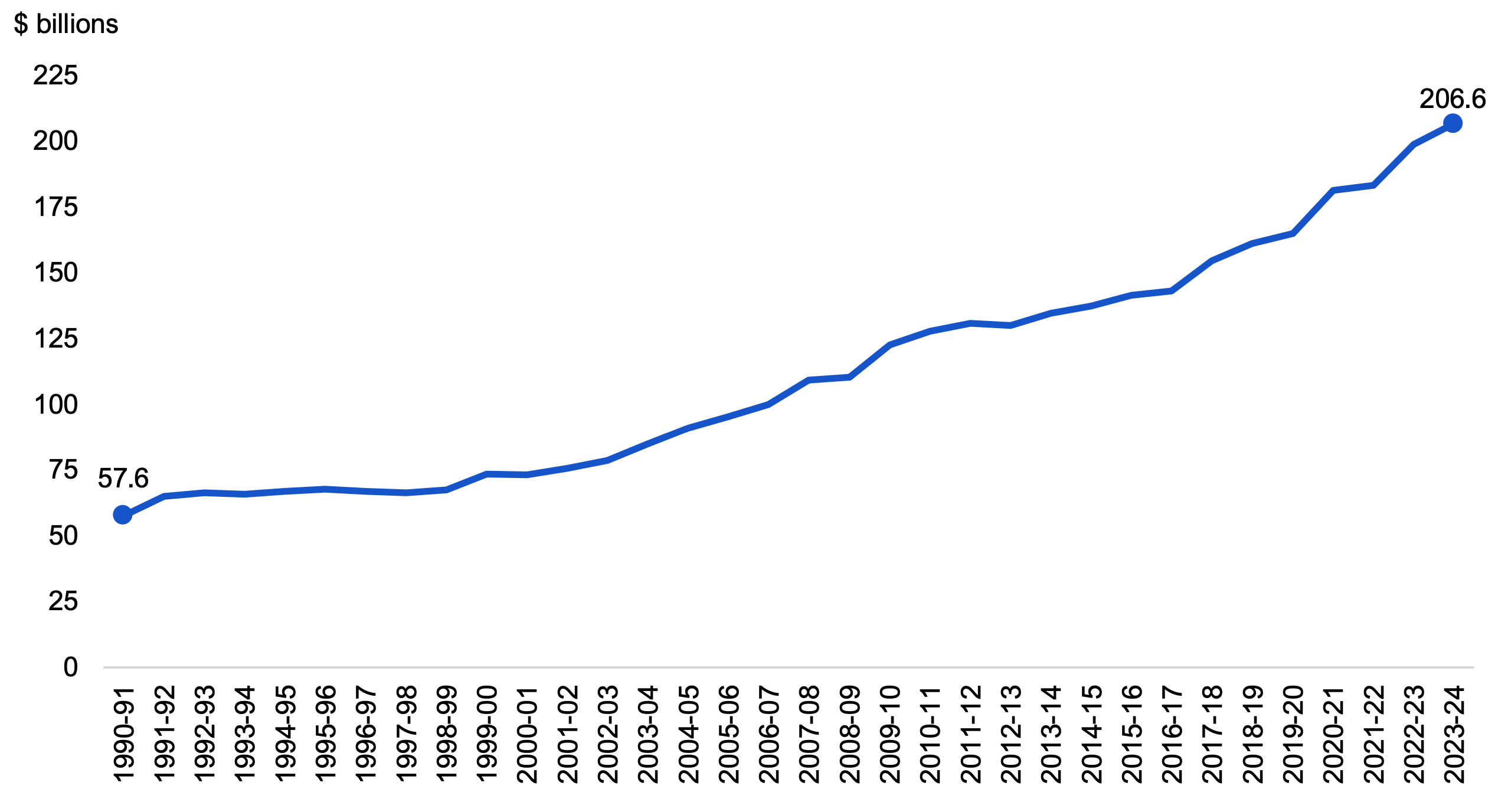

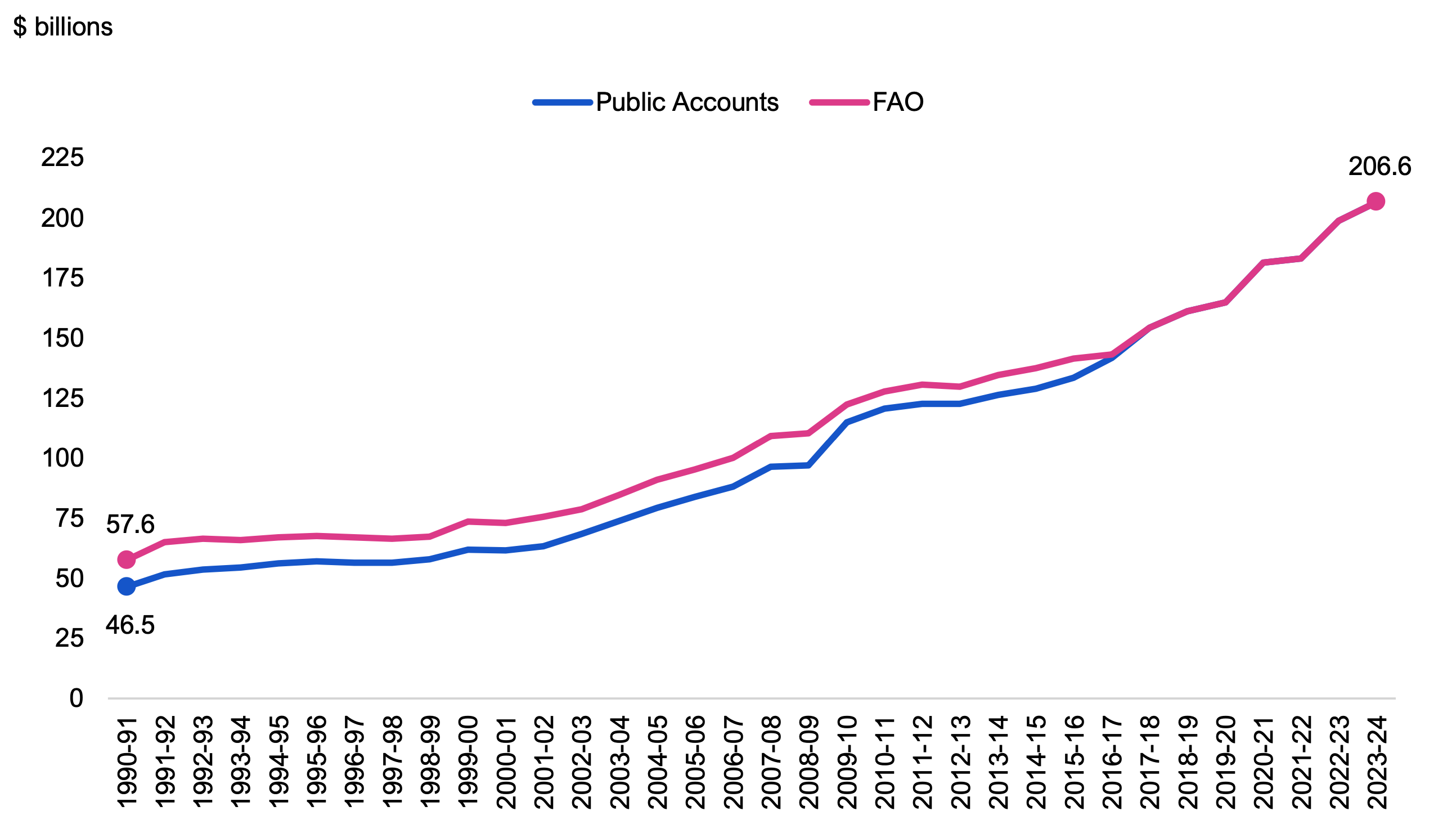

- In 2023-24, the Province spent a total of $206.6 billion, up from $57.6 billion in 1990-91, representing an average annual increase of 3.9 per cent, in nominal (not adjusted for inflation) dollars.

- Total nominal spending increased every year over this 34-year period, with the exception of five years: 1993-94, 1996-97, 1997-98, 2000-01 and 2012-13.

- Nominal government spending can obscure the true impact of government spending on service levels over time as it does not account for changes in Ontario’s population and inflation. Inflation increases the cost of providing public goods and services, while population growth drives up the demand for public services. Therefore, this report also reviews government spending on inflation-adjusted (i.e., real) and per capita terms.

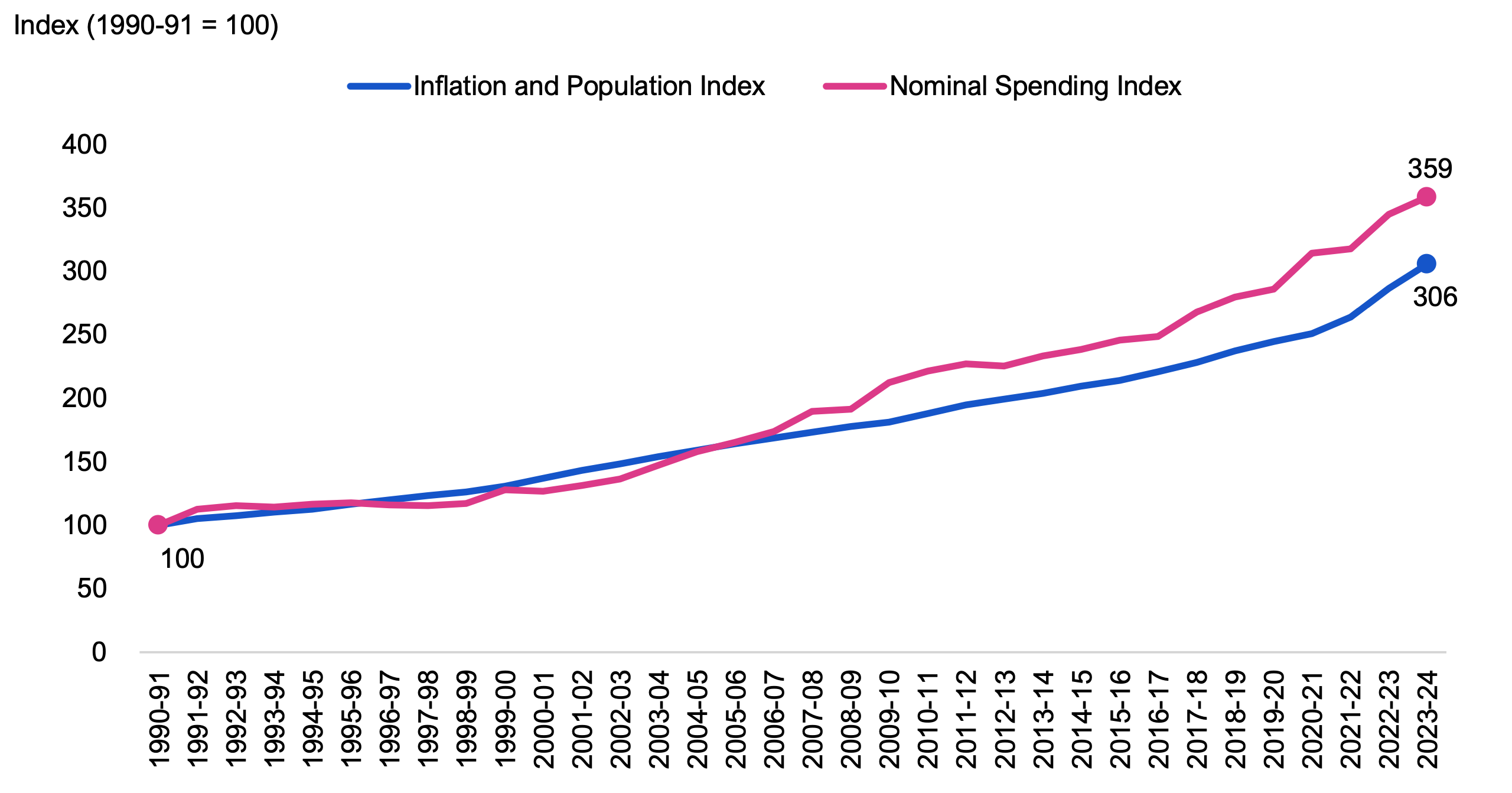

- Inflation and population growth have increased at a combined average annual rate of 3.4 per cent from 1990-91 to 2023-24.

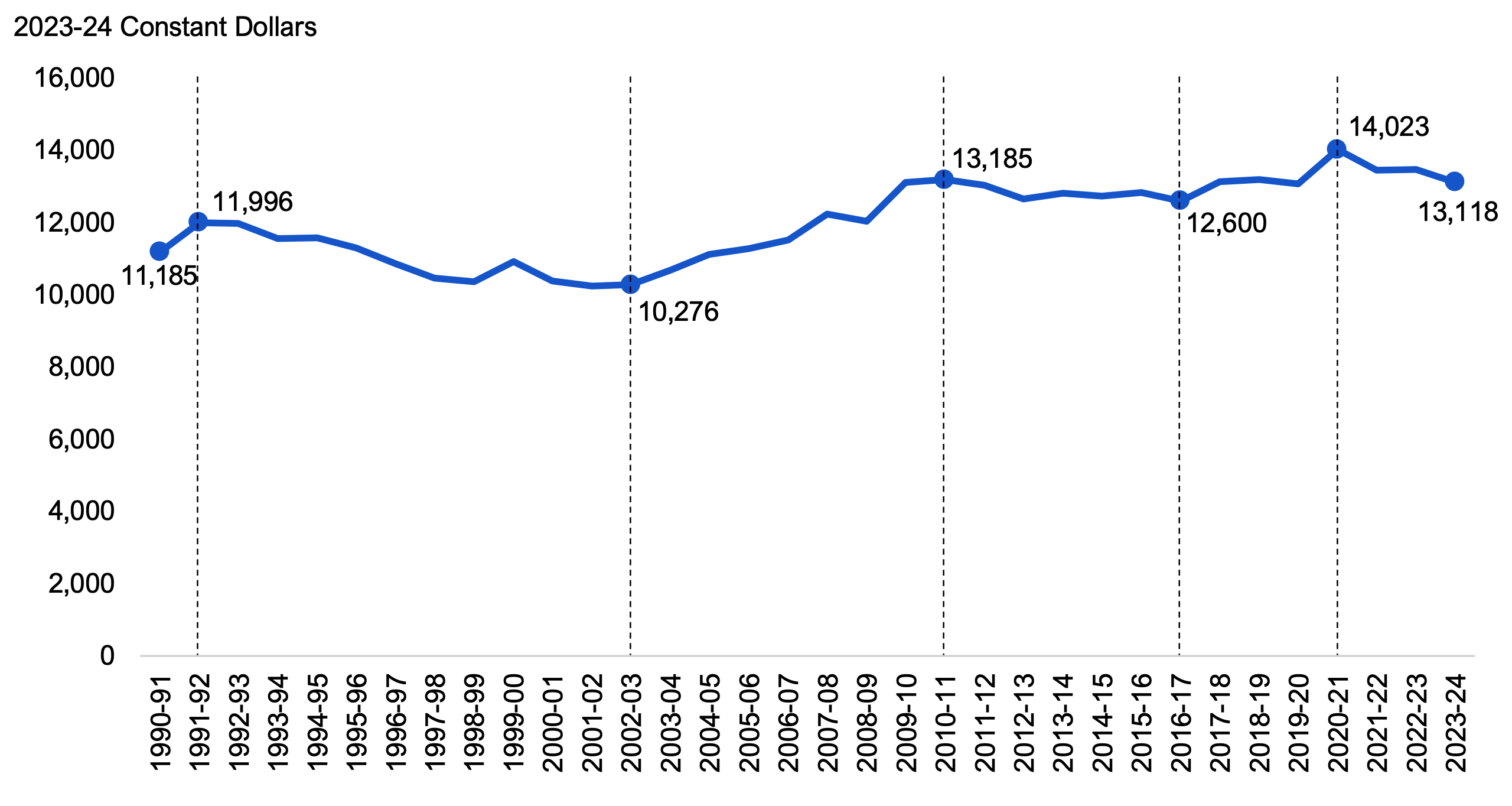

- Consequently, the Province’s real per capita spending has increased at an average annual rate of 0.5 per cent, from spending of $11,185 per person in 1990-91 to $13,118 per person in 2023-24.

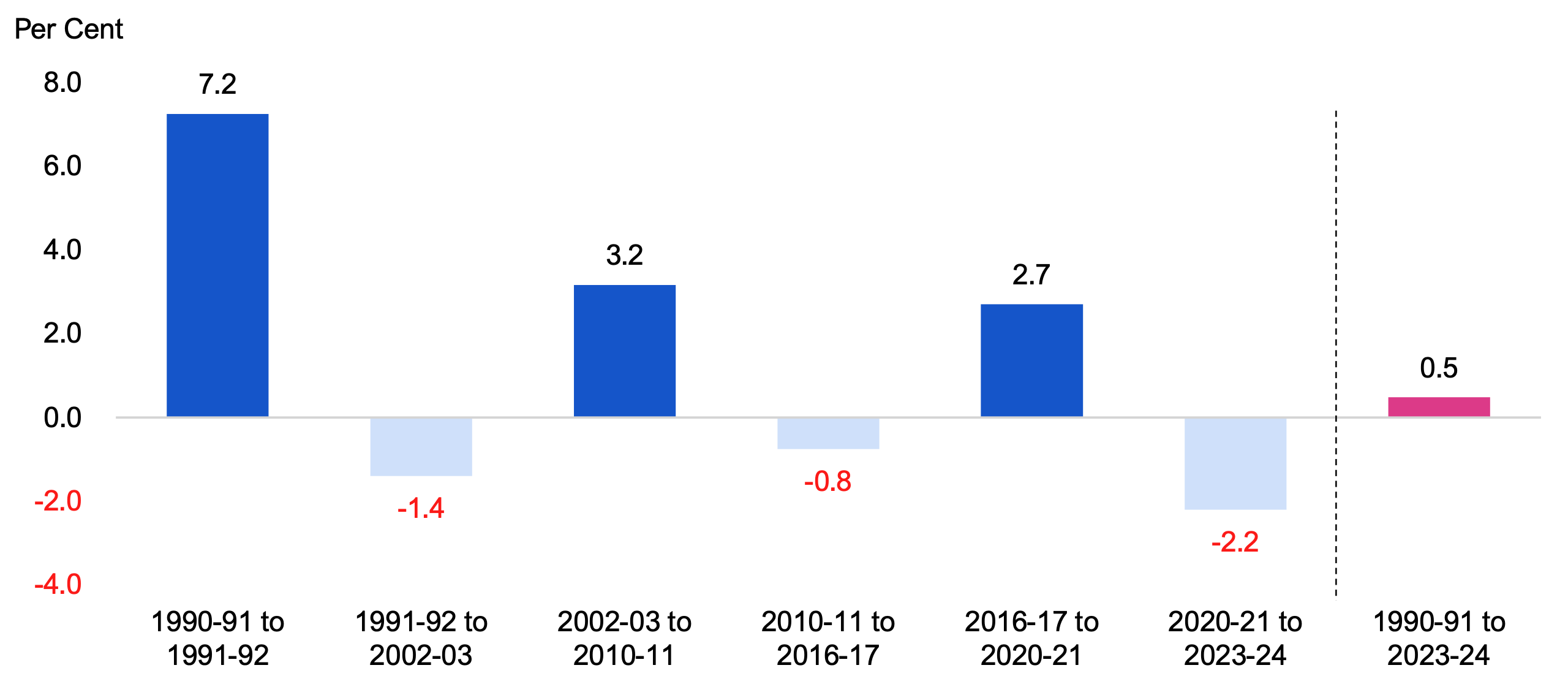

- Over the 34-year period, the FAO identified three periods of real per capita spending growth: one year from 1990-91 to 1991-92 (7.2 per cent growth); eight years from 2002-03 to 2010-11 (3.2 per cent average annual growth); and four years from 2016-17 to 2020-21 (2.7 per cent average annual growth).

- The FAO also identified three periods of real per capita spending declines: 11 years from 1991-92 to 2002-03 (-1.4 per cent average annual decline); six years from 2010-11 to 2016-17 (-0.8 per cent average annual decline); and three years from 2020-21 to 2023-24 (-2.2 per cent average annual decline).

- Another approach to analyzing government spending trends is to compare nominal government spending to nominal gross domestic product (GDP). As nominal GDP is the broadest measure of the tax base, this comparison provides insight into the size of government spending relative to the economy’s ability to pay.

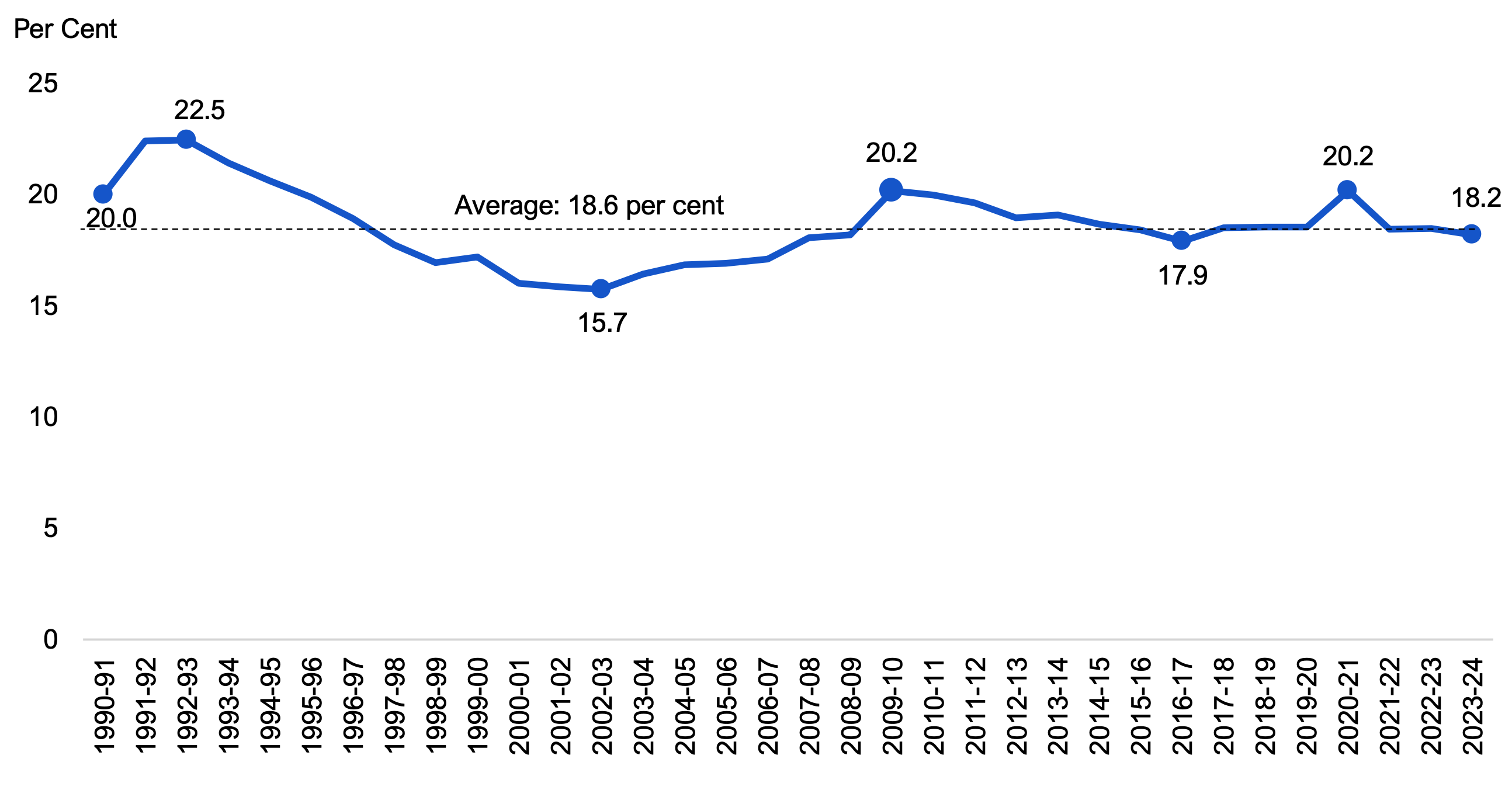

- Spending as a share of Ontario’s GDP averaged 18.6 per cent over the 34-year period and was 18.2 per cent in 2023-24.

- Spending as a share of GDP peaked during the 1990s recession (22.5 per cent in 1992-93), the 2008-2009 global financial crisis (20.2 per cent in 2009-10) and the COVID-19 pandemic (20.2 per cent in 2020-21).

- Spending as a share of GDP reached a low of 15.7 per cent in 2002-03, reflecting a period of spending restraint combined with a pickup in economic growth.

Spending Trends by Sector

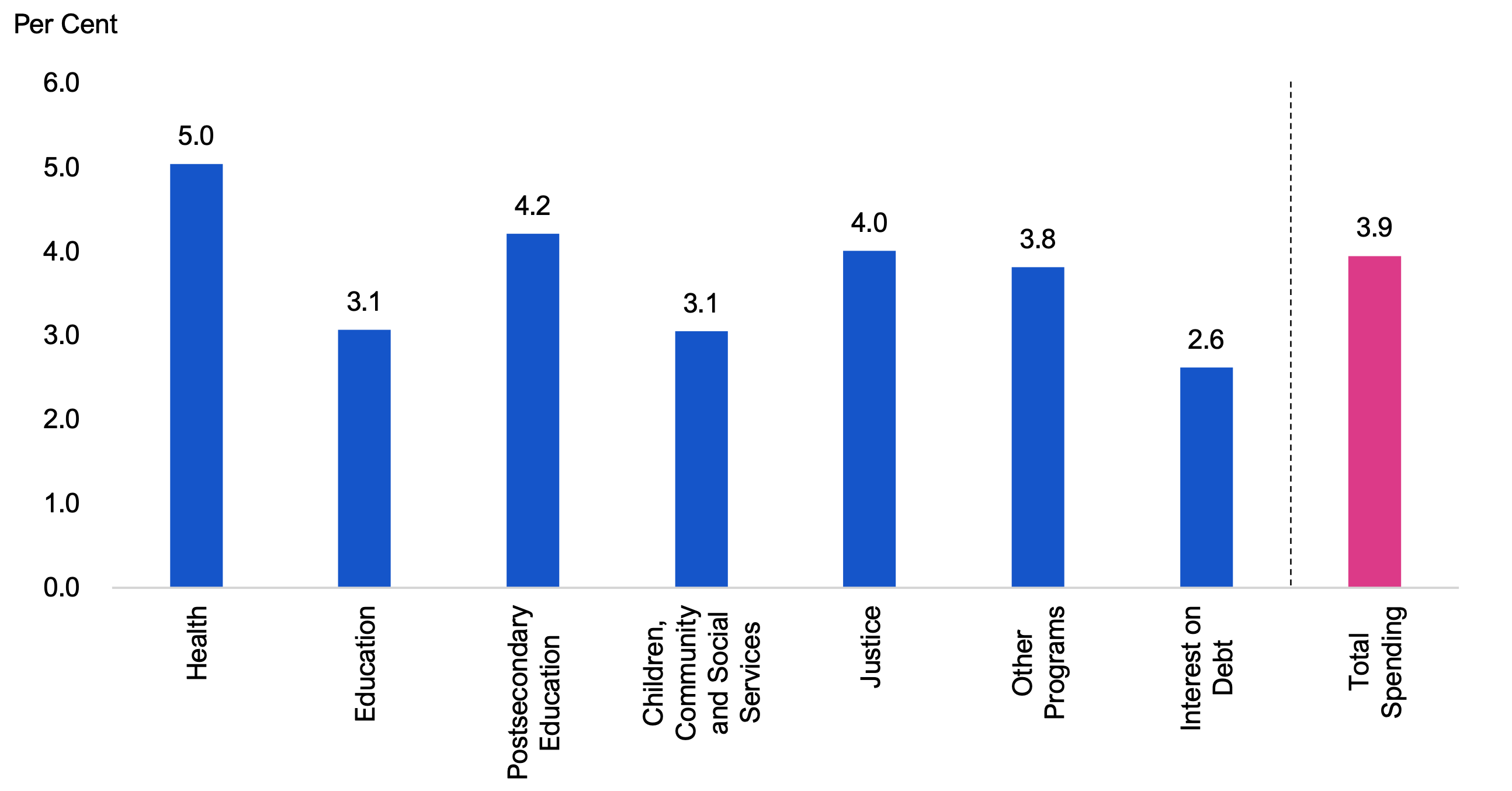

- The Province categorizes its spending into seven sectors: health; education; postsecondary education; children, community and social services; justice; ‘other programs’; and interest on debt. While total nominal spending growth averaged 3.9 per cent per year over the 34-year period, spending growth has varied by sector.

- Overall, three sectors, health (5.0 per cent), postsecondary education (4.2 per cent) and justice (4.0 per cent) experienced above average annual growth over the 34-year period, while four sectors, ‘other programs’ (3.8 per cent), children, community and social services (3.1 per cent), education (3.1 per cent) and interest on debt (2.6 per cent) experienced below average annual growth.

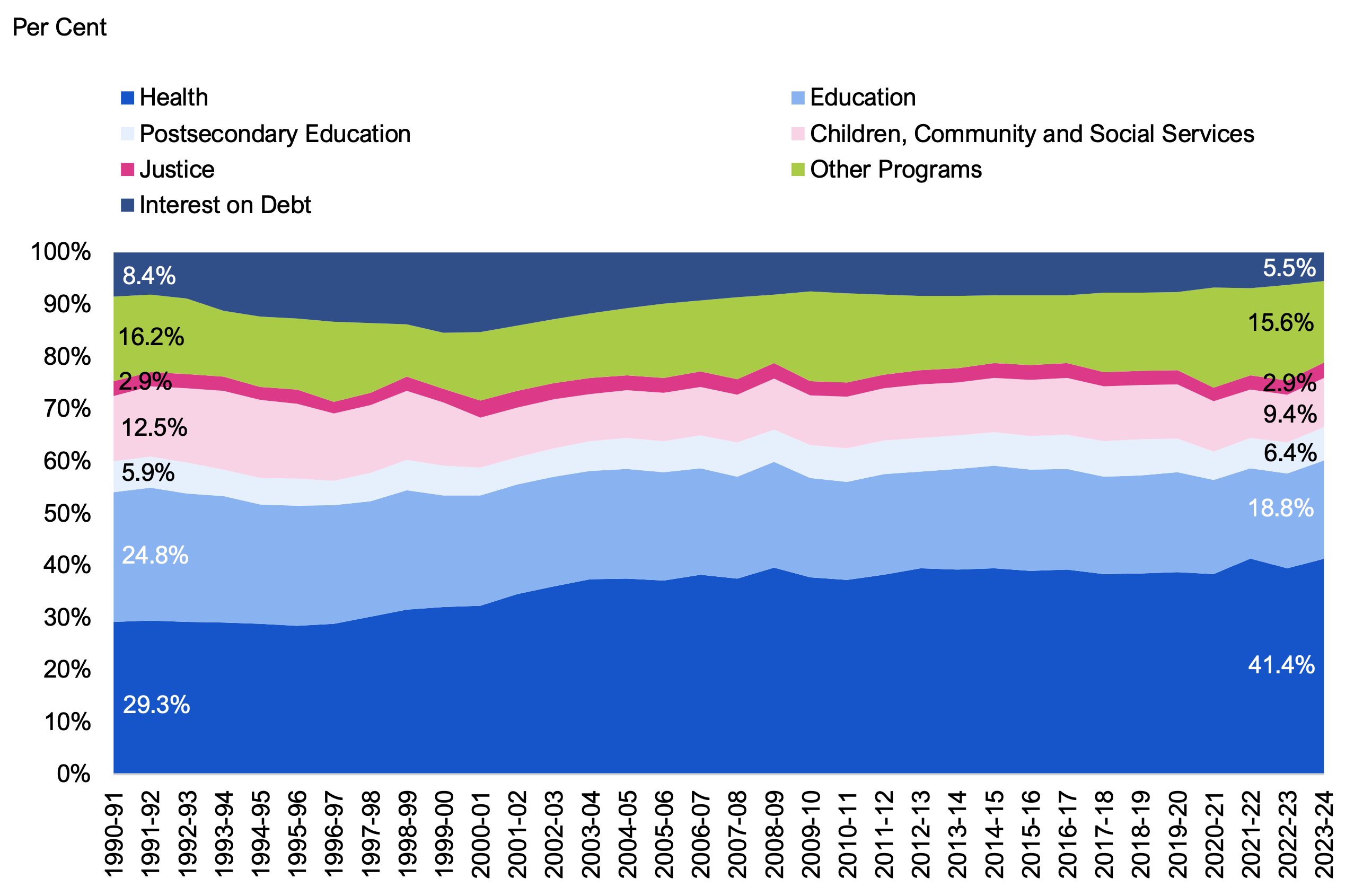

- The different spending growth rates have led to changes in each sector’s spending as a share of total spending:

- The health sector has been the largest spending sector throughout the 34-year period, while its share of total spending has steadily increased, from 29.3 per cent in 1990-91 to 41.4 per cent in 2023-24.

- The second largest spending sector over this period was education; however, education sector spending as a share of total spending has steadily declined, from 24.8 per cent in 1990-91 to 18.8 per cent in 2023-24.

- Spending on postsecondary education increased from 5.9 per cent of total spending in 1990-91 to 6.4 per cent in 2023-24.

- Children, community and social services spending decreased from 12.5 per cent of total spending in 1990-91 to 9.4 per cent in 2023-24.

- Justice sector spending as a share of total spending has remained relatively unchanged, at 2.9 per cent of total spending in both 1990-91 and 2023-24.

- ‘Other programs’ sector spending as a share of total spending has fluctuated over time, ranging between 10.0 per cent and 19.1 per cent of total spending. In 1990-91 ‘other programs’ spending was 16.2 per cent of total spending, while in 2023-24 it was 15.6 per cent of total spending.

- Interest on debt spending as a share of total spending increased from 8.4 per cent in 1990-91 to 15.4 per cent in 1999-00, and then steadily declined to 5.5 per cent of total spending in 2023-24.

- This report also reviews spending by sector adjusted for sector specific cost drivers to provide a better indication of the effect spending has on service levels over time. These cost drivers include inflation, population growth in the demographic served by the sector and, in the health sector, population aging.

- When adjusted for these cost drivers, from 1990-91 to 2023-24, four sectors experienced spending growth: health (0.9 per cent age-standardized real per capita average annual growth), education (0.7 per cent real per child/youth average annual growth), justice (0.5 per cent real per capita average annual growth) and ‘other programs’ (0.4 per cent real per capita average annual growth).

- Three sectors experienced spending declines: postsecondary education (-0.3 per cent real per student average annual decline), children, community and social services (-0.4 per cent real per capita average annual decline) and interest on debt (-0.8 per cent real per capita average annual decline).

- Chapters 5 through 11 review spending trends in the seven sectors in more detail, including trends in select service levels.

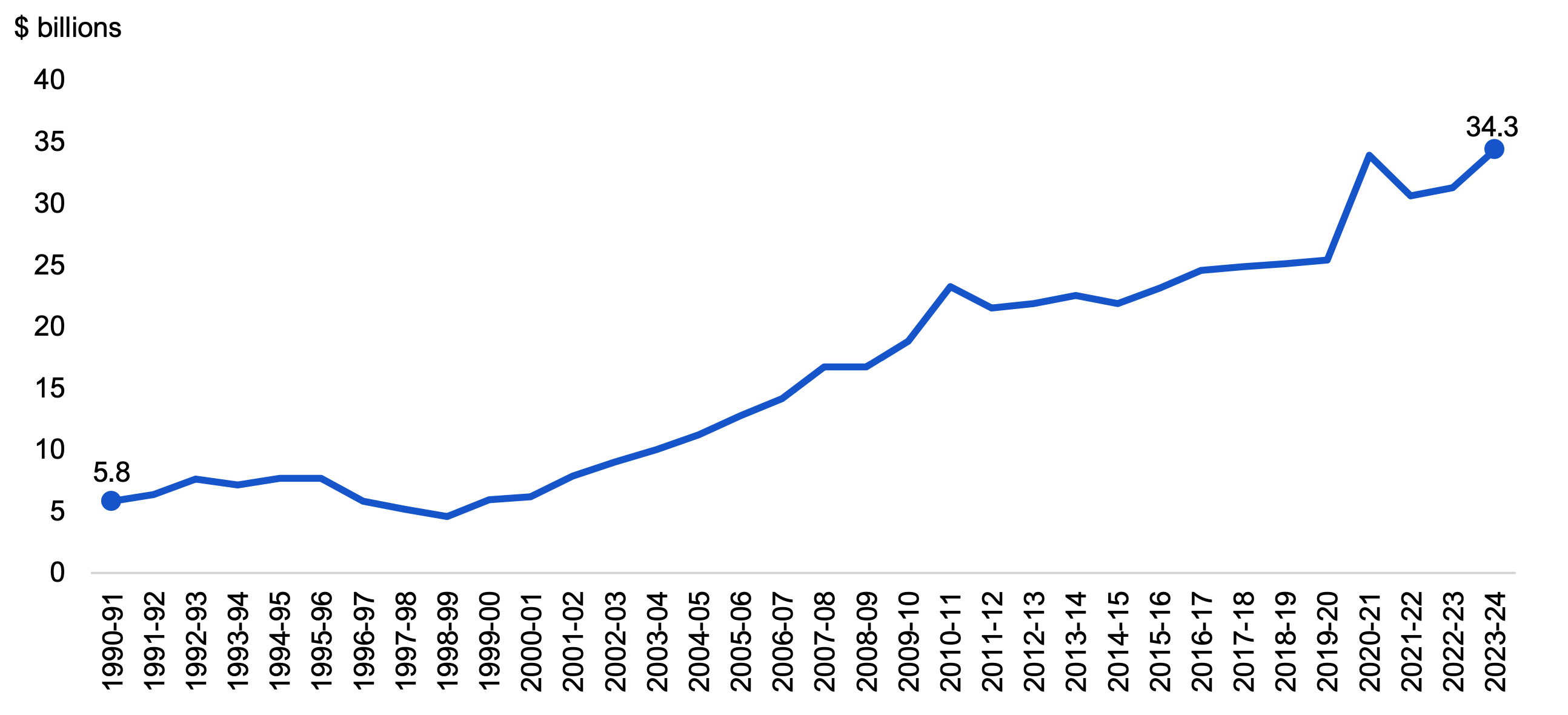

Trends in Federal Transfers to Ontario

- Transfers from the Government of Canada are an important source of provincial revenue that supports the Province in funding programs and services. Over the 34-year period, the majority of federal transfers to Ontario were provided under programs intended to help finance provincially run health care, social assistance and postsecondary education programs.

- The FAO estimates that transfers from the federal government grew at an average annual rate of 5.5 per cent, from $5.8 billion in 1990-91 to $34.3 billion in 2023-24, in nominal (not adjusted for inflation) dollars.

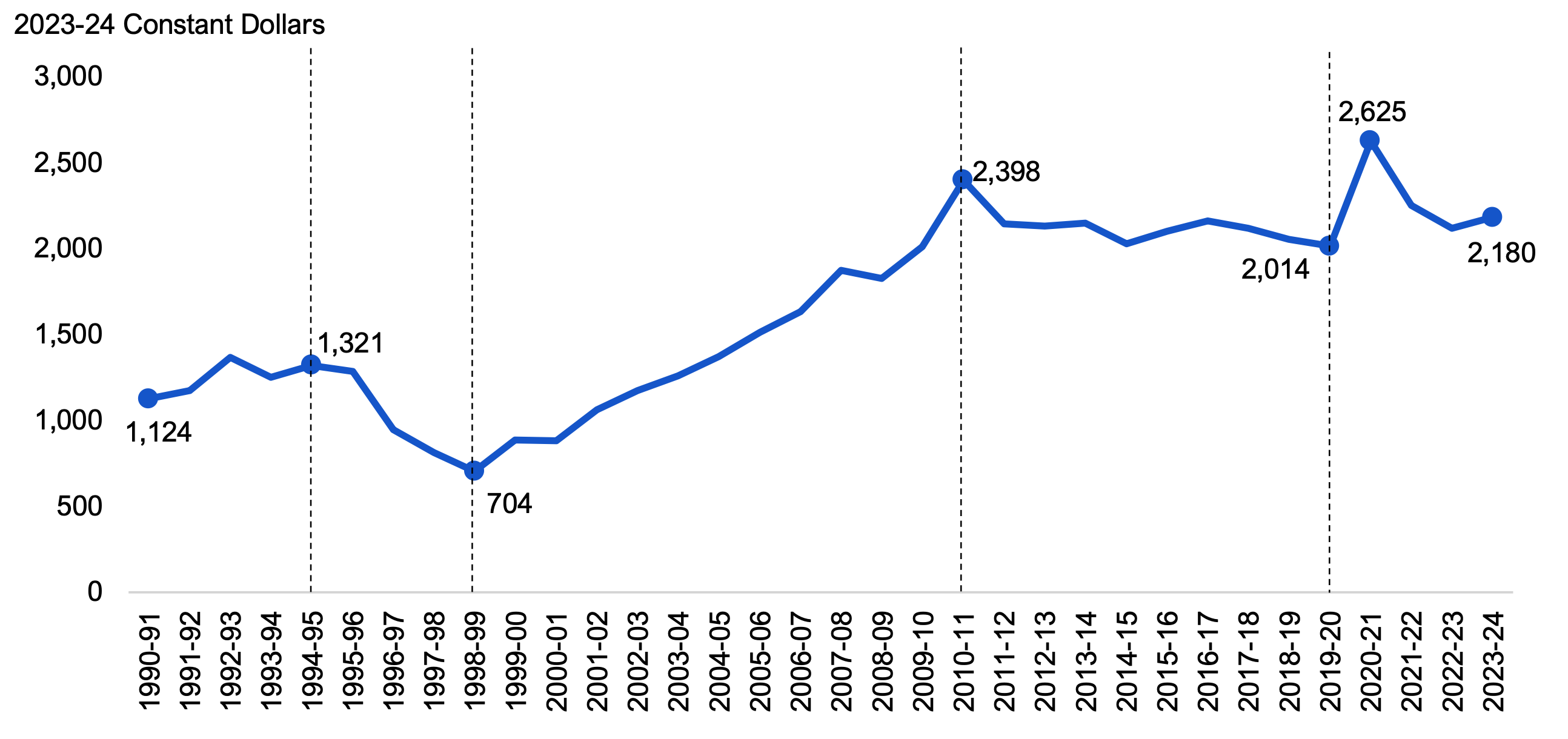

- In real per capita terms, federal transfers increased at an average annual rate of 2.0 per cent, from $1,124 per person in 1990-91 to $2,180 per person in 2023-24.

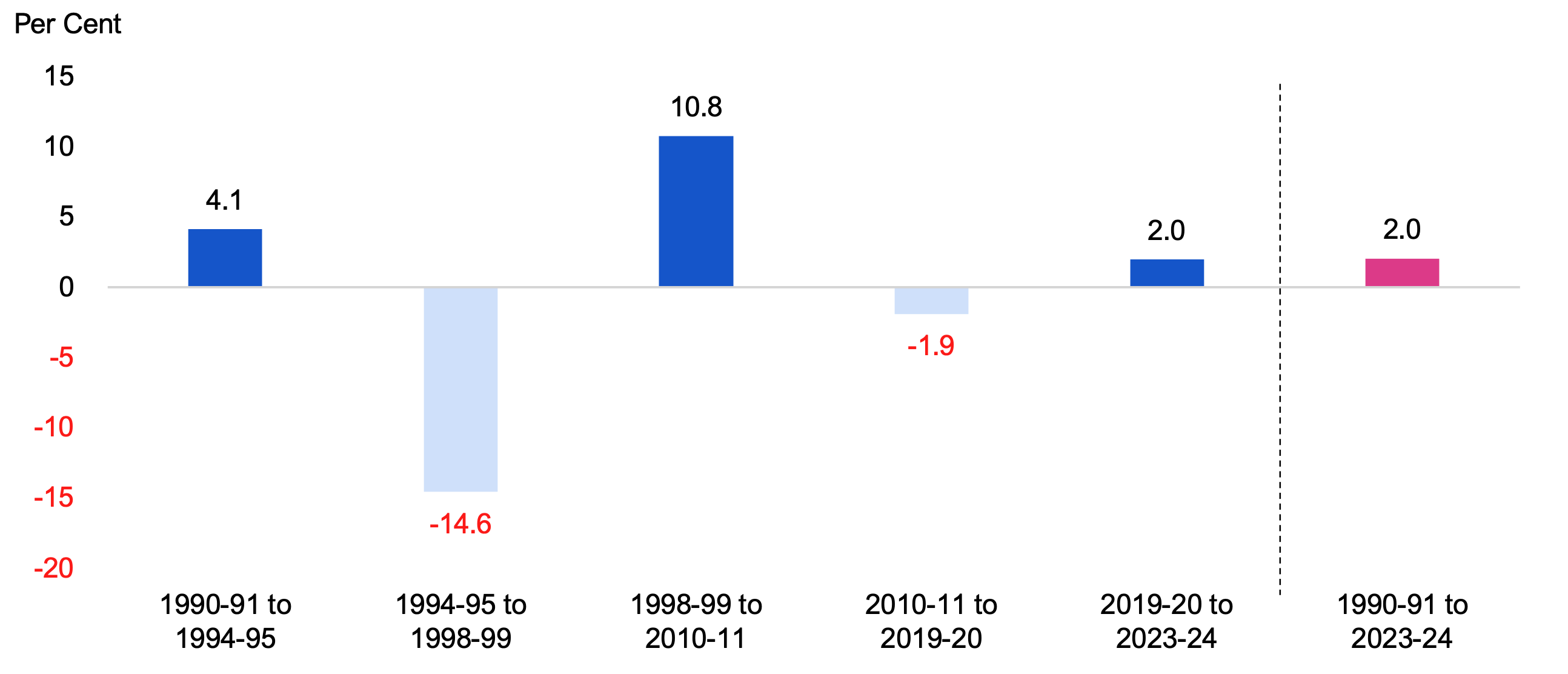

- Over the 34-year period, the FAO identified three periods of growth in real per capita federal transfers: four years from 1990-91 to 1994-95 (4.1 per cent average annual growth); 12 years from 1998-99 to 2010-11 (10.8 per cent average annual growth); and four years from 2019-20 to 2023-24 (2.0 per cent average annual growth).

- The FAO also identified two periods of declines in real per capita federal transfers: four years from 1994-95 to 1998-99 (-14.6 per cent average annual decline); and nine years from 2010-11 to 2019-20 (-1.9 per cent average annual decline).

- Comparing total federal transfers to total provincial spending provides insight on the portion of provincial spending that was supported by federal transfers compared to the Province’s own-source revenue.

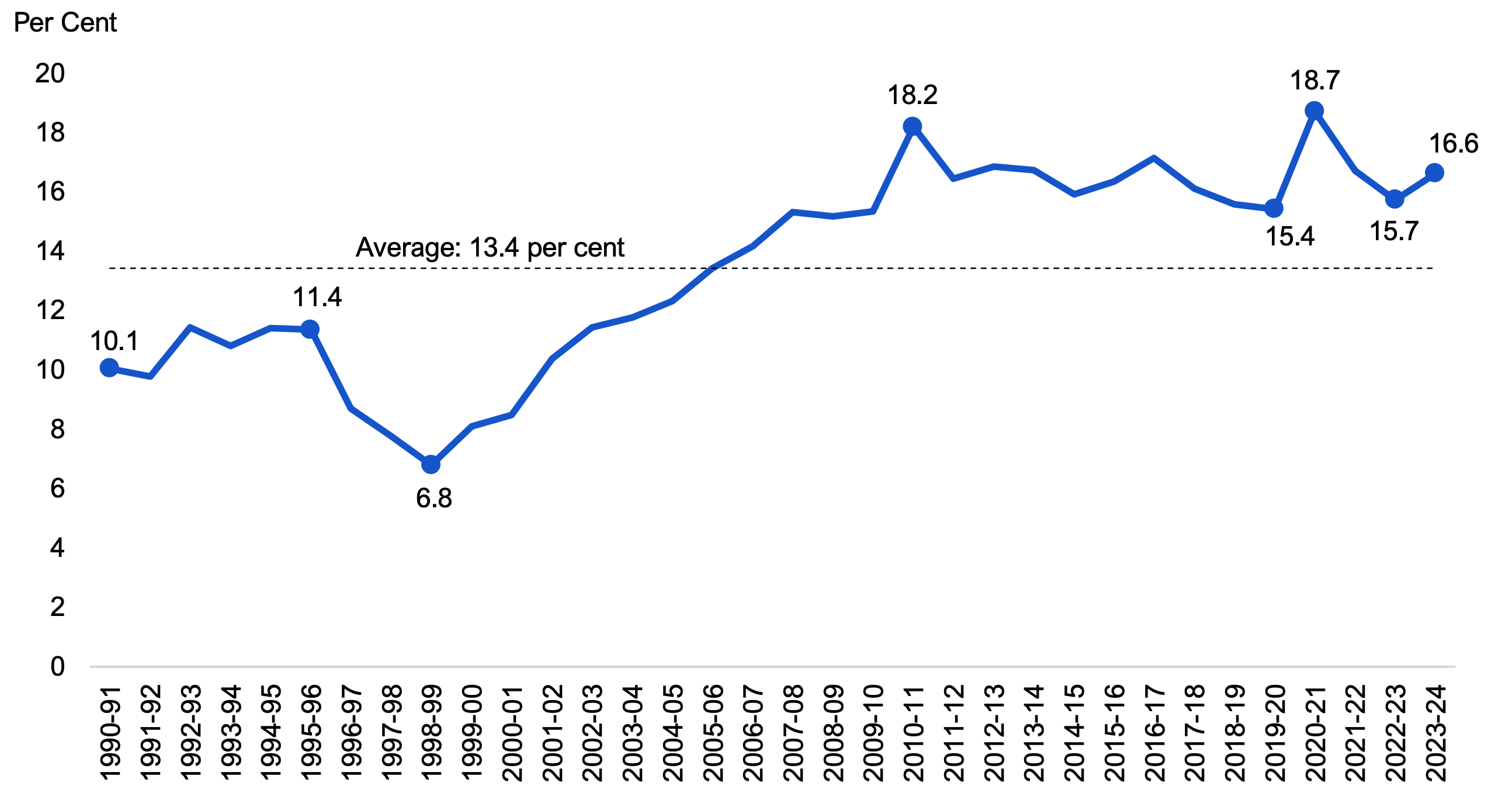

- Total federal transfers as a share of provincial spending averaged 13.4 per cent over the 34-year period and was 16.6 per cent in 2023-24.

- In each year from 1990-91 to 2004-05, federal transfers as a share of provincial spending was less than the 13.4 per cent average, with a low of 6.8 per cent in 1998-99 during a period of federal fiscal restraint.

- In each year after 2004-05, federal transfers as a share of provincial spending was higher than the 13.4 per cent average, with a high of 18.7 per cent in 2020-21 due to federal government support in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Introduction

At the request of a Member of Provincial Parliament, this report reviews Government of Ontario (the Province) spending trends from 1990-91 to 2023-24. The report also reviews trends in federal government transfers to Ontario and analyzes federal transfers as a share of provincial spending. The report is organized as follows:

- Chapter 3 reviews total Ontario government spending on a nominal and real per capita basis over the 34-year period from 1990-91 to 2023-24. This chapter also compares total government spending to nominal GDP.

- Chapter 4 reviews spending trends by sector and discusses how the share of spending by sector has changed over time.

- Chapters 5 through 11 discuss spending trends by sector: health; education; postsecondary education; children, community and social services; justice; ‘other programs’; and interest on debt. For each sector, the FAO also reviews trends in select service levels.

- Chapter 12 reviews trends in federal government transfers to Ontario and analyzes federal transfers as a share of provincial spending.

- Appendix A discusses spending trends by standard account from 2016-17 to 2023-24.

- Appendix B provides more details on sector-specific cost drivers and indicators.

- Appendix C provides information on the FAO’s adjustments to historical spending in the Public Accounts of Ontario to improve comparability over the 34-year period.

Scope

The report reviews total consolidated spending by the Province as described in the 2023-24 Public Accounts of Ontario. This includes spending by government ministries, the broader public sector organizations controlled by the Province (hospitals, school boards, colleges and Children’s Aid Societies), the Province’s agencies and the legislative offices. In addition, the report reviews trends in federal government transfers to the Province. The report does not review other provincial revenues or changes to the Province’s balance sheet.

Methodology and Sources

This report utilizes data from the Public Accounts of Ontario and various other sources, including information provided to the FAO from government entities and publicly available information from statistical agencies and other public bodies. Over the past 34 years, numerous restatements and accounting changes have occurred that have altered the presentation of Ontario’s finances. The FAO has made adjustments for these changes to improve the consistency and comparability of spending data. Detailed discussions of these adjustments can be found in Appendix C.

In this report, the FAO reviewed select service levels based on their relevance to each sector, considering factors such as the scale of program spending, the direct impact of government spending on the service level, and the availability of long-term historical data. While this report does not review all government service levels, the FAO has provided links to additional publications for further information.

Background Data

For access to the data presented in this report, please visit the FAO’s website at: https://fao-on.org/GovernmentSpendingTrendsData-EN.xlsx.

3. Ontario Government Spending Trends

Overview

In 2023-24, the Province spent a total of $206.6 billion, up from $57.6 billion in 1990-91, representing an average annual increase of 3.9 per cent. Total spending increased every year over this 34-year period, with the exception of five years: 1993-94, 1996-97, 1997-98, 2000-01 and 2012-13.

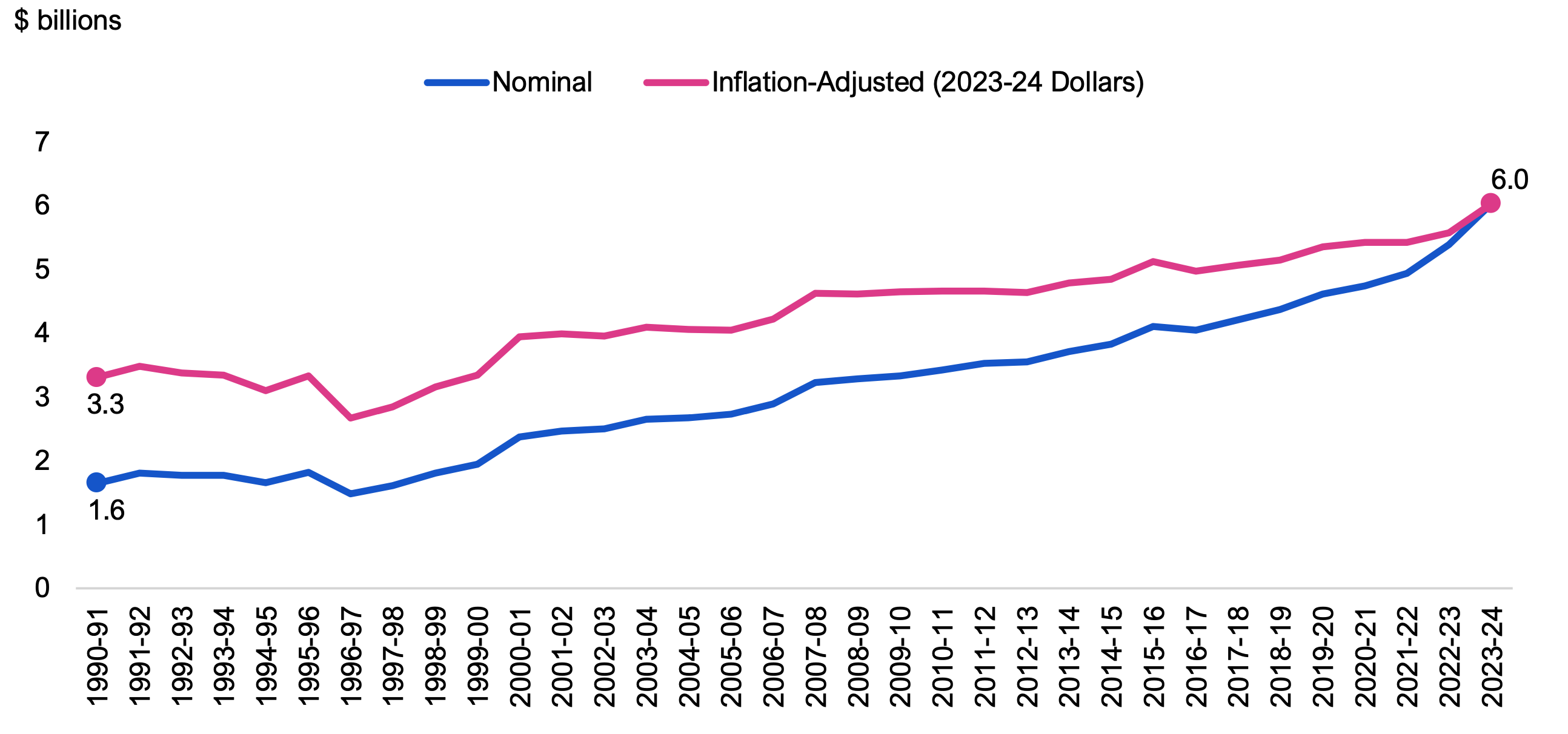

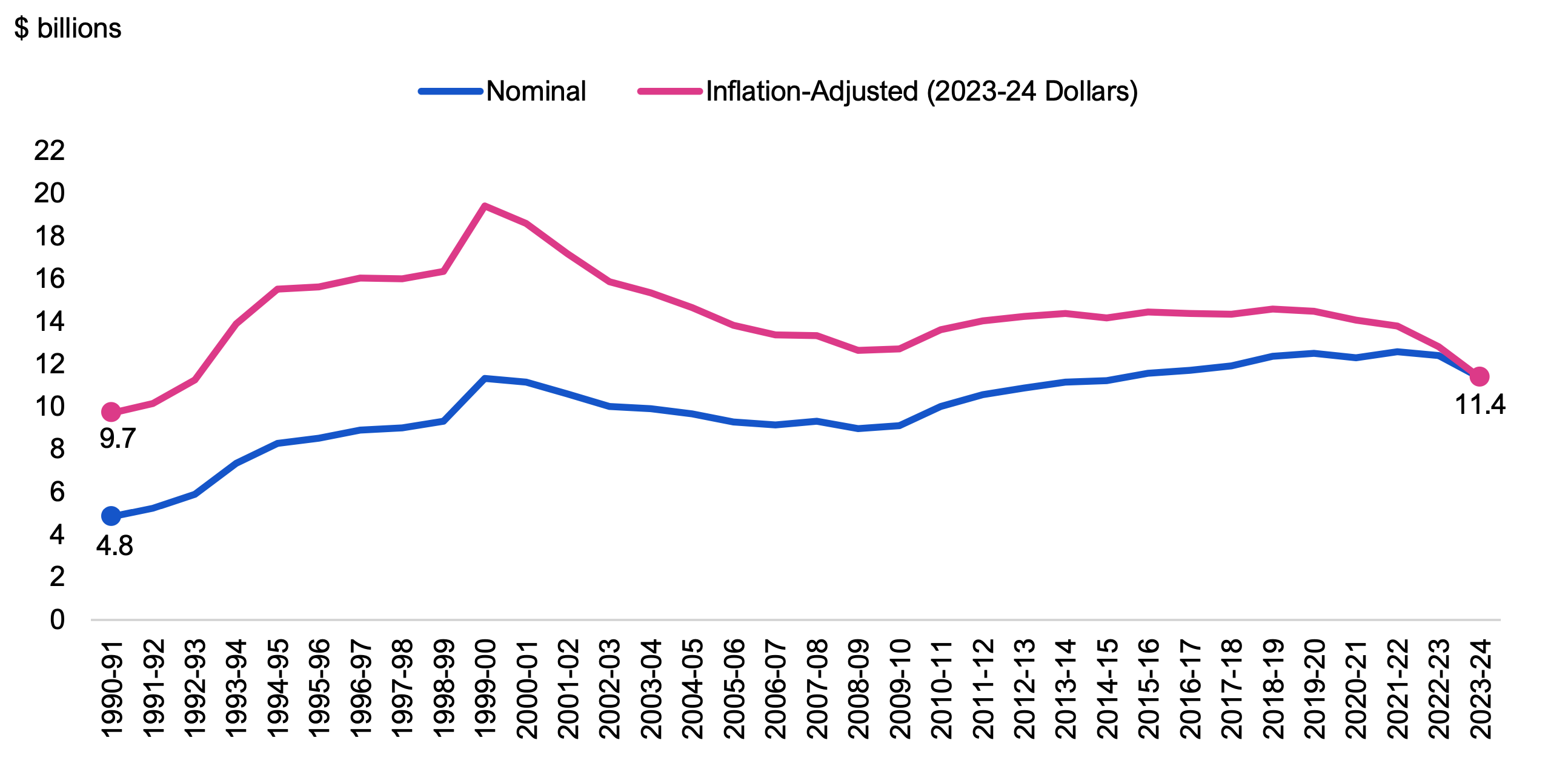

Figure 3.1 Total Ontario government spending, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: Public Accounts of Ontario, Statistics Canada and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Total Spending |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 57.6 |

| 1991-92 | 65.0 |

| 1992-93 | 66.4 |

| 1993-94 | 65.8 |

| 1994-95 | 67.0 |

| 1995-96 | 67.7 |

| 1996-97 | 67.0 |

| 1997-98 | 66.5 |

| 1998-99 | 67.3 |

| 1999-00 | 73.6 |

| 2000-01 | 73.2 |

| 2001-02 | 75.5 |

| 2002-03 | 78.6 |

| 2003-04 | 84.8 |

| 2004-05 | 90.9 |

| 2005-06 | 95.2 |

| 2006-07 | 100.0 |

| 2007-08 | 109.2 |

| 2008-09 | 110.3 |

| 2009-10 | 122.5 |

| 2010-11 | 127.7 |

| 2011-12 | 130.8 |

| 2012-13 | 129.8 |

| 2013-14 | 134.5 |

| 2014-15 | 137.4 |

| 2015-16 | 141.5 |

| 2016-17 | 143.2 |

| 2017-18 | 154.4 |

| 2018-19 | 161.1 |

| 2019-20 | 164.8 |

| 2020-21 | 181.3 |

| 2021-22 | 183.1 |

| 2022-23 | 198.7 |

| 2023-24 | 206.6 |

As a comparison, inflation and population growth, which are two broad cost drivers for government spending, have increased at a combined average annual rate of 3.4 per cent over this 34-year period, which is lower than the 3.9 per cent average annual growth in spending. Specifically, general price inflation, which increases the cost of providing public goods and services, and puts pressure on public sector wages, averaged 2.1 per cent over this period. Population growth, which drives up the demand for public services, increased at an average annual rate of 1.3 per cent from 1990-91 to 2023-24.

Looking at the 34-year period in more detail, between 1990-91 and 2005-06, government spending increased at an average annual rate of 3.4 per cent, in line with the 3.4 per cent average annual growth in population and inflation over the same period. However, from 2005-06 to 2023-24, growth in nominal spending averaged 4.4 per cent, outpacing the 3.5 per cent average annual growth in inflation and population.

Figure 3.2 Inflation and population index, and nominal spending index, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Inflation and Population Index | Nominal Spending Index |

|---|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 100 | 100 |

| 1991-92 | 105 | 113 |

| 1992-93 | 108 | 115 |

| 1993-94 | 110 | 114 |

| 1994-95 | 112 | 116 |

| 1995-96 | 116 | 118 |

| 1996-97 | 120 | 116 |

| 1997-98 | 123 | 115 |

| 1998-99 | 126 | 117 |

| 1999-00 | 131 | 128 |

| 2000-01 | 137 | 127 |

| 2001-02 | 143 | 131 |

| 2002-03 | 148 | 136 |

| 2003-04 | 154 | 147 |

| 2004-05 | 159 | 158 |

| 2005-06 | 164 | 165 |

| 2006-07 | 169 | 174 |

| 2007-08 | 173 | 190 |

| 2008-09 | 178 | 191 |

| 2009-10 | 181 | 213 |

| 2010-11 | 188 | 222 |

| 2011-12 | 195 | 227 |

| 2012-13 | 199 | 225 |

| 2013-14 | 204 | 233 |

| 2014-15 | 209 | 238 |

| 2015-16 | 214 | 246 |

| 2016-17 | 221 | 248 |

| 2017-18 | 228 | 268 |

| 2018-19 | 237 | 280 |

| 2019-20 | 245 | 286 |

| 2020-21 | 251 | 315 |

| 2021-22 | 264 | 318 |

| 2022-23 | 286 | 345 |

| 2023-24 | 306 | 359 |

Real Per Capita Spending

Nominal government spending, which does not account for changes in Ontario’s population and inflation, can obscure the true impact of government spending on service levels, especially when comparing different time periods. Therefore, analyzing spending on inflation-adjusted (i.e., real) and per capita terms offers a clearer comparison of spending levels over time. Overall, the Province’s real per capita spending has increased at an average annual rate of 0.5 per cent from $11,185 in 1990-91 to $13,118 in 2023-24.

Figure 3.3 Real per capita government spending, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Real Per Capita Spending |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 11,185 |

| 1991-92 | 11,996 |

| 1992-93 | 11,970 |

| 1993-94 | 11,564 |

| 1994-95 | 11,570 |

| 1995-96 | 11,294 |

| 1996-97 | 10,856 |

| 1997-98 | 10,467 |

| 1998-99 | 10,357 |

| 1999-00 | 10,926 |

| 2000-01 | 10,386 |

| 2001-02 | 10,243 |

| 2002-03 | 10,276 |

| 2003-04 | 10,690 |

| 2004-05 | 11,109 |

| 2005-06 | 11,268 |

| 2006-07 | 11,515 |

| 2007-08 | 12,229 |

| 2008-09 | 12,025 |

| 2009-10 | 13,114 |

| 2010-11 | 13,185 |

| 2011-12 | 13,027 |

| 2012-13 | 12,647 |

| 2013-14 | 12,818 |

| 2014-15 | 12,737 |

| 2015-16 | 12,836 |

| 2016-17 | 12,600 |

| 2017-18 | 13,137 |

| 2018-19 | 13,182 |

| 2019-20 | 13,063 |

| 2020-21 | 14,023 |

| 2021-22 | 13,457 |

| 2022-23 | 13,470 |

| 2023-24 | 13,118 |

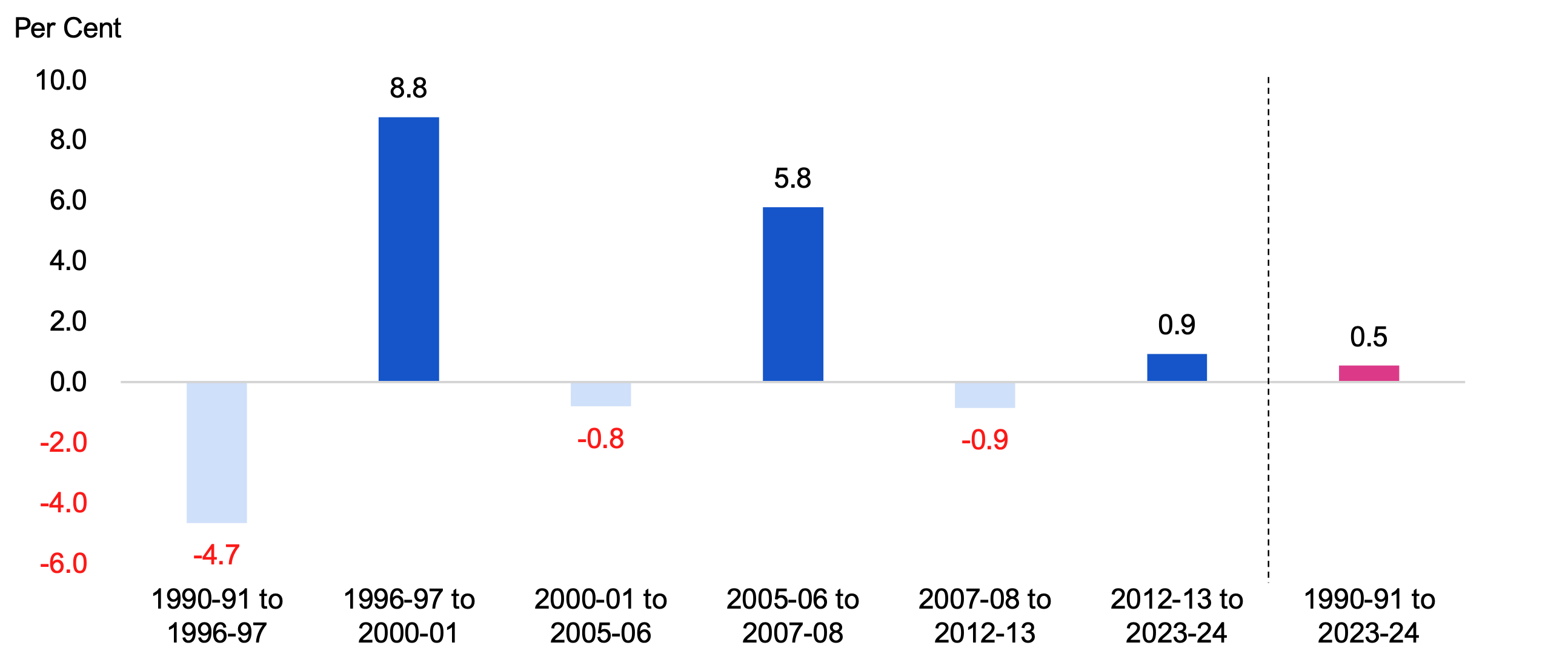

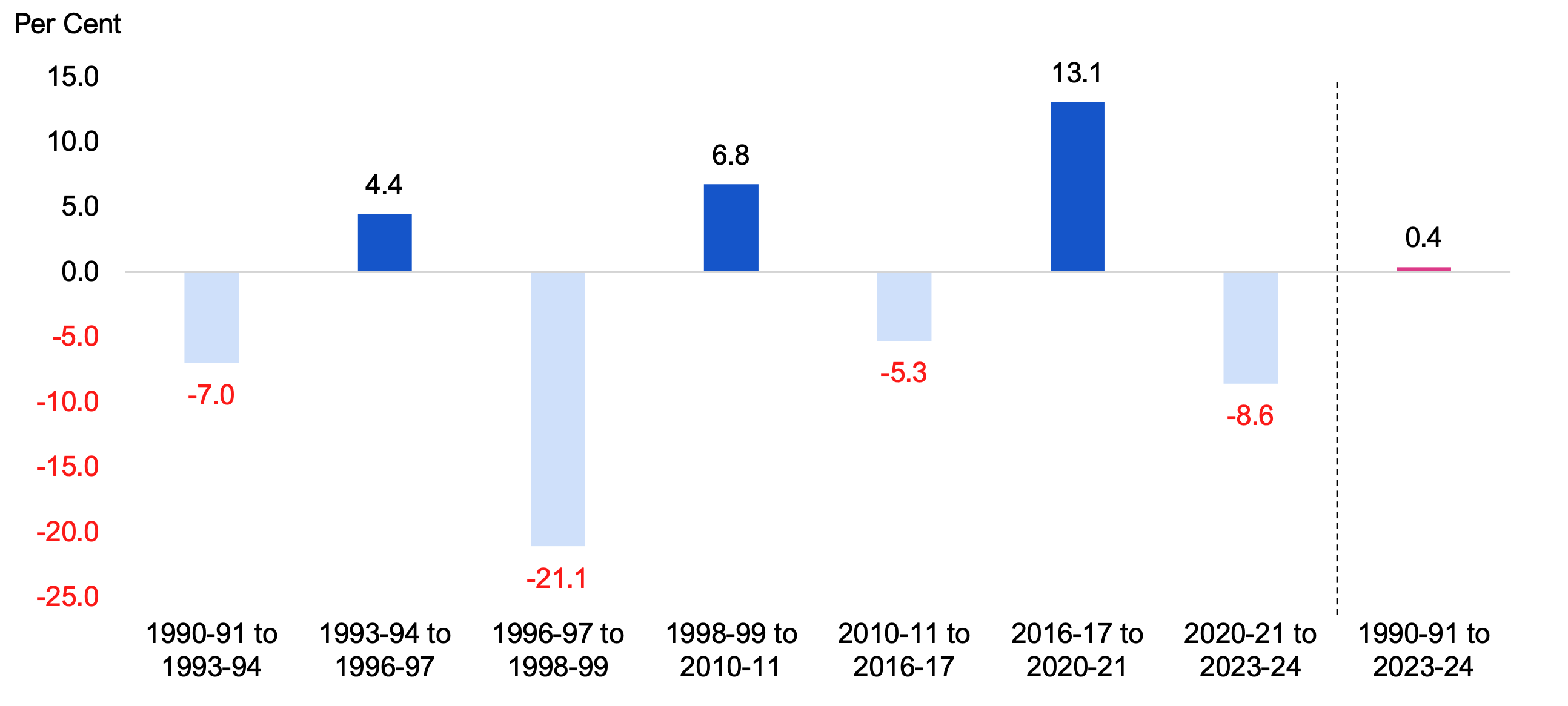

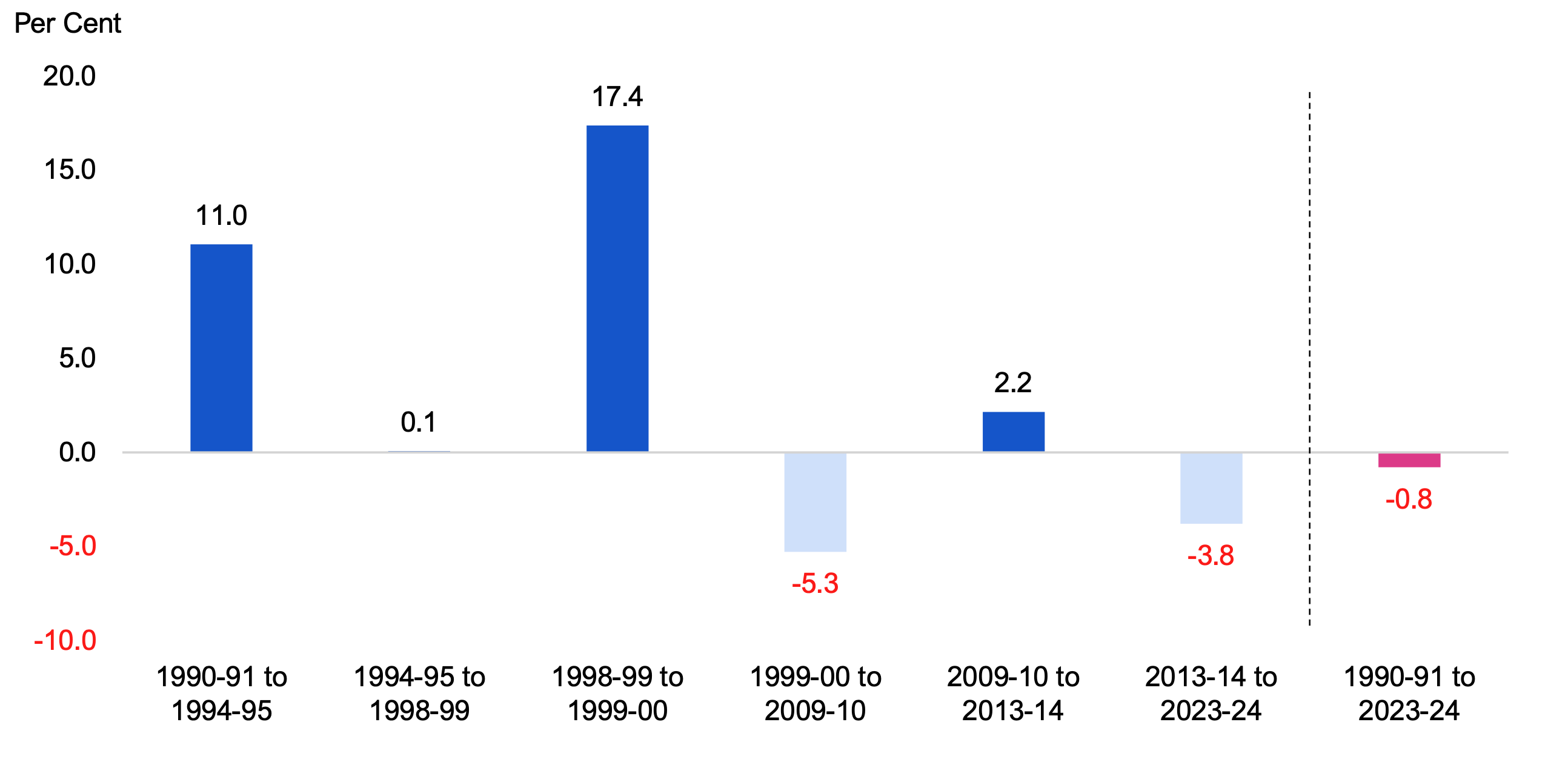

Based on real per capita spending, the FAO has identified six distinct periods of total government spending trends between 1990-91 to 2023-24:

- The first period was for one year, from 1990-91 to 1991-92, during which real per capita spending increased by 7.2 per cent, largely due to government stimulus in response to the early 1990s recession.

- The second period was for 11 years, from 1991-92 to 2002-03. Over this period, real per capita spending declined at an average annual rate of -1.4 per cent, largely due to government measures to reduce budget deficits following the early 1990s recession.

- The third period was for eight years, from 2002-03 to 2010-11. Over this period, real per capita spending increased at an average annual rate of 3.2 per cent, largely due to new and expanded programs, economic stimulus measures in response to the 2008-2009 global financial crisis and above-inflation growth in public sector wages.

- The fourth period was for six years, from 2010-11 to 2016-17. Over this period, real per capita spending declined at an average annual rate of -0.8 per cent as government spending was restrained to reduce budget deficits following the 2008-2009 global financial crisis.

- The fifth period was for four years, from 2016-17 to 2020-21. Over this period, real per capita spending increased at an average annual rate of 2.7 per cent, largely due to new and expanded programs and spending in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The sixth period was for three years, from 2020-21 to 2023-24. Over this period, real per capita spending declined at an average annual rate of -2.2 per cent, primarily due to high inflation and population growth combined with the expiry of time limited spending in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 3.4 Average annual real per capita spending growth in Ontario by period, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Years | 1990-91 to 1991-92 | 1991-92 to 2002-03 | 2002-03 to 2010-11 | 2010-11 to 2016-17 | 2016-17 to 2020-21 | 2020-21 to 2023-24 | 1990-91 to 2023-24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Annual Growth | 7.2 | -1.4 | 3.2 | -0.8 | 2.7 | -2.2 | 0.5 |

Spending as a Share of the Economy

Another approach to analyzing government spending trends is to compare nominal government spending to nominal gross domestic product (GDP). As nominal GDP is the broadest measure of the tax base, this comparison provides insight into the size of government spending relative to the economy’s ability to pay. Spending as a share of Ontario’s GDP averaged 18.6 per cent over the 34-year period.

Figure 3.5 Government spending as a share of nominal GDP, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Spending as a Share of Nominal GDP | Average |

|---|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 20.0 | 18.6 |

| 1991-92 | 22.4 | 18.6 |

| 1992-93 | 22.5 | 18.6 |

| 1993-94 | 21.4 | 18.6 |

| 1994-95 | 20.6 | 18.6 |

| 1995-96 | 19.9 | 18.6 |

| 1996-97 | 18.9 | 18.6 |

| 1997-98 | 17.7 | 18.6 |

| 1998-99 | 17.0 | 18.6 |

| 1999-00 | 17.2 | 18.6 |

| 2000-01 | 16.0 | 18.6 |

| 2001-02 | 15.9 | 18.6 |

| 2002-03 | 15.7 | 18.6 |

| 2003-04 | 16.4 | 18.6 |

| 2004-05 | 16.8 | 18.6 |

| 2005-06 | 16.9 | 18.6 |

| 2006-07 | 17.1 | 18.6 |

| 2007-08 | 18.1 | 18.6 |

| 2008-09 | 18.2 | 18.6 |

| 2009-10 | 20.2 | 18.6 |

| 2010-11 | 20.0 | 18.6 |

| 2011-12 | 19.6 | 18.6 |

| 2012-13 | 19.0 | 18.6 |

| 2013-14 | 19.1 | 18.6 |

| 2014-15 | 18.7 | 18.6 |

| 2015-16 | 18.4 | 18.6 |

| 2016-17 | 17.9 | 18.6 |

| 2017-18 | 18.5 | 18.6 |

| 2018-19 | 18.6 | 18.6 |

| 2019-20 | 18.5 | 18.6 |

| 2020-21 | 20.2 | 18.6 |

| 2021-22 | 18.4 | 18.6 |

| 2022-23 | 18.5 | 18.6 |

| 2023-24 | 18.2 | 18.6 |

During the early 1990s recession, spending as a share of GDP increased to a peak of 22.5 per cent in 1992-93 due to higher nominal government spending and relatively low GDP growth. Over the following years, the share decreased to a low of 15.7 per cent in 2002-03, reflecting a period of spending restraint combined with a pickup in economic growth. The share increased to 20.2 per cent in 2009-10, driven by slow GDP growth and increased government spending and economic stimulus measures in response to the 2008-2009 global financial crisis. From 2009-10 to 2016-17, government spending as a share of GDP declined from 20.2 per cent to 17.9 per cent, reflecting government spending restraint in the early 2010s to reduce budget deficits following the financial crisis. Since 2016-17, spending as a share of GDP has grown moderately to 18.2 per cent in 2023-24, with the exception of a sharp increase to 20.2 per cent in 2020-21 due to increased spending and slow GDP growth during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Spending Trends by Sector

The Province categorizes its spending into seven sectors: health; education; postsecondary education; children, community and social services; justice; ‘other programs’; and interest on debt. As outlined in Chapter 3, from 1990-91 to 2023-24, total nominal government spending grew at an average annual rate of 3.9 per cent. This growth has varied by the seven sectors. Overall, three sectors, health (5.0 per cent), postsecondary education (4.2 per cent) and justice (4.0 per cent) experienced above average annual growth over the 34-year period, while four sectors, ‘other programs’ (3.8 per cent), children, community and social services (3.1 per cent), education (3.1 per cent) and interest on debt (2.6 per cent) experienced below average annual growth.

Figure 4.1 Average annual spending growth by sector, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: Public Accounts of Ontario, Statistics Canada and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Sector | Average Annual Spending Growth |

|---|---|

| Health | 5.0 |

| Education | 3.1 |

| Postsecondary Education | 4.2 |

| Children, Community and Social Services | 3.1 |

| Justice | 4.0 |

| Other Programs | 3.8 |

| Interest on Debt | 2.6 |

| Total Spending | 3.9 |

These different spending growth rates have led to changes in each sector’s spending as a share of total spending:

- The health sector has been the largest spending sector throughout the 34-year period, while its share of total spending has steadily increased, from 29.3 per cent in 1990-91 to 41.4 per cent in 2023-24.

- The second largest spending sector over this period was education; however, education sector spending as a share of total spending has steadily declined, from 24.8 per cent in 1990-91 to 18.8 per cent in 2023-24.

- Spending on postsecondary education increased from 5.9 per cent of total spending in 1990-91 to 6.4 per cent in 2023-24.

- Children, community and social services spending decreased from 12.5 per cent of total spending in 1990-91 to 9.4 per cent in 2023-24.

- Justice sector spending as a share of total spending has remained relatively unchanged, at 2.9 per cent of total spending in both 1990-91 and 2023-24.

- ‘Other programs’ sector spending as a share of total spending has fluctuated over time, ranging between 10.0 per cent and 19.1 per cent of total spending. In 1990-91 ‘other programs’ spending was 16.2 per cent of total spending, while in 2023-24 it was 15.6 per cent of total spending.

- Interest on debt spending as a share of total spending increased from 8.4 per cent in 1990-91 to 15.4 per cent in 1999-00, and then steadily declined to 5.5 per cent of total spending in 2023-24.

Figure 4.2 Share of total spending by sector, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: Public Accounts of Ontario, Statistics Canada and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Share of Total Government Spending | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Education | Postsecondary Education | Children, Community and Social Services | Justice | Other Programs | Interest on Debt | |

| 1990-91 | 29.3% | 24.8% | 5.9% | 12.5% | 2.9% | 16.2% | 8.4% |

| 1991-92 | 29.4% | 25.4% | 6.0% | 13.4% | 2.8% | 14.9% | 8.1% |

| 1992-93 | 29.2% | 24.6% | 6.0% | 14.2% | 2.7% | 14.5% | 8.9% |

| 1993-94 | 29.1% | 24.1% | 5.2% | 15.0% | 2.7% | 12.6% | 11.2% |

| 1994-95 | 28.9% | 22.9% | 5.0% | 15.0% | 2.5% | 13.4% | 12.3% |

| 1995-96 | 28.4% | 23.1% | 5.1% | 14.4% | 2.7% | 13.7% | 12.6% |

| 1996-97 | 28.8% | 22.7% | 4.7% | 12.9% | 2.2% | 15.3% | 13.3% |

| 1997-98 | 30.1% | 22.2% | 5.4% | 13.0% | 2.4% | 13.3% | 13.6% |

| 1998-99 | 31.5% | 23.0% | 5.8% | 13.2% | 2.7% | 10.0% | 13.8% |

| 1999-00 | 32.0% | 21.4% | 5.8% | 12.0% | 2.6% | 10.8% | 15.4% |

| 2000-01 | 32.3% | 21.1% | 5.4% | 9.6% | 3.2% | 13.2% | 15.3% |

| 2001-02 | 34.5% | 21.0% | 5.2% | 9.5% | 3.3% | 12.5% | 14.0% |

| 2002-03 | 36.1% | 21.0% | 5.4% | 9.4% | 3.2% | 12.3% | 12.7% |

| 2003-04 | 37.4% | 20.8% | 5.6% | 9.1% | 3.1% | 12.3% | 11.7% |

| 2004-05 | 37.5% | 21.1% | 5.8% | 9.0% | 2.9% | 13.0% | 10.6% |

| 2005-06 | 37.1% | 20.8% | 5.8% | 9.2% | 2.9% | 14.4% | 9.8% |

| 2006-07 | 38.2% | 20.4% | 6.2% | 9.3% | 2.9% | 13.8% | 9.1% |

| 2007-08 | 37.5% | 19.5% | 6.5% | 9.1% | 3.0% | 15.9% | 8.5% |

| 2008-09 | 39.5% | 20.3% | 6.1% | 9.7% | 3.0% | 13.2% | 8.1% |

| 2009-10 | 37.7% | 19.1% | 6.2% | 9.6% | 2.7% | 17.3% | 7.4% |

| 2010-11 | 37.2% | 18.9% | 6.3% | 9.8% | 2.7% | 17.2% | 7.8% |

| 2011-12 | 38.2% | 19.3% | 6.3% | 10.0% | 2.7% | 15.4% | 8.1% |

| 2012-13 | 39.5% | 18.5% | 6.3% | 10.3% | 2.7% | 14.4% | 8.4% |

| 2013-14 | 39.3% | 19.2% | 6.5% | 10.1% | 2.8% | 13.9% | 8.3% |

| 2014-15 | 39.5% | 19.6% | 6.4% | 10.4% | 2.8% | 13.1% | 8.2% |

| 2015-16 | 39.0% | 19.5% | 6.4% | 10.7% | 2.9% | 13.4% | 8.2% |

| 2016-17 | 39.3% | 19.2% | 6.6% | 10.9% | 2.8% | 13.0% | 8.2% |

| 2017-18 | 38.3% | 18.7% | 6.8% | 10.5% | 2.7% | 15.2% | 7.7% |

| 2018-19 | 38.4% | 18.9% | 6.9% | 10.4% | 2.7% | 15.0% | 7.7% |

| 2019-20 | 38.7% | 19.3% | 6.4% | 10.3% | 2.8% | 14.9% | 7.6% |

| 2020-21 | 38.3% | 18.1% | 5.4% | 9.6% | 2.6% | 19.1% | 6.8% |

| 2021-22 | 41.4% | 17.2% | 5.8% | 9.3% | 2.7% | 16.7% | 6.9% |

| 2022-23 | 39.5% | 18.2% | 5.9% | 9.1% | 2.7% | 18.3% | 6.2% |

| 2023-24 | 41.4% | 18.8% | 6.4% | 9.4% | 2.9% | 15.6% | 5.5% |

Chapters 5 through 11 review spending trends in the seven sectors in more detail.

5. Health

Spending Trends

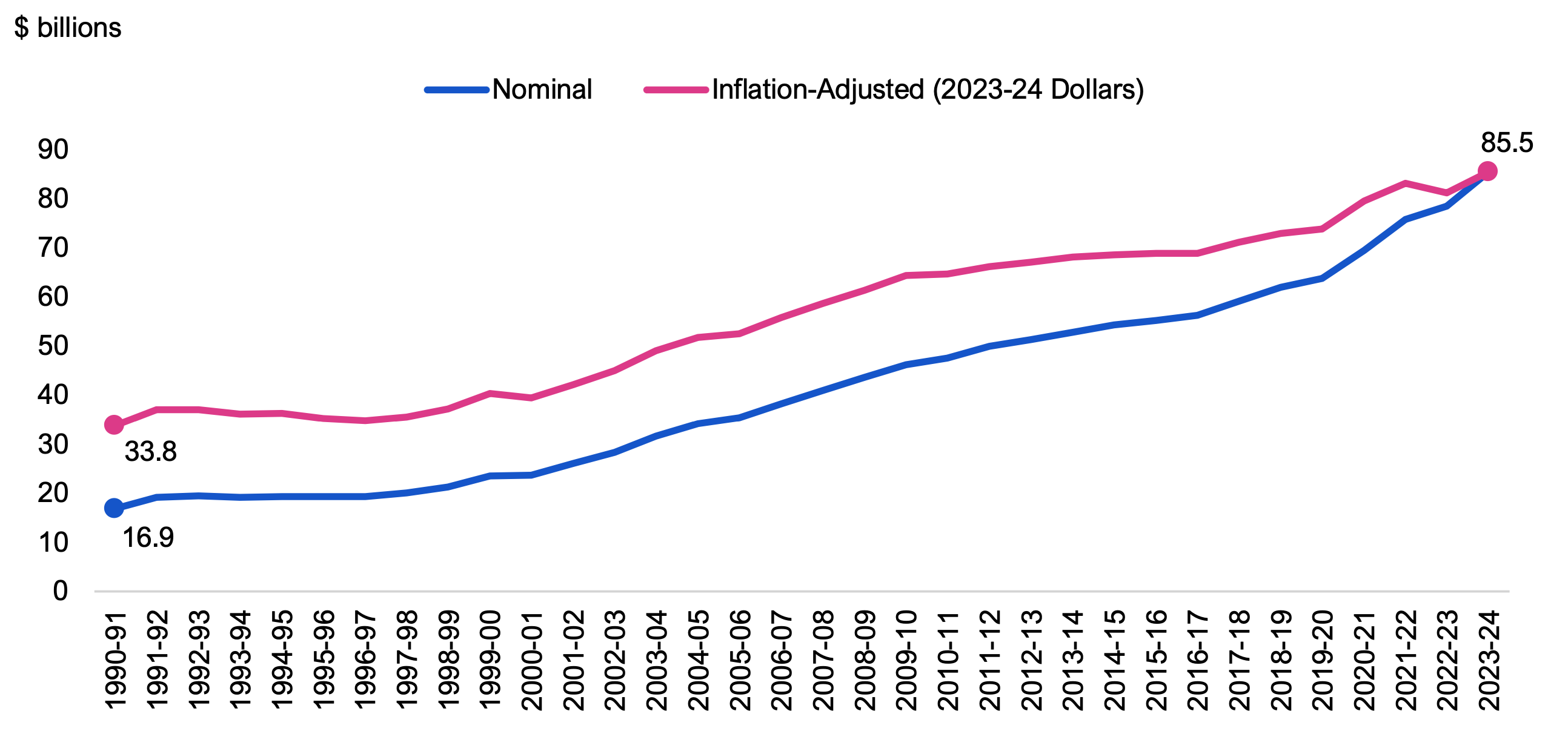

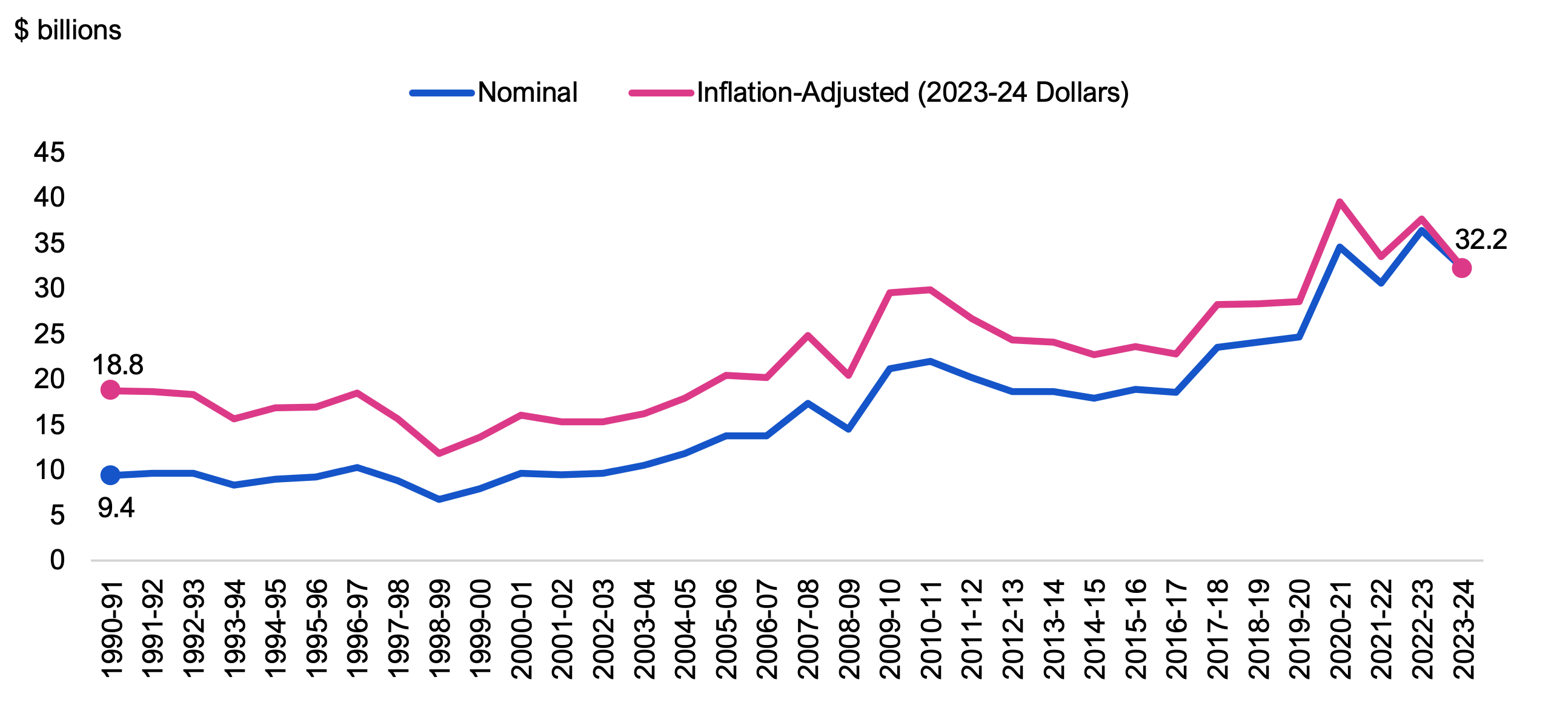

Health is the largest sector in the government, accounting for 41.4 per cent of total spending in 2023-24. The health sector consists of spending on hospitals, physician services, long-term care, community care, public drug programs and other provincially funded health services.[1] The FAO estimates that health sector spending grew at an average annual rate of 5.0 per cent from $16.9 billion in 1990-91 to $85.5 billion in 2023-24. After adjusting for inflation, this sector’s spending grew at an average annual rate of 2.9 per cent from 1990-91 to 2023-24.

Figure 5.1 Health sector spending, nominal and inflation-adjusted, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Nominal | Inflation-Adjusted (2023-24 Dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 16.9 | 33.8 |

| 1991-92 | 19.1 | 37.0 |

| 1992-93 | 19.4 | 37.0 |

| 1993-94 | 19.2 | 36.1 |

| 1994-95 | 19.3 | 36.2 |

| 1995-96 | 19.2 | 35.3 |

| 1996-97 | 19.3 | 34.8 |

| 1997-98 | 20.0 | 35.5 |

| 1998-99 | 21.2 | 37.2 |

| 1999-00 | 23.5 | 40.4 |

| 2000-01 | 23.6 | 39.4 |

| 2001-02 | 26.0 | 42.2 |

| 2002-03 | 28.3 | 44.9 |

| 2003-04 | 31.7 | 49.0 |

| 2004-05 | 34.1 | 51.8 |

| 2005-06 | 35.3 | 52.5 |

| 2006-07 | 38.2 | 55.8 |

| 2007-08 | 40.9 | 58.6 |

| 2008-09 | 43.6 | 61.4 |

| 2009-10 | 46.1 | 64.4 |

| 2010-11 | 47.5 | 64.6 |

| 2011-12 | 50.0 | 66.2 |

| 2012-13 | 51.2 | 67.0 |

| 2013-14 | 52.8 | 68.2 |

| 2014-15 | 54.3 | 68.6 |

| 2015-16 | 55.2 | 68.8 |

| 2016-17 | 56.2 | 68.9 |

| 2017-18 | 59.1 | 71.2 |

| 2018-19 | 61.9 | 72.9 |

| 2019-20 | 63.7 | 73.9 |

| 2020-21 | 69.5 | 79.5 |

| 2021-22 | 75.8 | 83.0 |

| 2022-23 | 78.5 | 81.2 |

| 2023-24 | 85.5 | 85.5 |

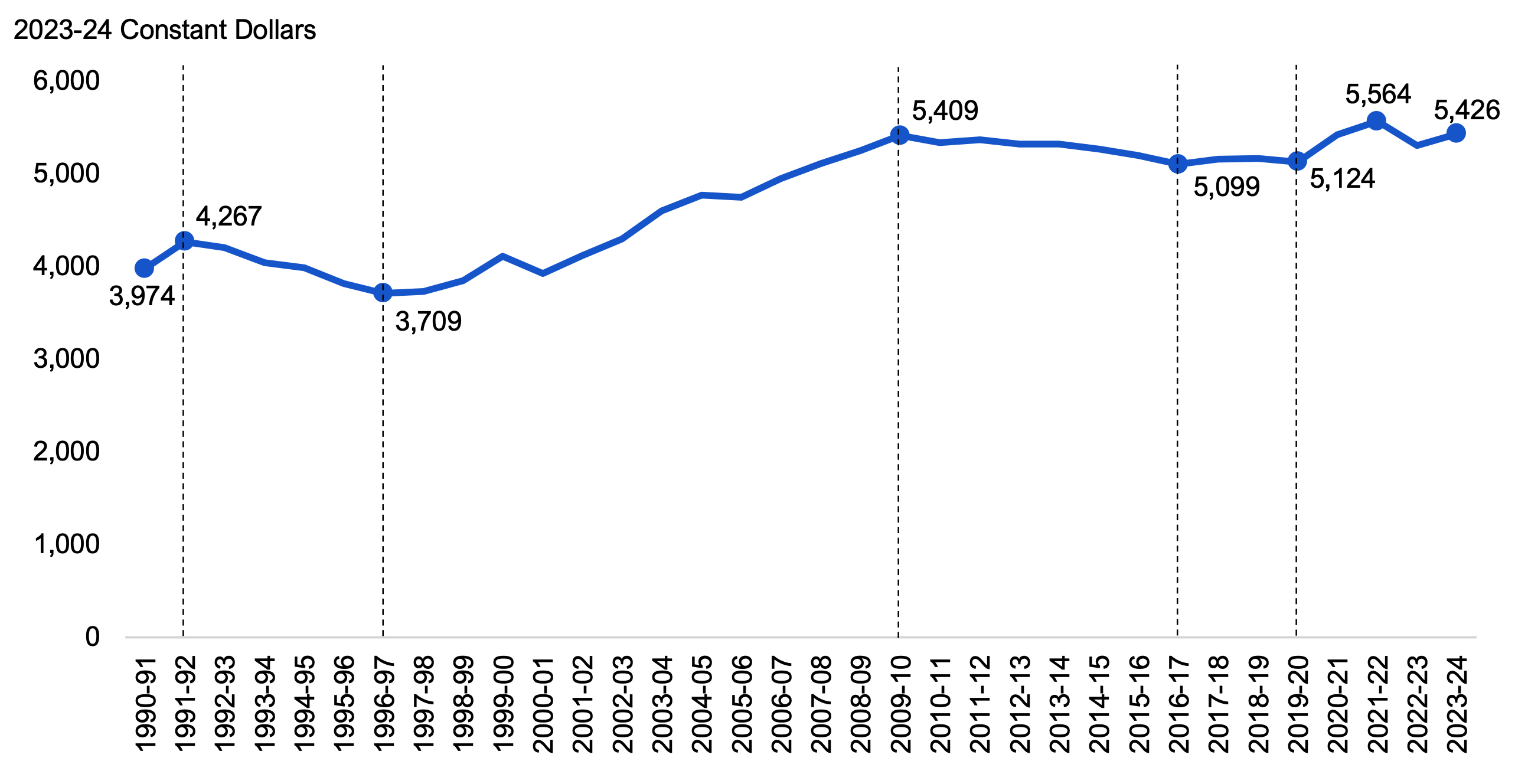

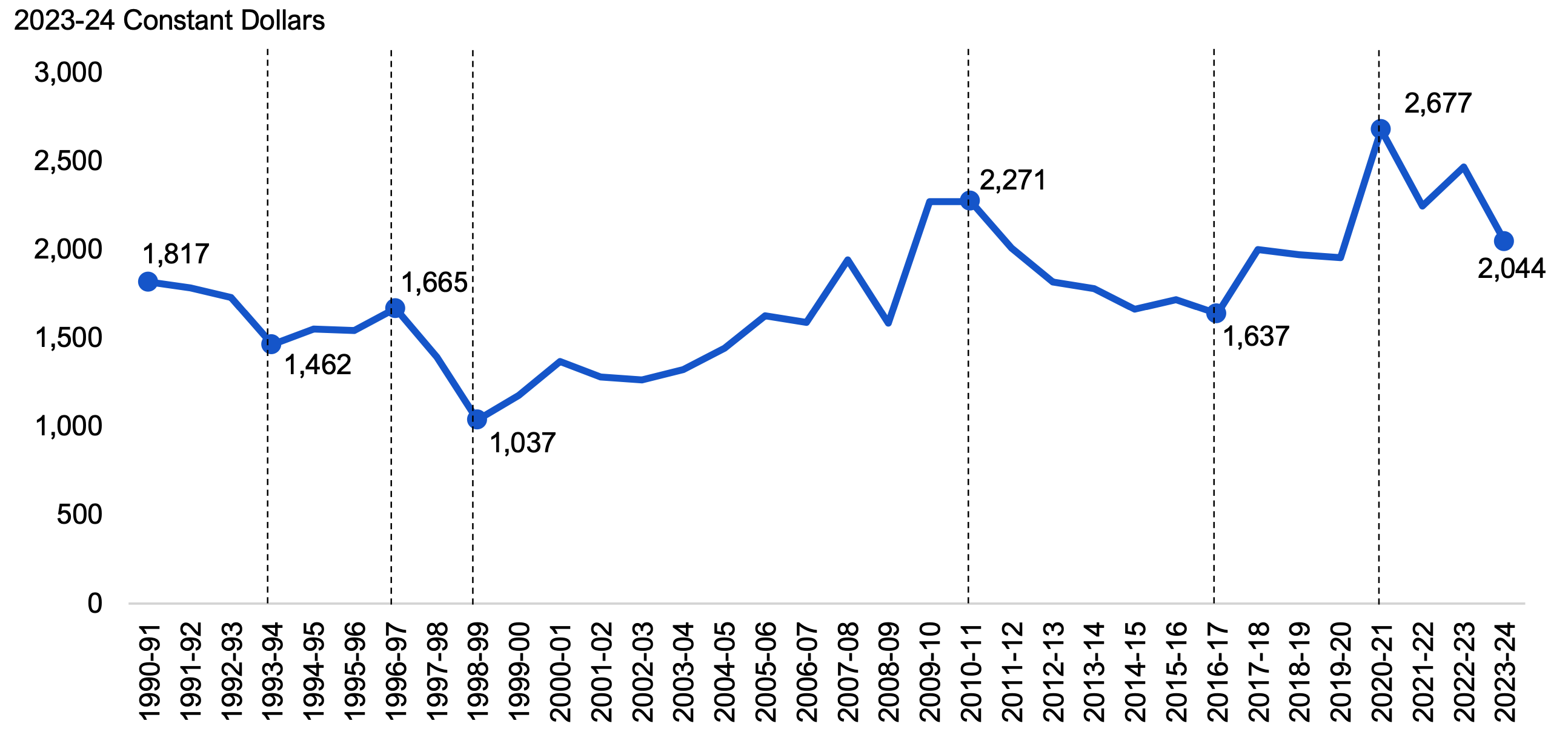

In addition to inflation, population growth and aging are core cost drivers for health sector spending.[2] The following presents health sector spending on a real per capita basis, adjusted for the age structure of Ontario’s population. This allows for a better comparison of the impact that health sector spending has on service levels over time after considering the effect of inflation on prices and the effect of population growth and aging on demand for health care services. Overall, age-standardized real per capita spending increased at an average annual rate of 0.9 per cent from $3,974 per person in 1990-91 to $5,426 per person in 2023-24.

Figure 5.2 Age-standardized real per capita health sector spending, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO analysis of CIHI National Health Expenditure Trends, 2024: Data Tables — Series E1, the Public Accounts of Ontario, Statistics Canada, and information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Age-Standardized Real Per Capita Health Sector Spending |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 3,974 |

| 1991-92 | 4,267 |

| 1992-93 | 4,205 |

| 1993-94 | 4,037 |

| 1994-95 | 3,987 |

| 1995-96 | 3,815 |

| 1996-97 | 3,709 |

| 1997-98 | 3,731 |

| 1998-99 | 3,848 |

| 1999-00 | 4,106 |

| 2000-01 | 3,925 |

| 2001-02 | 4,117 |

| 2002-03 | 4,298 |

| 2003-04 | 4,601 |

| 2004-05 | 4,766 |

| 2005-06 | 4,744 |

| 2006-07 | 4,948 |

| 2007-08 | 5,105 |

| 2008-09 | 5,249 |

| 2009-10 | 5,409 |

| 2010-11 | 5,330 |

| 2011-12 | 5,361 |

| 2012-13 | 5,320 |

| 2013-14 | 5,318 |

| 2014-15 | 5,266 |

| 2015-16 | 5,195 |

| 2016-17 | 5,099 |

| 2017-18 | 5,156 |

| 2018-19 | 5,164 |

| 2019-20 | 5,124 |

| 2020-21 | 5,415 |

| 2021-22 | 5,564 |

| 2022-23 | 5,306 |

| 2023-24 | 5,426 |

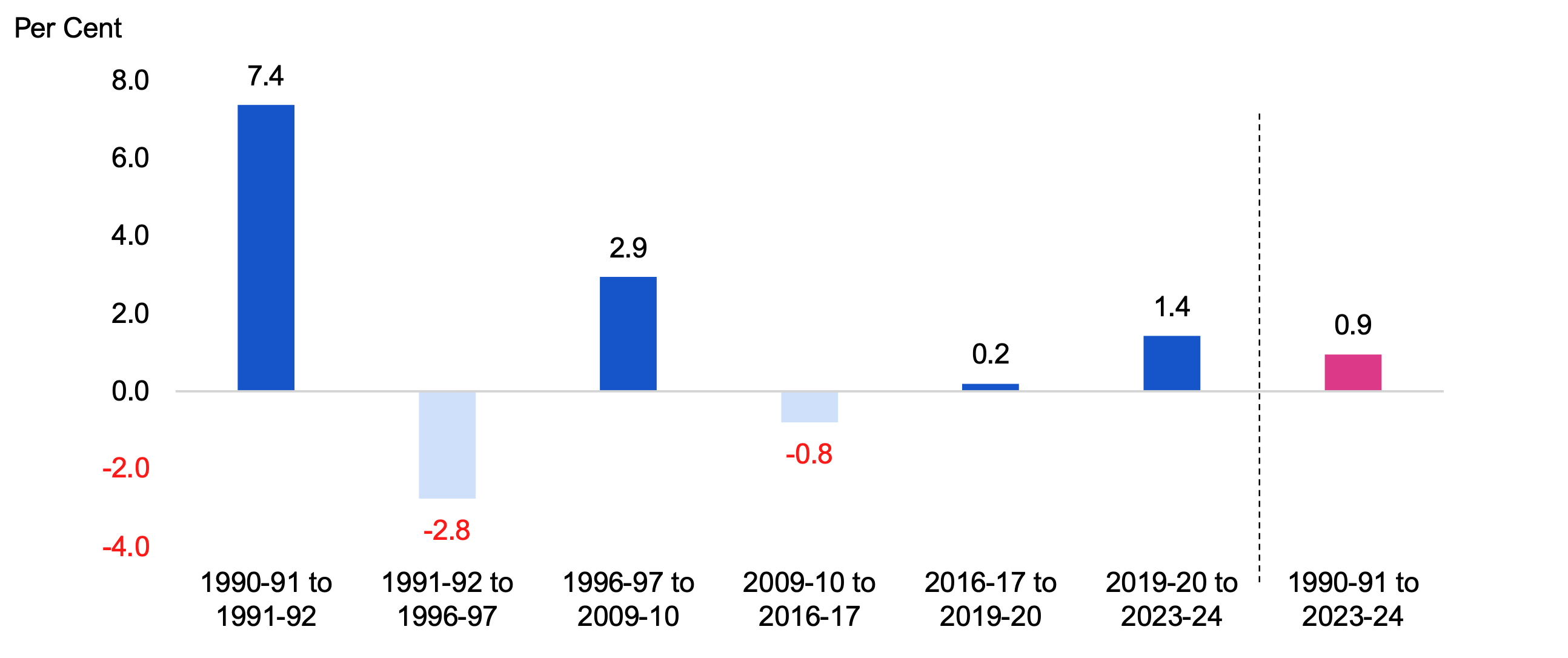

Based on age-standardized real per capita spending, the FAO has identified six distinct periods of health sector spending between 1990-91 to 2023-24:

1990-91 to 1991-92

From 1990-91 to 1991-92, age-standardized real per capita spending increased by 7.4 per cent from $3,974 to $4,267. This growth was driven by increased spending for hospitals, physician services and drug programs.

1991-92 to 1996-97

From 1991-92 to 1996-97, age-standardized real per capita spending declined from $4,267 to $3,709 at an average annual rate of -2.8 per cent. This period was characterized by significant health sector spending restraint driven by relatively flat spending for hospitals due to reductions in hospital capacity. Additionally, there was a nominal decline in spending for physician services resulting from reductions in physician fees and a hard cap on physician billing that was in place from 1993 to 1996.[3]

1996-97 to 2009-10

From 1996-97 to 2009-10, age-standardized real per capita health spending grew from $3,709 to $5,409 at an average annual rate of 2.9 per cent. Significant contributors to this growth include increases in spending on physician services following reforms to physician compensation, expansion of the long-term care sector, and growth in drug program spending.

2009-10 to 2016-17

From 2009-10 to 2016-17, age-standardized real per capita health spending declined from $5,409 to $5,099 at an average annual rate of -0.8 per cent. During this period, the government introduced health spending restraint measures, which included freezing hospital global budgets from 2012-13 to 2015-16, and reducing physician fees in 2013 and 2015. Additionally, drug program spending growth slowed following the establishment of the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance in 2010.[4] These measures were partially offset by increased spending on home care.

2016-17 to 2019-20

From 2016-17 to 2019-20, age-standardized real per capita health spending increased from $5,099 to $5,124 at an average annual rate of 0.2 per cent. This period was characterized by increased nominal health spending that was largely offset by inflation, population growth and population aging. Higher nominal health spending was led by increased spending for physician services following a 2019 arbitration decision that increased physician fees and the 2013 and 2015 fee reductions;[5] for drug programs, including the introduction of OHIP+ which provides prescription drug coverage to eligible Ontarians aged 24 and under; and for mental health services, supported by the Canada-Ontario Home and Community Care and Mental Health and Addictions Services Funding Agreement.

2019-20 to 2023-24

From 2019-20 to 2023-24, age-standardized real per capita health spending grew from $5,124 to a peak of $5,564 in 2021-22 before falling to $5,426 in 2023-24, for an average annual growth rate of 1.4 per cent. This period was characterized by time-limited health sector spending in response to the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020-21 to 2022-23, as well as investments to increase capacity in hospitals, home care and long-term care. Additionally, in 2022-23 and 2023-24, the Province recorded expenses for retroactive compensation related to Bill 124, the Protecting a Sustainable Public Sector for Future Generations Act, 2019.

Figure 5.3 Average annual growth in age-standardized real per capita health sector spending, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO analysis of CIHI National Health Expenditure Trends, 2022: Data Tables — Series E1, the Public Accounts of Ontario, Statistics Canada, and information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Years | 1990-91 to 1991-92 | 1991-92 to 1996-97 | 1996-97 to 2009-10 | 2009-10 to 2016-17 | 2016-17 to 2019-20 | 2019-20 to 2023-24 | 1990-91 to 2023-24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Annual Growth | 7.4 | -2.8 | 2.9 | -0.8 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

Select Service Levels

In this section, the FAO analyzes three broad service level trends: number of hospital beds, number of physicians and number of long-term care beds. There are many other measures of health system service levels and performance. For more information, see Ontario Health, Health System Performance Reporting and CIHI, health system performance measurement.

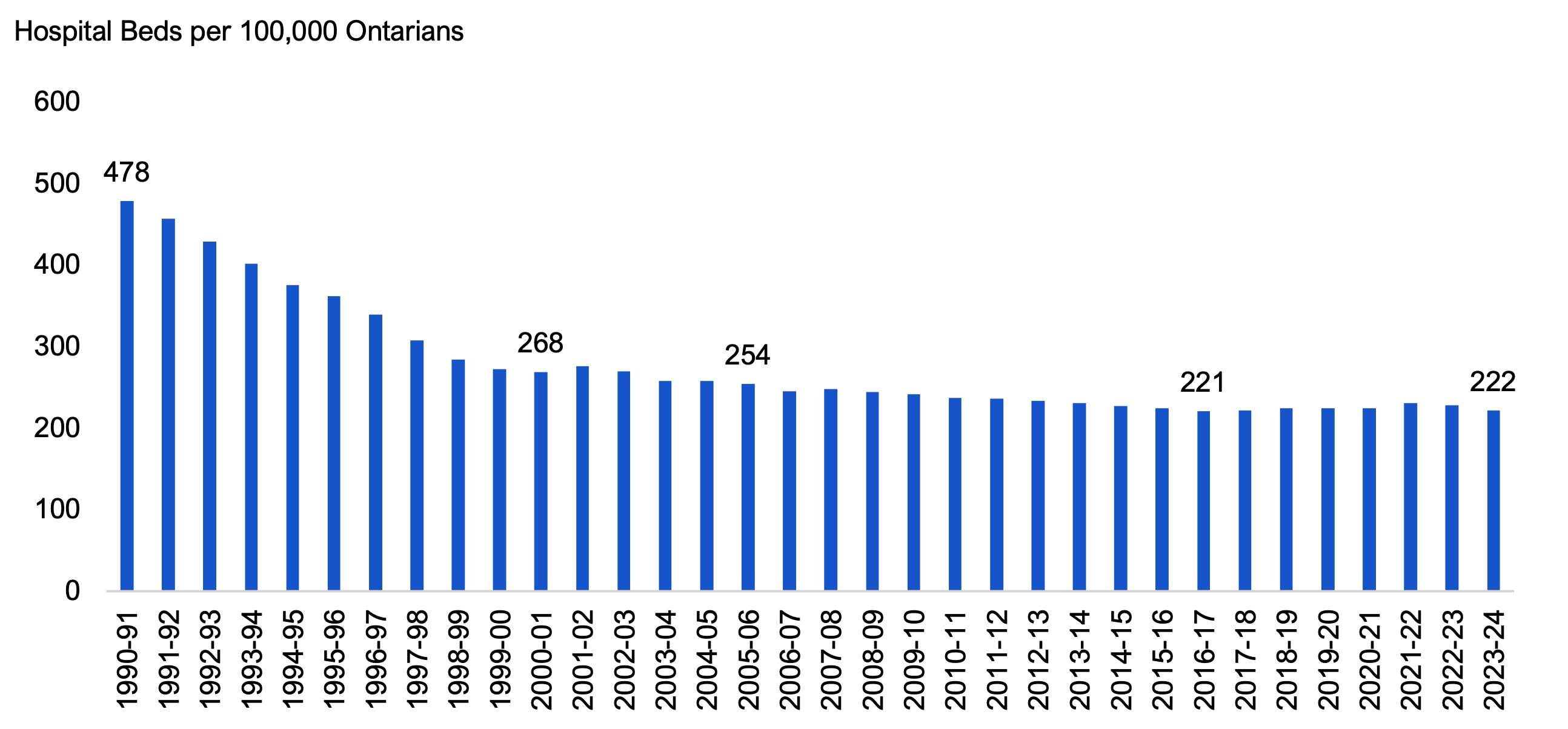

Hospital Beds

In 2023-24, there were 222 hospital beds for every 100,000 Ontarians. This is less than half of the 478 beds per 100,000 Ontarians in 1990-91.[6] This reduction primarily occurred between 1990-91 and 2000-01 as spending restraint in the health sector contributed to significant downsizing of hospitals.[7] The number of hospital beds per 100,000 Ontarians decreased sharply from 478 in 1990-91 to 268 in 2000-01, and more gradually to 254 in 2005-06. Over this period, there was a corresponding reduction in hospital admissions and in the number of days Ontarians spent in hospitals, which reached their lowest points in 2003-04 and 2005-06, respectively.[8] Beyond 2005-06, the number of hospital beds per 100,000 Ontarians continued to decline to a low of 221 in 2016-17, in line with the end of the freeze to hospital global budgets from 2012-13 to 2015-16. From 2016-17 to 2023-24, over 4,000 beds were added and the number of beds per 100,000 Ontarians remained relatively stable, reaching 222 in 2023-24.

Figure 5.4 Number of hospital beds per 100,000 Ontarians, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Province, Statistics Canada, CIHI Trends in Hospital Spending, 2009–2010 to 2022–2023 — Data Tables — Series D: Beds Staffed and In Operation by Functional Centre and Ontario Health Coalition hospital beds staffed and in operation Ontario 1990 to 2014.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Hospital Beds per 100,000 Ontarians |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 478 |

| 1991-92 | 457 |

| 1992-93 | 429 |

| 1993-94 | 402 |

| 1994-95 | 376 |

| 1995-96 | 362 |

| 1996-97 | 339 |

| 1997-98 | 307 |

| 1998-99 | 284 |

| 1999-00 | 272 |

| 2000-01 | 268 |

| 2001-02 | 276 |

| 2002-03 | 270 |

| 2003-04 | 258 |

| 2004-05 | 258 |

| 2005-06 | 254 |

| 2006-07 | 245 |

| 2007-08 | 248 |

| 2008-09 | 244 |

| 2009-10 | 242 |

| 2010-11 | 237 |

| 2011-12 | 236 |

| 2012-13 | 233 |

| 2013-14 | 231 |

| 2014-15 | 227 |

| 2015-16 | 224 |

| 2016-17 | 221 |

| 2017-18 | 222 |

| 2018-19 | 224 |

| 2019-20 | 224 |

| 2020-21 | 224 |

| 2021-22 | 230 |

| 2022-23 | 228 |

| 2023-24 | 222 |

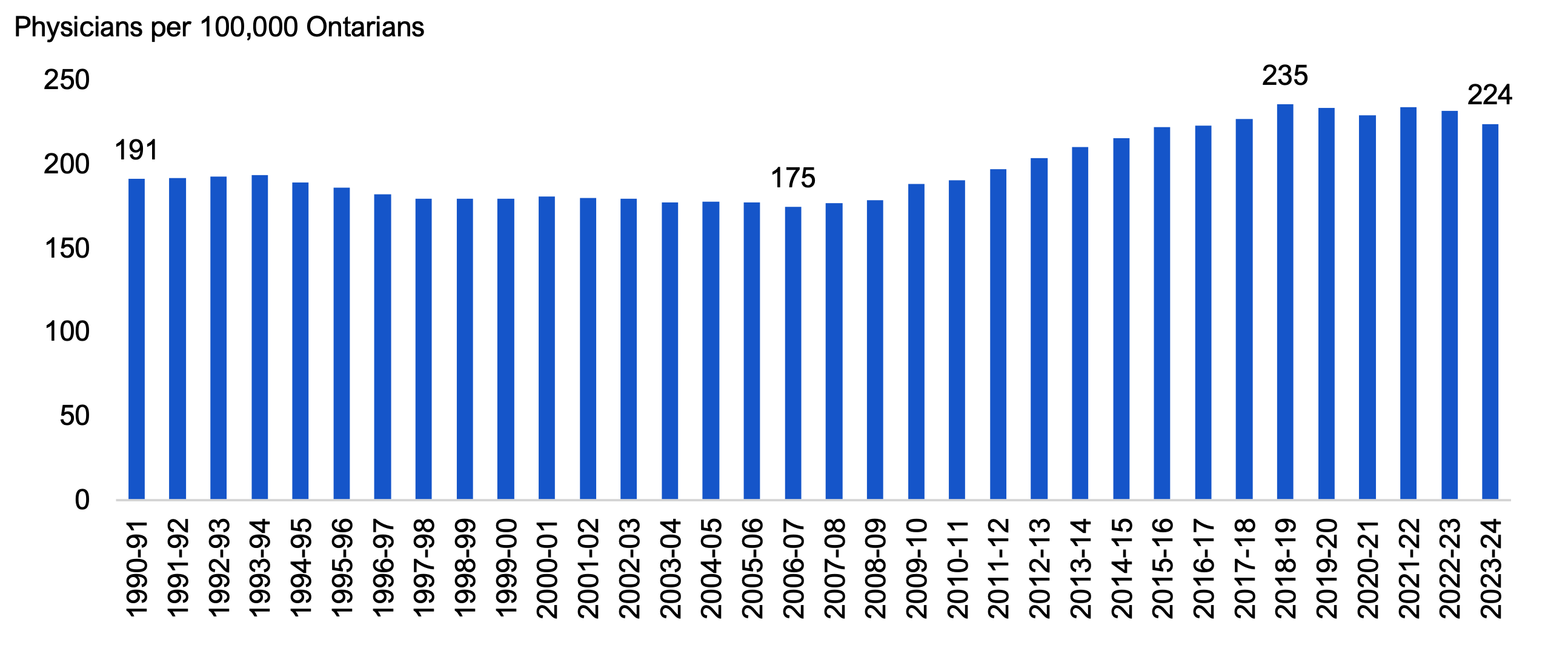

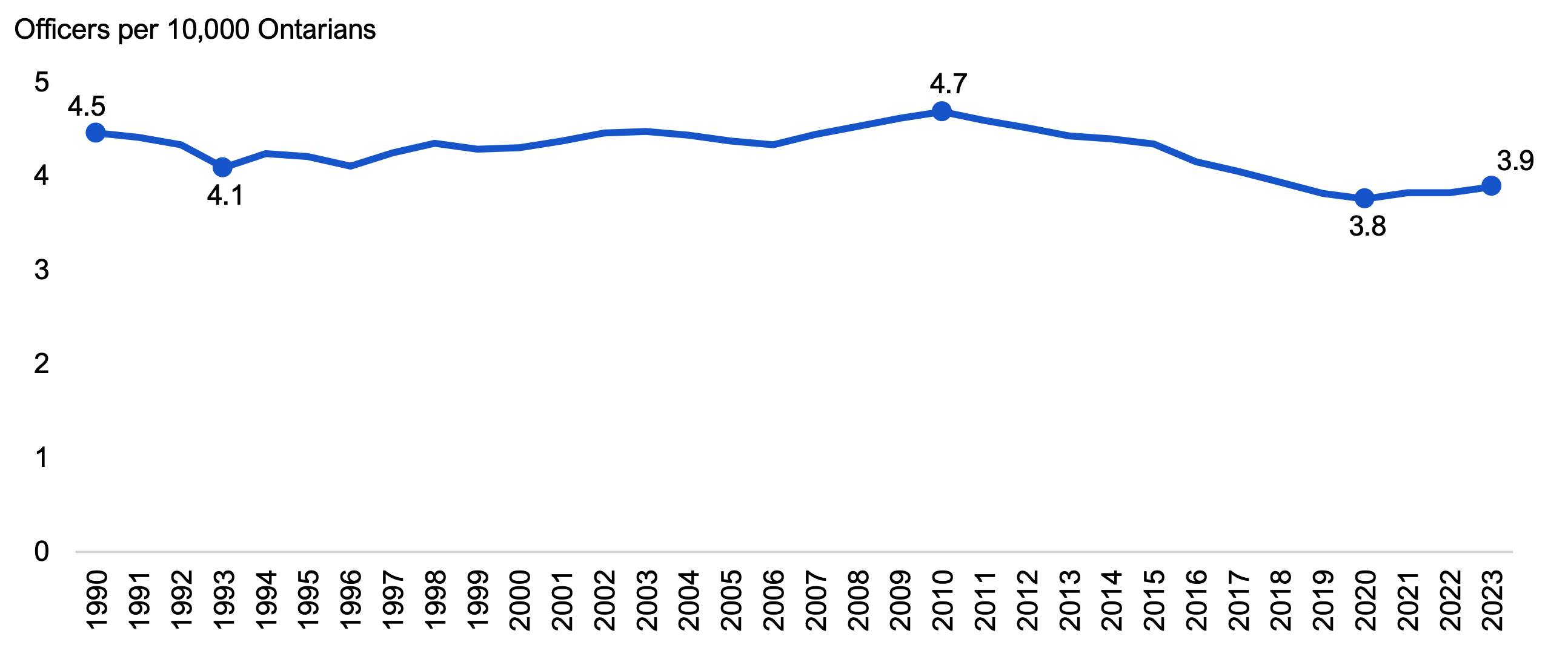

Number of Physicians

In 2023-24, there were 224 physicians for every 100,000 Ontarians. From 1990-91 to 2006-07, Ontario added 2,400 physicians and the number of physicians per 100,000 Ontarians declined from 191 to a low of 175 in 2006-07. However, following efforts to address shortages of physicians, Ontario added over 11,000 physicians from 2006-07 to 2018-19 and the number of physicians per 100,000 Ontarians reached a peak of 235 in 2018-19. From 2018-19 to 2023-24, the number of physicians per 100,000 residents declined to 224, as growth in the number of physicians slowed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 5.5 Number of physicians per 100,000 Ontarians, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO analysis of CIHI National Physician Database Historical Utilization — Data Tables, 2023

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Physicians Per 100,000 Ontarians |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 191 |

| 1991-92 | 192 |

| 1992-93 | 192 |

| 1993-94 | 193 |

| 1994-95 | 189 |

| 1995-96 | 186 |

| 1996-97 | 182 |

| 1997-98 | 179 |

| 1998-99 | 179 |

| 1999-00 | 179 |

| 2000-01 | 180 |

| 2001-02 | 180 |

| 2002-03 | 179 |

| 2003-04 | 177 |

| 2004-05 | 178 |

| 2005-06 | 177 |

| 2006-07 | 175 |

| 2007-08 | 177 |

| 2008-09 | 178 |

| 2009-10 | 188 |

| 2010-11 | 190 |

| 2011-12 | 197 |

| 2012-13 | 203 |

| 2013-14 | 210 |

| 2014-15 | 215 |

| 2015-16 | 222 |

| 2016-17 | 223 |

| 2017-18 | 227 |

| 2018-19 | 235 |

| 2019-20 | 233 |

| 2020-21 | 229 |

| 2021-22 | 234 |

| 2022-23 | 231 |

| 2023-24 | 224 |

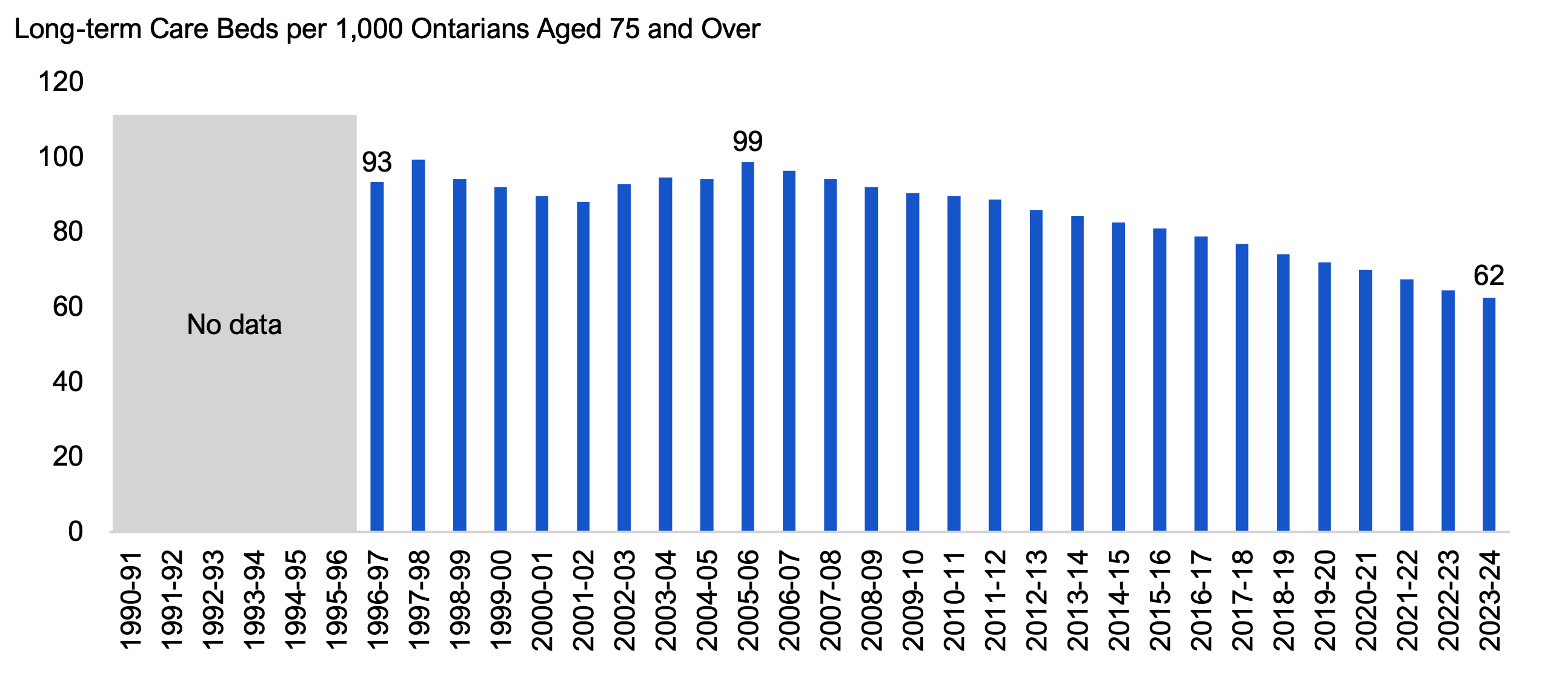

Long-term Care Beds

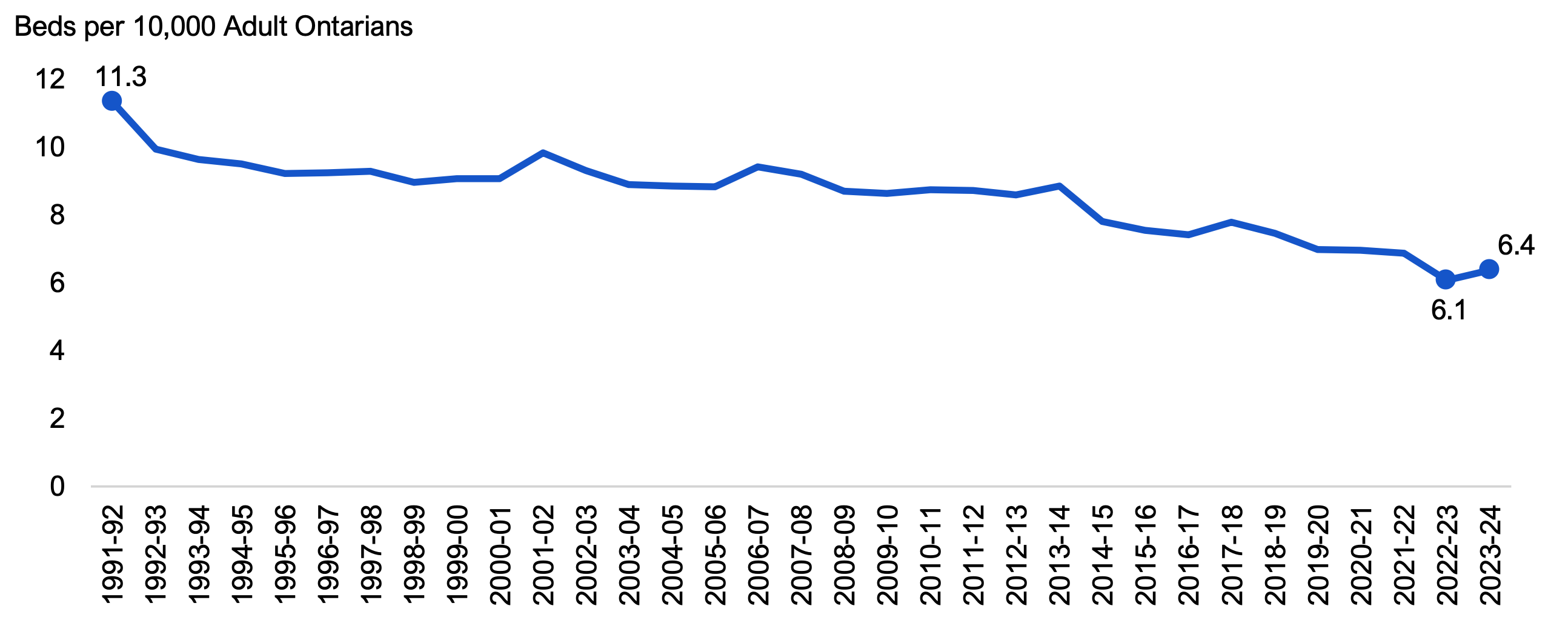

In 2023-24, there were 62 long-term care beds per 1,000 Ontarians aged 75 and over,[9] which was the lowest ratio of beds per population over the analysis period. From 1996-97 to 2005-06, the Province added over 23,000 new long-term care beds, which increased the number of beds per 1,000 Ontarians aged 75 and over to 99 in 2005-06. From 2005-06 to 2023-24, approximately 4,200 new long-term care beds were added. This slow growth in capacity, combined with accelerating growth in the population of Ontarians aged 75 and over, resulted in a steady decline in the number of long-term care beds per 1,000 Ontarians aged 75 and over, from 99 in 2005-06 to 62 in 2023-24.

Figure 5.6 Number of long-term care beds per 1,000 Ontarians aged 75 and over, 1996-97 to 2023-24

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Province, Statistics Canada and Hsu AT, Berta W, Coyte PC, Laporte A. Staffing in Ontario’s Long-Term Care Homes: Differences by Profit Status and Chain Ownership. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement. 2016;35(2):175-189. doi:10.1017/S071498081600019

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Long-term Care Beds Per 1,000 Ontarians Aged 75 and Over |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | No Data |

| 1991-92 | No Data |

| 1992-93 | No Data |

| 1993-94 | No Data |

| 1994-95 | No Data |

| 1995-96 | No Data |

| 1996-97 | 93 |

| 1997-98 | 99 |

| 1998-99 | 94 |

| 1999-00 | 92 |

| 2000-01 | 90 |

| 2001-02 | 88 |

| 2002-03 | 93 |

| 2003-04 | 94 |

| 2004-05 | 94 |

| 2005-06 | 99 |

| 2006-07 | 96 |

| 2007-08 | 94 |

| 2008-09 | 92 |

| 2009-10 | 90 |

| 2010-11 | 90 |

| 2011-12 | 88 |

| 2012-13 | 86 |

| 2013-14 | 84 |

| 2014-15 | 82 |

| 2015-16 | 81 |

| 2016-17 | 79 |

| 2017-18 | 77 |

| 2018-19 | 74 |

| 2019-20 | 72 |

| 2020-21 | 70 |

| 2021-22 | 67 |

| 2022-23 | 64 |

| 2023-24 | 62 |

6. Education

Spending Trends

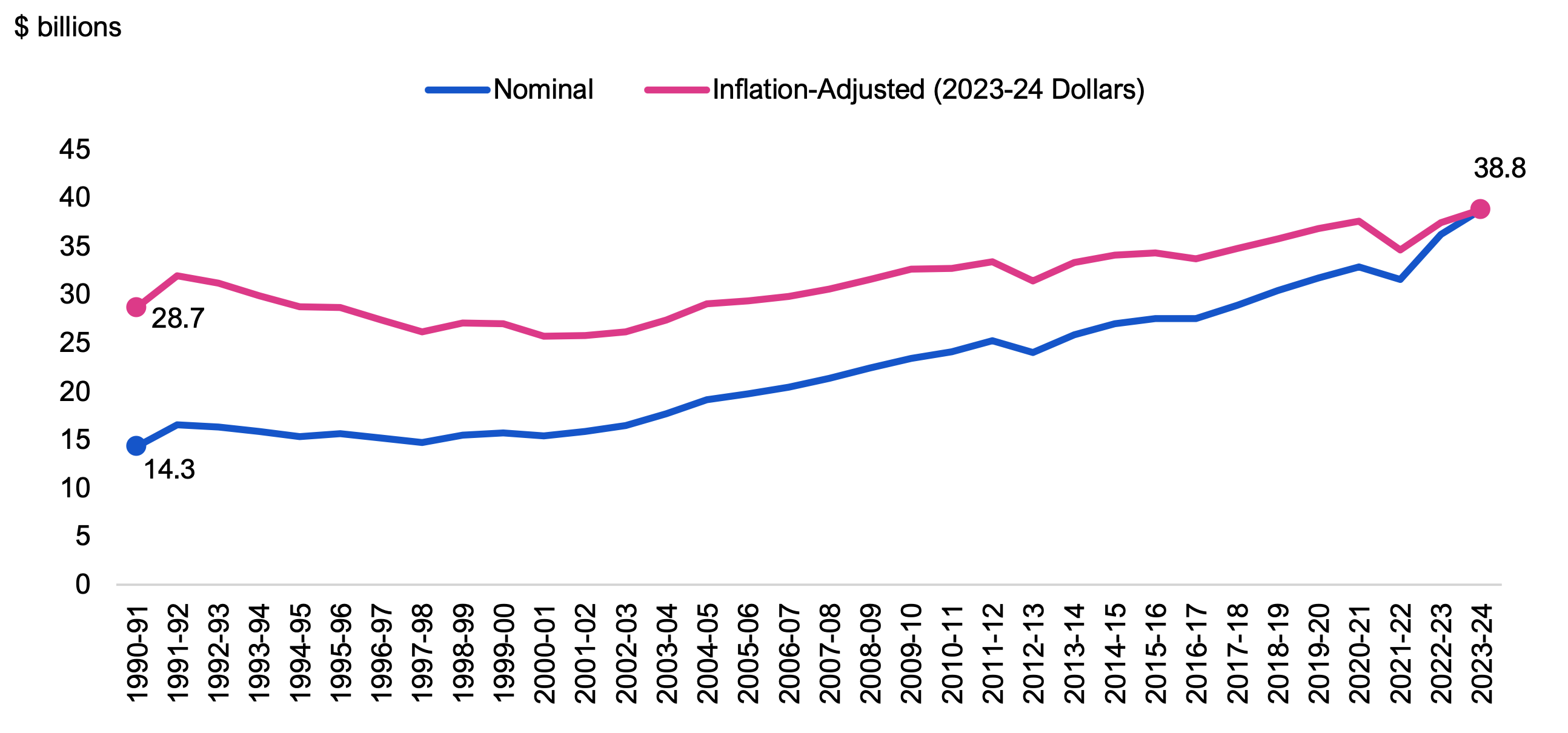

Education is the second largest sector in the government, accounting for 18.8 per cent of total spending in 2023-24. This sector primarily consists of spending on elementary and secondary education, and child care.[10] The FAO estimates education sector spending grew at an average annual rate of 3.1 per cent, increasing from $14.3 billion in 1990-91 to $38.8 billion in 2023-24. After adjusting for inflation, this sector’s spending grew at an average annual rate of 0.9 per cent from 1990-91 to 2023-24.

Figure 6.1 Education sector spending, nominal and inflation-adjusted, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Nominal | Inflation-Adjusted (2023-24 Dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 14.3 | 28.7 |

| 1991-92 | 16.5 | 31.9 |

| 1992-93 | 16.3 | 31.2 |

| 1993-94 | 15.9 | 29.9 |

| 1994-95 | 15.3 | 28.8 |

| 1995-96 | 15.6 | 28.7 |

| 1996-97 | 15.2 | 27.4 |

| 1997-98 | 14.8 | 26.2 |

| 1998-99 | 15.5 | 27.1 |

| 1999-00 | 15.7 | 27.0 |

| 2000-01 | 15.4 | 25.7 |

| 2001-02 | 15.9 | 25.8 |

| 2002-03 | 16.5 | 26.2 |

| 2003-04 | 17.7 | 27.3 |

| 2004-05 | 19.1 | 29.1 |

| 2005-06 | 19.8 | 29.4 |

| 2006-07 | 20.4 | 29.8 |

| 2007-08 | 21.3 | 30.6 |

| 2008-09 | 22.4 | 31.6 |

| 2009-10 | 23.4 | 32.6 |

| 2010-11 | 24.1 | 32.7 |

| 2011-12 | 25.2 | 33.4 |

| 2012-13 | 24.0 | 31.4 |

| 2013-14 | 25.8 | 33.3 |

| 2014-15 | 27.0 | 34.1 |

| 2015-16 | 27.5 | 34.3 |

| 2016-17 | 27.5 | 33.7 |

| 2017-18 | 28.9 | 34.8 |

| 2018-19 | 30.4 | 35.8 |

| 2019-20 | 31.7 | 36.8 |

| 2020-21 | 32.9 | 37.6 |

| 2021-22 | 31.6 | 34.6 |

| 2022-23 | 36.2 | 37.4 |

| 2023-24 | 38.8 | 38.8 |

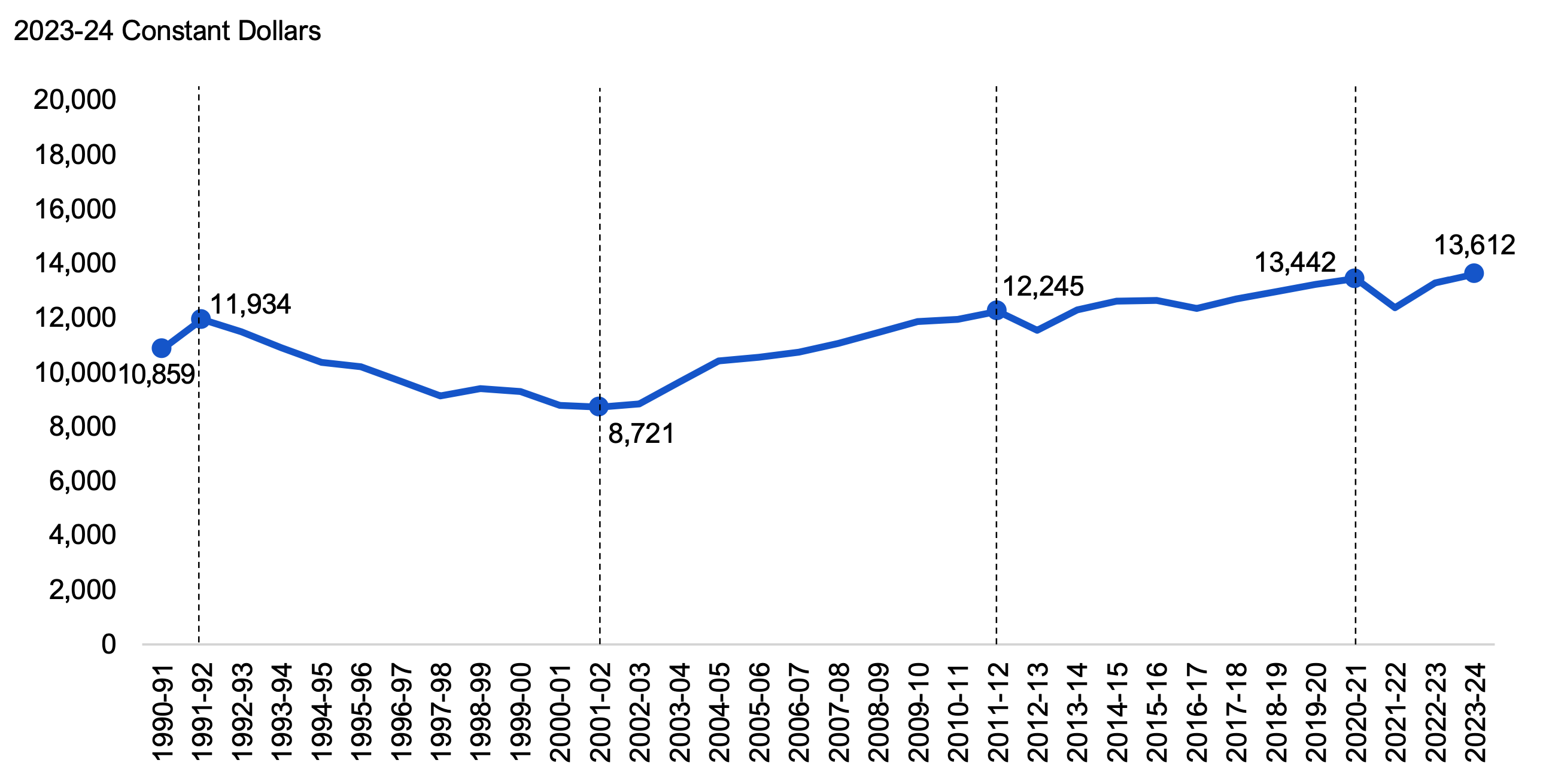

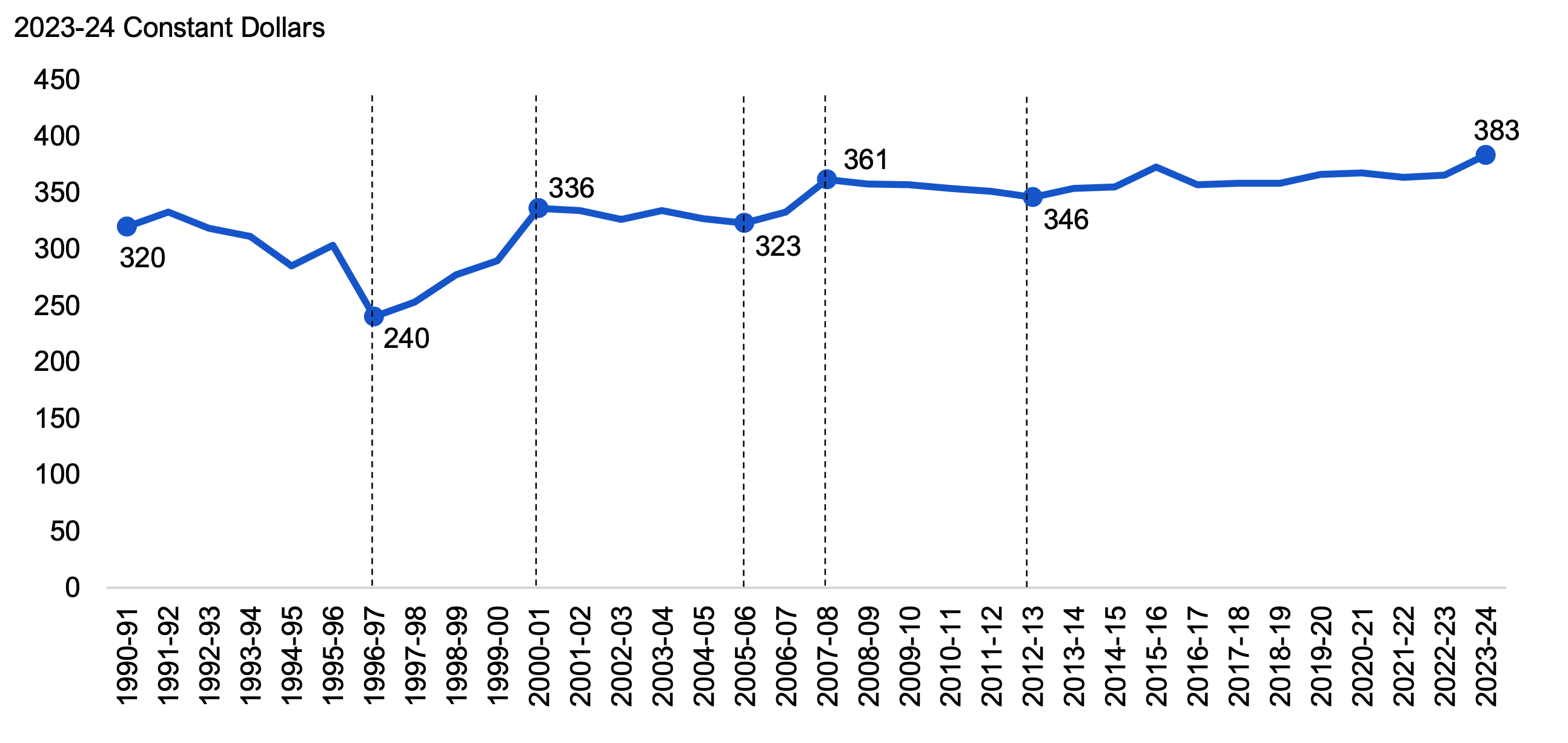

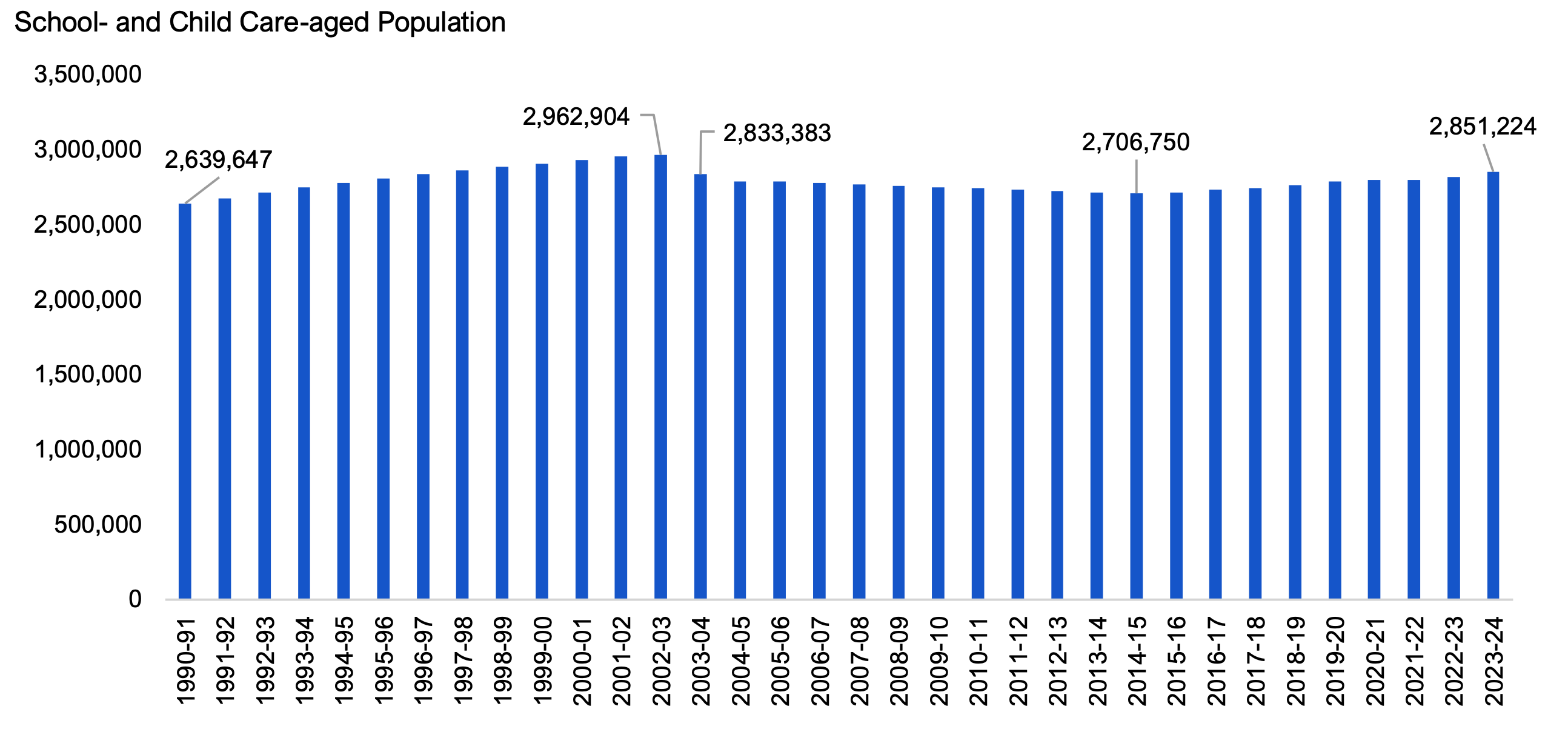

In addition to inflation, an important cost driver of education sector spending is the school- and child care-aged population.[11] The following presents education sector spending on an inflation-adjusted (i.e., real) per child/youth basis to provide a better indication of the impact that education sector spending has on service levels over time. The FAO estimates real per child/youth education sector spending increased at an average annual rate of 0.7 per cent from $10,859 per child/youth in 1990-91 to $13,612 per child/youth in 2023-24.

Figure 6.2 Education sector spending per school- and child care-aged child and youth, inflation-adjusted, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Note: From 1990-91 to 2002-03, the school- and child care-aged population reflects the population of 0- to 18-year-olds. After the phase-out of the Ontario Academic Credit (OAC) fifth year of secondary school education, beginning in 2003-04, this age group reflects the population of 0- to 17-year-olds.

Source: FAO calculations, Public Accounts of Ontario, Statistics Canada and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Real Per Child/Youth Spending |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 10,859 |

| 1991-92 | 11,934 |

| 1992-93 | 11,485 |

| 1993-94 | 10,904 |

| 1994-95 | 10,364 |

| 1995-96 | 10,215 |

| 1996-97 | 9,658 |

| 1997-98 | 9,147 |

| 1998-99 | 9,396 |

| 1999-00 | 9,295 |

| 2000-01 | 8,780 |

| 2001-02 | 8,721 |

| 2002-03 | 8,836 |

| 2003-04 | 9,652 |

| 2004-05 | 10,424 |

| 2005-06 | 10,559 |

| 2006-07 | 10,745 |

| 2007-08 | 11,054 |

| 2008-09 | 11,462 |

| 2009-10 | 11,876 |

| 2010-11 | 11,947 |

| 2011-12 | 12,245 |

| 2012-13 | 11,547 |

| 2013-14 | 12,296 |

| 2014-15 | 12,604 |

| 2015-16 | 12,653 |

| 2016-17 | 12,361 |

| 2017-18 | 12,692 |

| 2018-19 | 12,968 |

| 2019-20 | 13,219 |

| 2020-21 | 13,442 |

| 2021-22 | 12,367 |

| 2022-23 | 13,294 |

| 2023-24 | 13,612 |

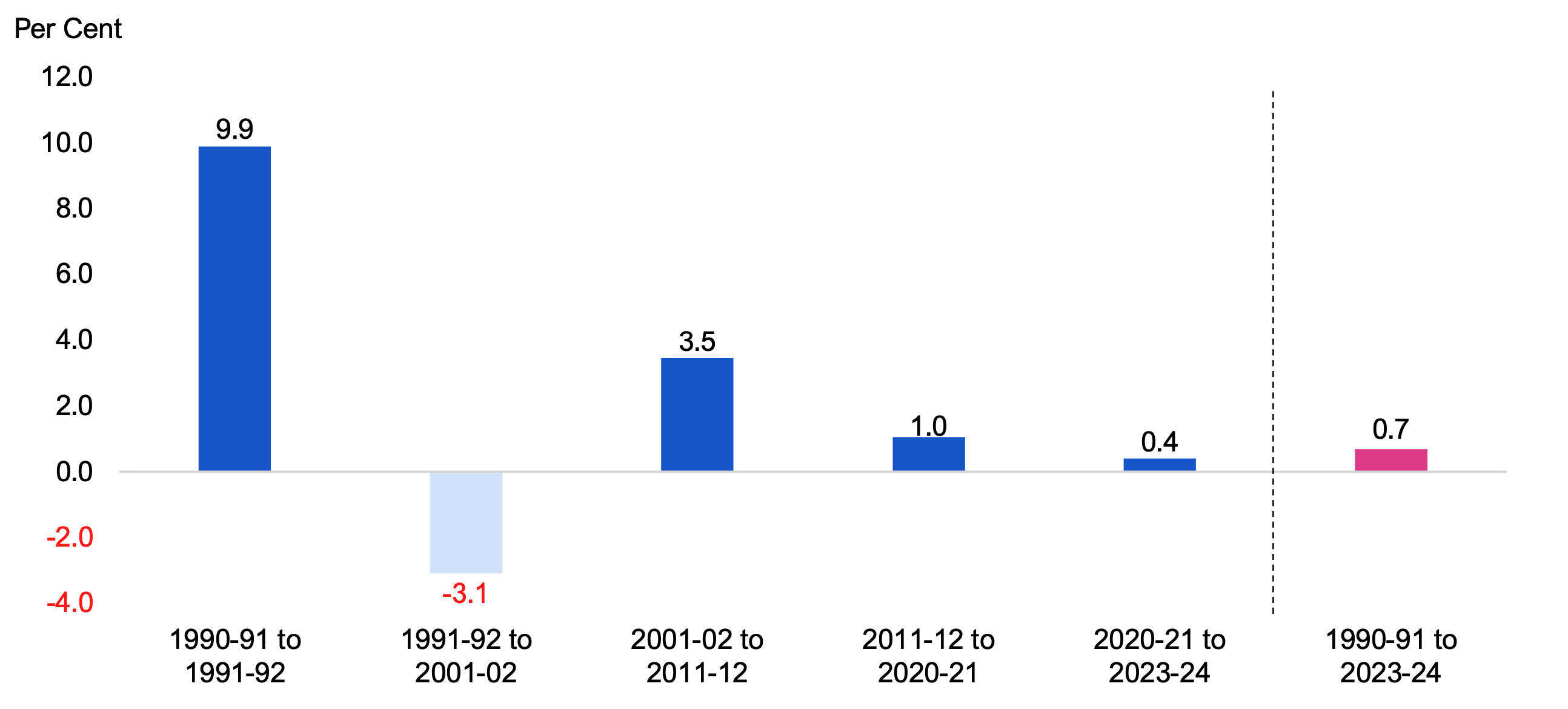

Based on real per child/youth spending, the FAO has identified five distinct periods of education sector spending trends between 1990-91 to 2023-24:

1990-91 to 1991-92

From 1990-91 to 1991-92, real spending per child/youth increased by 9.9 per cent from $10,859 in 1990-91 to $11,934 in 1991-92. This increase was primarily due to increased funding for school boards and contributions to the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan.

1991-92 to 2001-02

From 1991-92 to 2001-02, real spending per child/youth decreased from $11,934 in 1991-92 to $8,721 in 2001-02 at an average annual rate of -3.1 per cent. During this period, the government introduced fiscal restraint measures that kept growth in nominal education spending relatively flat while the school- and child care-aged population grew significantly (see Appendix B).

2001-02 to 2011-12

From 2001-02 to 2011-12, real spending per child/youth grew from $8,721 to $12,245 at an average annual rate of 3.5 per cent. This growth was driven by government policy introduced in 2004 to cap class sizes at 20 students for Junior Kindergarten (JK) through Grade 3. Furthermore, the Province launched the Best Start plan in 2005 to enhance early childhood education and add 25,000 new child care spaces.

2011-12 to 2020-21

From 2011-12 to 2020-21, real spending per child/youth grew from $12,245 to $13,442 at an average annual rate of 1.0 per cent. This period was characterized by increased spending in child care and the implementation of Full Day Kindergarten in 2014-15. This increased spending was partially offset by slower growth in elementary and secondary education spending.

2020-21 to 2023-24

From 2020-21 to 2023-24, real spending per child/youth fluctuated but ultimately increased at an average annual rate of 0.4 per cent, to $13,612 in 2023-24. Spending initially declined in 2021-22 due to the expiry of time-limited spending related to the COVID-19 pandemic, before increasing in 2022-23, largely due to the introduction of the Canada Wide Early Learning and Child Care Agreement (CWELCC).[12] Additionally, in 2022-23 and 2023-24, the Province recorded expenses for retroactive compensation related to Bill 124, the Protecting a Sustainable Public Sector for Future Generations Act, 2019.

Figure 6.3 Average annual growth in real per child/youth education sector spending, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Note: From 1990-91 to 2002-03, the school- and child care-aged population reflects the population of 0- to 18-year-olds. After the phase-out of the Ontario Academic Credit (OAC) fifth year of secondary school education, beginning in 2003-04, this age group reflects the population of 0- to 17-year-olds

Source: FAO calculations, Public Accounts of Ontario, Statistics Canada and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Years | 1990-91 to 1991-92 | 1991-92 to 2001-02 | 2001-02 to 2011-12 | 2011-12 to 2020-21 | 2020-21 to 2023-24 | 1990-91 to 2023-24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Annual Growth | 9.9 | -3.1 | 3.5 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

Select Service Levels

In this section, the FAO analyzes two key service level trends: average number of students per teacher and the number of licensed child care centre spaces per child care-aged population. There are many other measures of education sector service levels and performance. For more information, see FAO, Ontario School Boards: Enrolment, Finances and Student Outcomes; Ministry of Education, Ontario’s Early Years and Child Care Annual Report 2024; and EQAO, EQAO Assessment Results for 2023–2024 School Year.

Student-to-Teacher Ratio

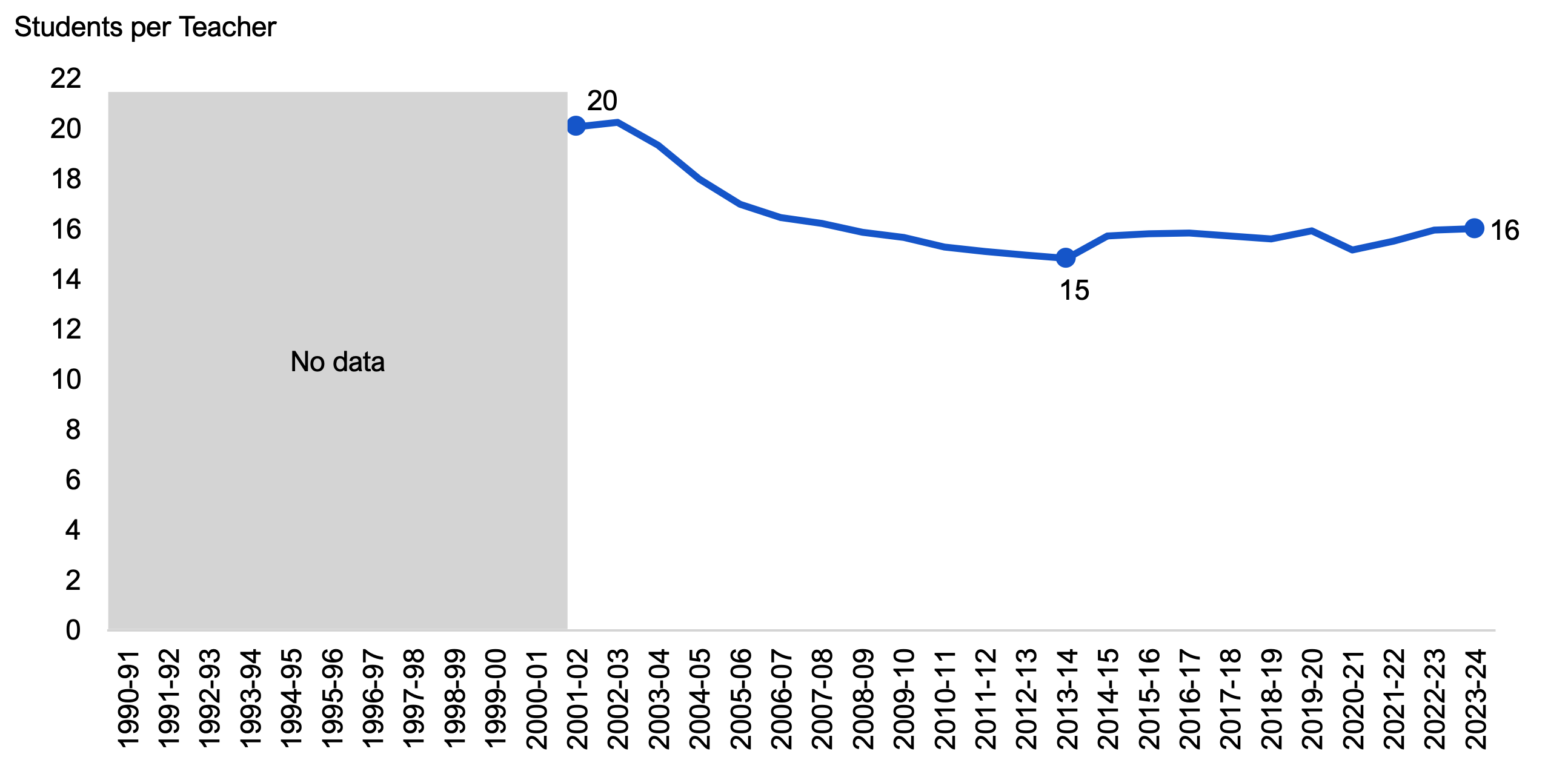

Over the period from 2001-02 to 2023-24, the student-to-teacher ratio fell from 20 in 2001-02 to 16 in 2023-24.[13] The ratio began to decline steeply in 2004-05 as a result of measures to reduce class sizes announced in 2004-05 and reached a low of 15 in 2013-14. After 2013-14, the ratio remained relatively stable, with a student-to-teacher ratio of 16 in 2023-24.

Figure 6.4 Average number of students per teacher in Ontario, 2001-02 to 2023-24

Note: The student-to-teacher ratio reflects teacher FTEs for the 2010-11 to 2023-24 school years. For 2001-02 to 2009-10, the student-to-teacher ratio is an FAO estimate based on Statistics Canada salaried education workers data.

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Students Per Teacher |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | No Data |

| 1991-92 | No Data |

| 1992-93 | No Data |

| 1993-94 | No Data |

| 1994-95 | No Data |

| 1995-96 | No Data |

| 1996-97 | No Data |

| 1997-98 | No Data |

| 1998-99 | No Data |

| 1999-00 | No Data |

| 2000-01 | No Data |

| 2001-02 | 20 |

| 2002-03 | 20 |

| 2003-04 | 19 |

| 2004-05 | 18 |

| 2005-06 | 17 |

| 2006-07 | 16 |

| 2007-08 | 16 |

| 2008-09 | 16 |

| 2009-10 | 16 |

| 2010-11 | 15 |

| 2011-12 | 15 |

| 2012-13 | 15 |

| 2013-14 | 15 |

| 2014-15 | 16 |

| 2015-16 | 16 |

| 2016-17 | 16 |

| 2017-18 | 16 |

| 2018-19 | 16 |

| 2019-20 | 16 |

| 2020-21 | 15 |

| 2021-22 | 16 |

| 2022-23 | 16 |

| 2023-24 | 16 |

Child Care Spaces

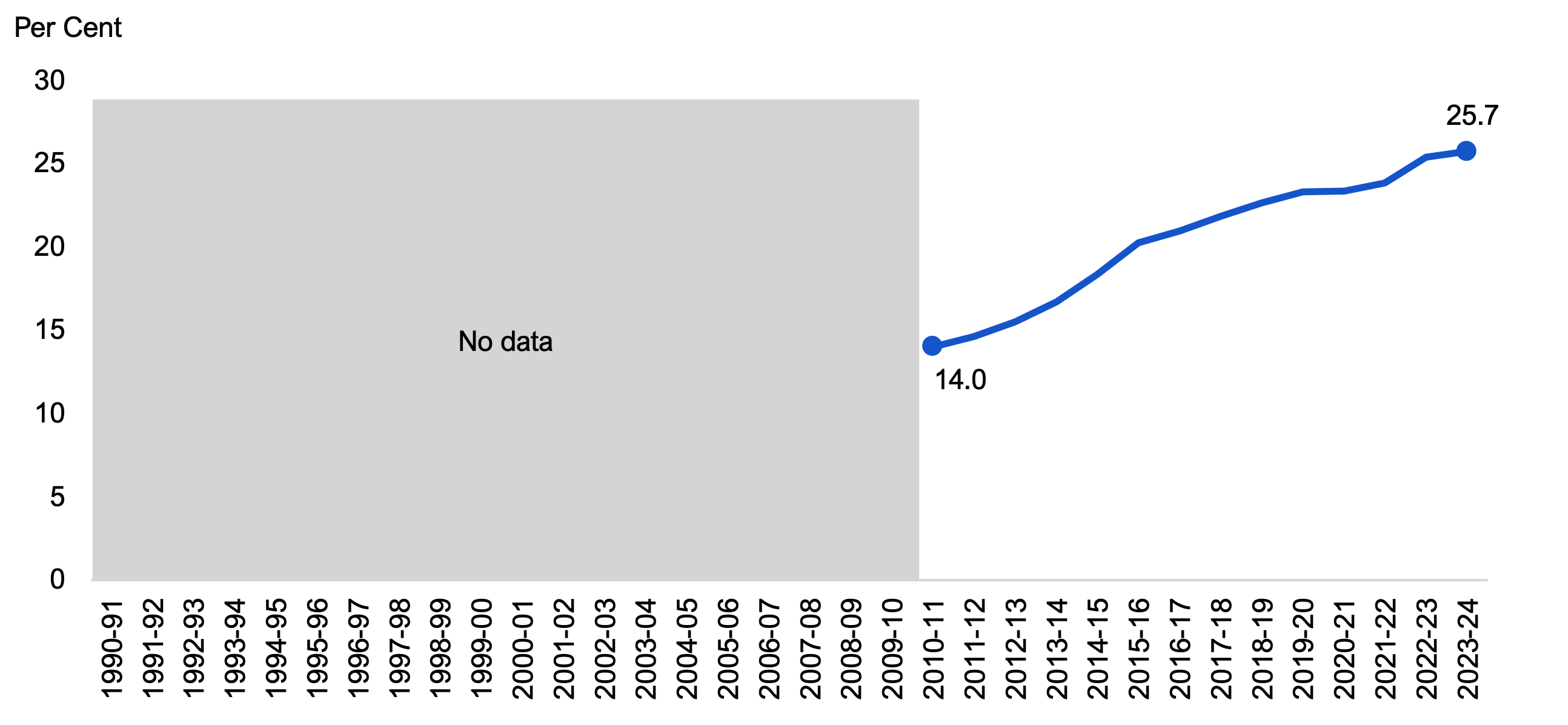

From 2010-11 to 2023-24, growth in the number of licensed child care spaces in Ontario has significantly outpaced growth in the child care-aged population. Over this period, the number of licensed child care centre spaces grew at an average annual rate of 5.3 per cent compared to average annual growth in the child care-aged population of 0.5 per cent. Consequently, the number of licensed child care centre spaces as a share of the child care-aged population increased from 14.0 per cent in 2010-11 to 25.7 per cent in 2023-24.

Figure 6.5 Licensed child care centre spaces as a share of the child care-aged population, 2010-11 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Licensed Child Care Centre Spaces as a Share of the Child Care-aged Population |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | No Data |

| 1991-92 | No Data |

| 1992-93 | No Data |

| 1993-94 | No Data |

| 1994-95 | No Data |

| 1995-96 | No Data |

| 1996-97 | No Data |

| 1997-98 | No Data |

| 1998-99 | No Data |

| 1999-00 | No Data |

| 2000-01 | No Data |

| 2001-02 | No Data |

| 2002-03 | No Data |

| 2003-04 | No Data |

| 2004-05 | No Data |

| 2005-06 | No Data |

| 2006-07 | No Data |

| 2007-08 | No Data |

| 2008-09 | No Data |

| 2009-10 | No Data |

| 2010-11 | 14.0 |

| 2011-12 | 14.6 |

| 2012-13 | 15.5 |

| 2013-14 | 16.7 |

| 2014-15 | 18.4 |

| 2015-16 | 20.3 |

| 2016-17 | 21.0 |

| 2017-18 | 21.9 |

| 2018-19 | 22.7 |

| 2019-20 | 23.3 |

| 2020-21 | 23.4 |

| 2021-22 | 23.9 |

| 2022-23 | 25.4 |

| 2023-24 | 25.7 |

7. Postsecondary Education

Spending Trends

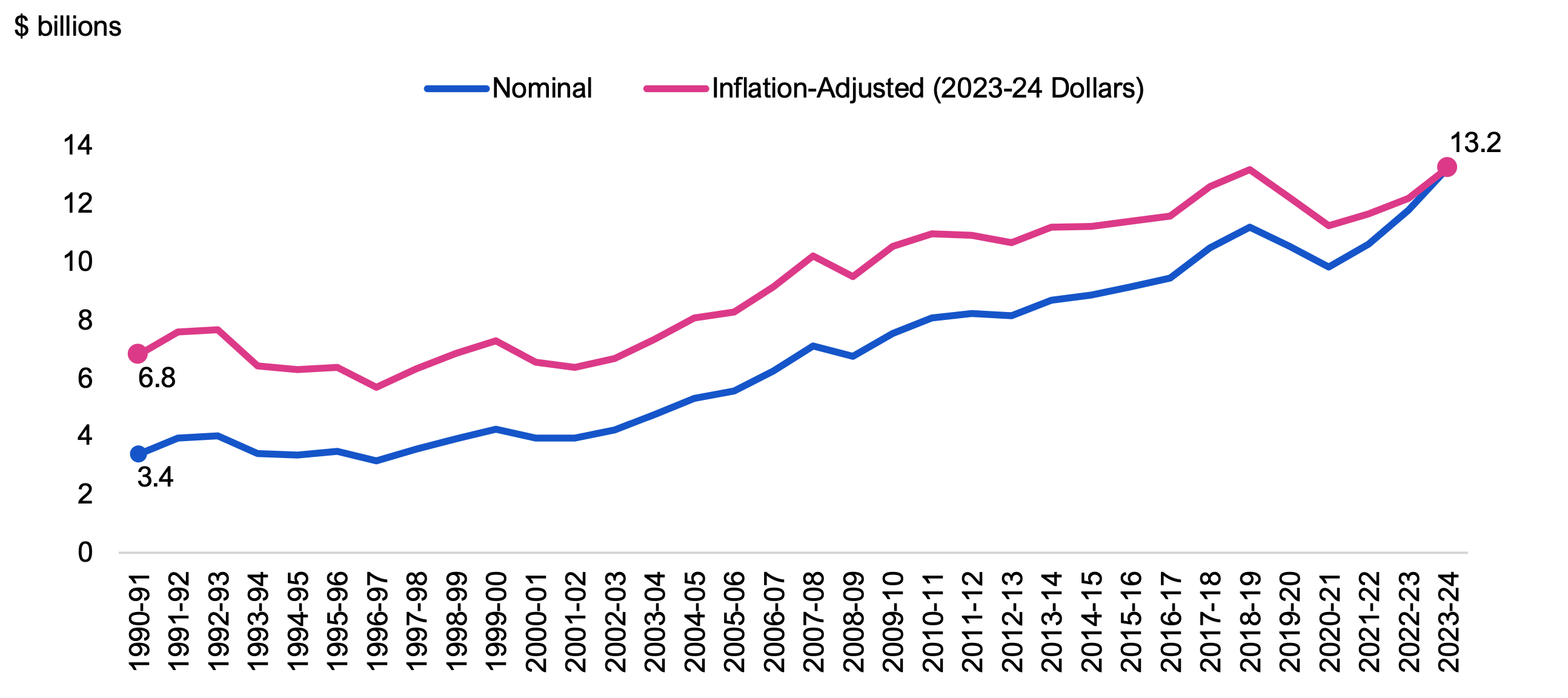

Postsecondary education is the fifth largest sector in the government, accounting for 6.4 per cent of total spending in 2023-24. This sector primarily consists of consolidated spending by colleges, transfer payments to universities and spending on student financial assistance. The FAO estimates postsecondary education sector spending grew at an average annual rate of 4.2 per cent from $3.4 billion in 1990-91 to $13.2 billion in 2023-24. After adjusting for inflation, this sector’s spending increased at an average annual rate of 2.0 per cent from 1990-91 to 2023-24.

Figure 7.1 Postsecondary education sector spending, nominal and inflation-adjusted, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Nominal | Inflation-Adjusted (2023-24 Dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 3.4 | 6.8 |

| 1991-92 | 3.9 | 7.6 |

| 1992-93 | 4.0 | 7.7 |

| 1993-94 | 3.4 | 6.4 |

| 1994-95 | 3.4 | 6.3 |

| 1995-96 | 3.5 | 6.4 |

| 1996-97 | 3.2 | 5.7 |

| 1997-98 | 3.6 | 6.3 |

| 1998-99 | 3.9 | 6.9 |

| 1999-00 | 4.3 | 7.3 |

| 2000-01 | 3.9 | 6.5 |

| 2001-02 | 3.9 | 6.4 |

| 2002-03 | 4.2 | 6.7 |

| 2003-04 | 4.7 | 7.3 |

| 2004-05 | 5.3 | 8.1 |

| 2005-06 | 5.6 | 8.3 |

| 2006-07 | 6.2 | 9.1 |

| 2007-08 | 7.1 | 10.2 |

| 2008-09 | 6.7 | 9.5 |

| 2009-10 | 7.5 | 10.5 |

| 2010-11 | 8.1 | 11.0 |

| 2011-12 | 8.2 | 10.9 |

| 2012-13 | 8.2 | 10.7 |

| 2013-14 | 8.7 | 11.2 |

| 2014-15 | 8.9 | 11.2 |

| 2015-16 | 9.1 | 11.4 |

| 2016-17 | 9.4 | 11.6 |

| 2017-18 | 10.5 | 12.6 |

| 2018-19 | 11.2 | 13.2 |

| 2019-20 | 10.5 | 12.2 |

| 2020-21 | 9.8 | 11.2 |

| 2021-22 | 10.6 | 11.6 |

| 2022-23 | 11.8 | 12.2 |

| 2023-24 | 13.2 | 13.2 |

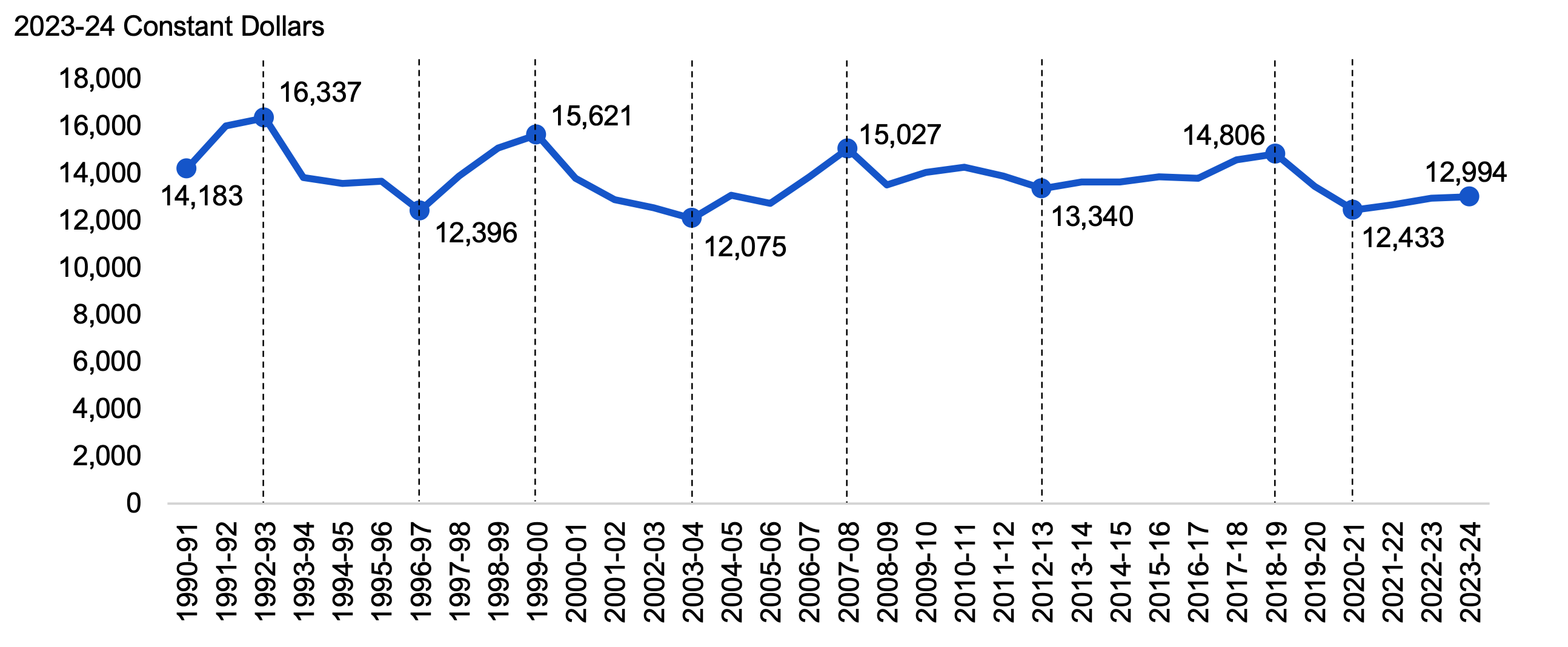

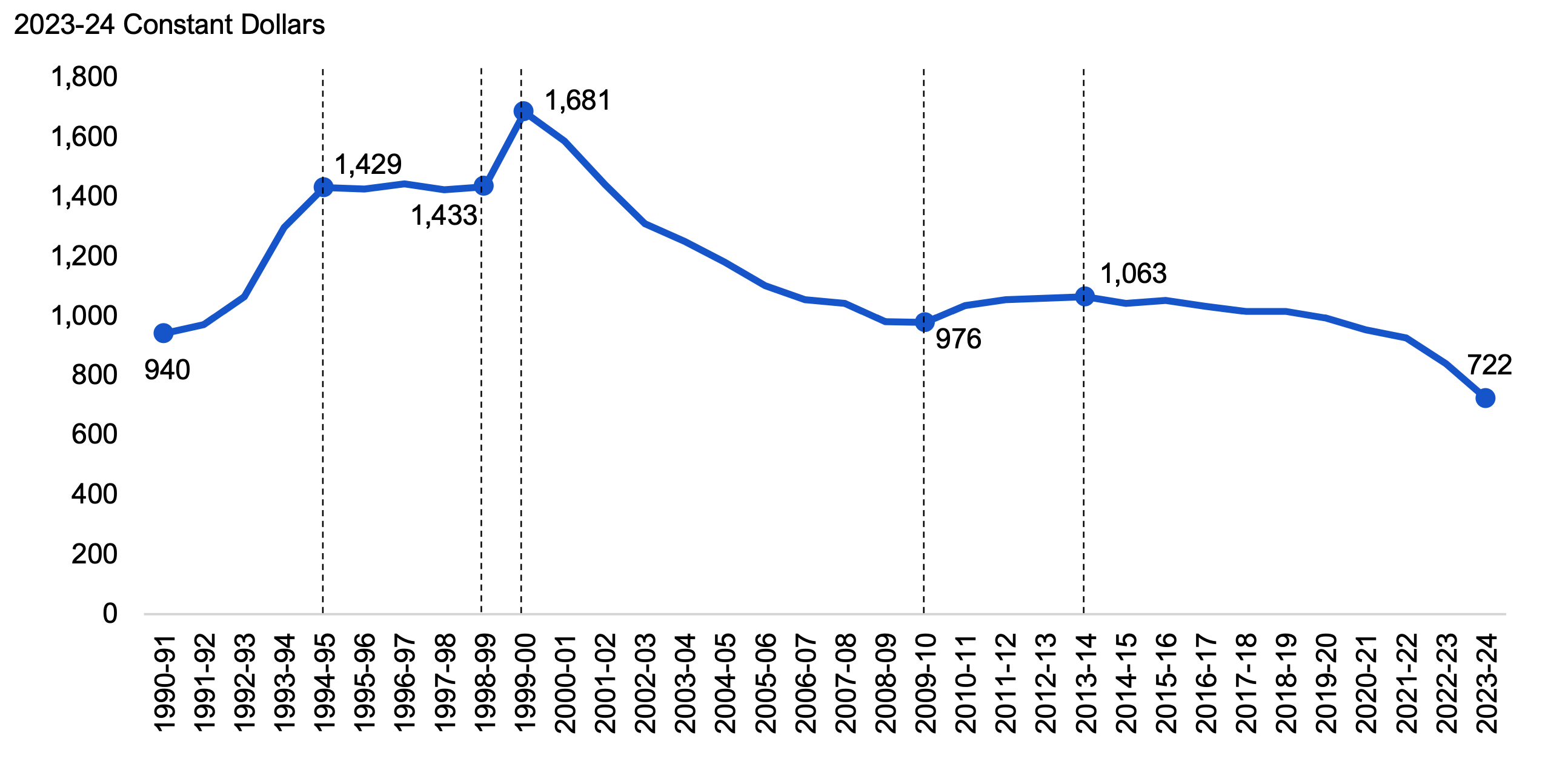

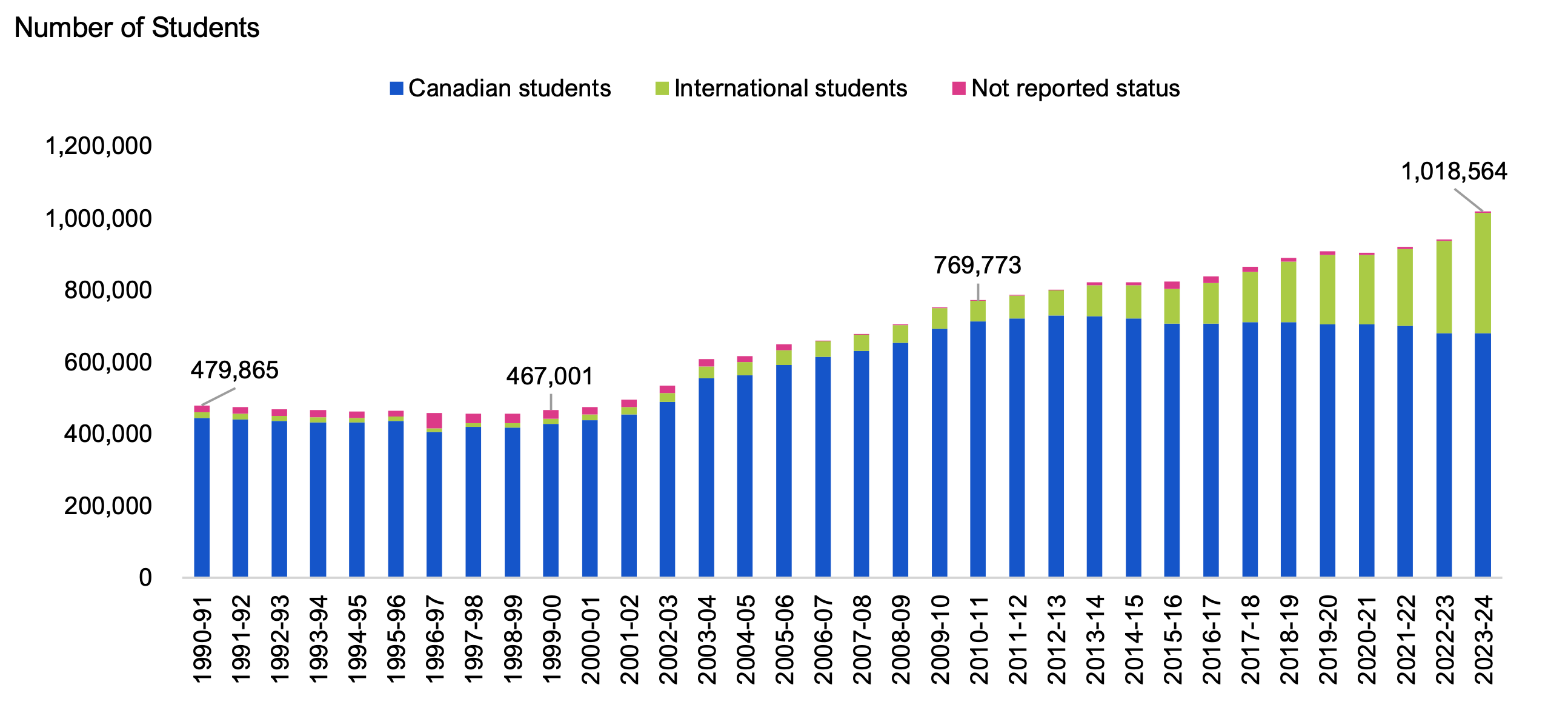

In addition to inflation, an important cost driver of postsecondary education sector spending is student enrolment in colleges and universities.[14] The following presents postsecondary education sector spending on an inflation-adjusted (i.e., real) per student basis to provide a better indication of the impact that postsecondary education spending has on service levels over time. The FAO estimates that real postsecondary education spending per student decreased at an average annual rate of -0.3 per cent from $14,183 in 1990-91 to $12,994 in 2023-24.

Figure 7.2 Postsecondary education sector spending per student, inflation-adjusted, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Real Per Student Spending |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 14,183 |

| 1991-92 | 16,009 |

| 1992-93 | 16,337 |

| 1993-94 | 13,808 |

| 1994-95 | 13,575 |

| 1995-96 | 13,665 |

| 1996-97 | 12,396 |

| 1997-98 | 13,874 |

| 1998-99 | 15,061 |

| 1999-00 | 15,621 |

| 2000-01 | 13,786 |

| 2001-02 | 12,882 |

| 2002-03 | 12,518 |

| 2003-04 | 12,075 |

| 2004-05 | 13,062 |

| 2005-06 | 12,732 |

| 2006-07 | 13,854 |

| 2007-08 | 15,027 |

| 2008-09 | 13,499 |

| 2009-10 | 14,029 |

| 2010-11 | 14,249 |

| 2011-12 | 13,883 |

| 2012-13 | 13,340 |

| 2013-14 | 13,633 |

| 2014-15 | 13,621 |

| 2015-16 | 13,834 |

| 2016-17 | 13,786 |

| 2017-18 | 14,563 |

| 2018-19 | 14,806 |

| 2019-20 | 13,435 |

| 2020-21 | 12,433 |

| 2021-22 | 12,646 |

| 2022-23 | 12,942 |

| 2023-24 | 12,994 |

Based on real per student spending, the FAO has identified nine distinct periods of postsecondary education sector spending between 1990-91 to 2023-24:

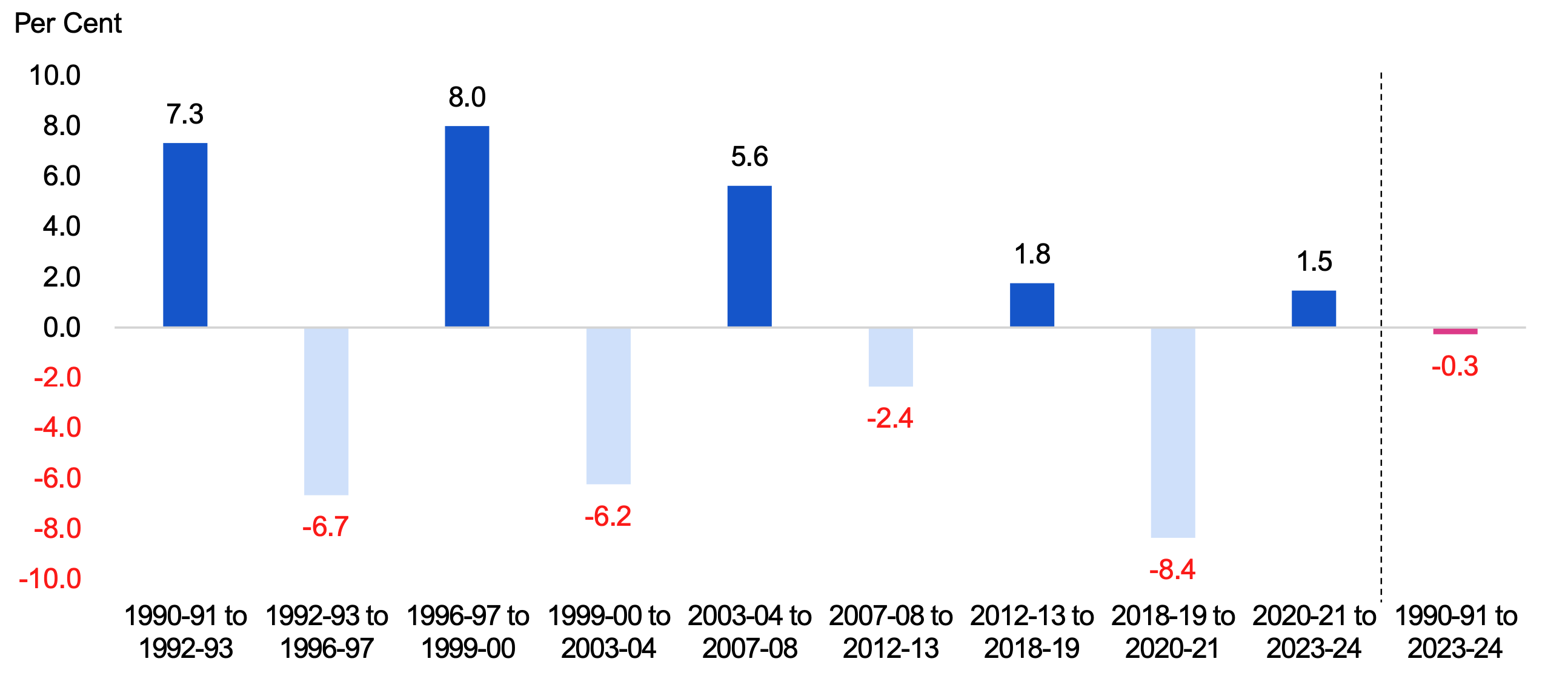

1990-91 to 1992-93

From 1990-91 to 1992-93, real postsecondary education spending per student increased from $14,183 to $16,337 at an average annual rate of 7.3 per cent. This period was characterized by declining enrolment, which decreased by a total of 2.2 per cent over the two-year period.

1992-93 to 1996-97

From 1992-93 to 1996-97, real postsecondary education spending per student declined from $16,337 to $12,396 at an average annual rate of -6.7 per cent. This period was characterized by reductions in government operating grants to universities and colleges.

1996-97 to 1999-00

From 1996-97 to 1999-00, real postsecondary education spending per student increased from $12,396 to $15,621 at an average annual rate of 8.0 per cent. This period was characterized by rapid growth in tuition fees, which increased provincial spending on student financial assistance and funded higher consolidated spending by colleges.

1999-00 to 2003-04

From 1999-00 to 2003-04, real postsecondary education spending per student declined from $15,621 to $12,075 at an average annual rate of -6.2 per cent. This decline was driven by the expansion of federal government support for student financial assistance programs, which reduced provincial spending on provincial student financial assistance (see the Select Service Levels section below for more information).

2003-04 to 2007-08

From 2003-04 to 2007-08, real per student postsecondary education spending grew from $12,075 to $15,027 at an average annual rate of 5.6 per cent. This spending growth was driven by the introduction of the Reaching Higher Plan in 2005, which provided additional funding to postsecondary institutions to add more faculty and increased spending on student financial assistance.

2007-08 to 2012-13

From 2007-08 to 2012-13, real postsecondary education spending per student declined from $15,027 to $13,340 at an average annual rate of -2.4 per cent. This decline was driven by the expiration of one-time capital funding for universities, and strong international student enrolment growth that averaged 8.9 per cent annually, which outpaced spending growth.

2012-13 to 2018-19

From 2012-13 to 2018-19, real per student postsecondary education spending increased from $13,340 to $14,806 at an average annual rate of 1.8 per cent. This spending growth was driven by increased spending on student financial assistance near the end of the period, including government policy to provide free tuition for eligible domestic students, a shift towards providing more support through grants over loans and expanded eligibility.

2018-19 to 2020-21

From 2018-19 to 2020-21, real postsecondary education spending per student declined from $14,806 to $12,433 at an average annual rate of -8.4 per cent. This decline was largely driven by reduced student financial assistance spending, including the removal of free tuition for eligible domestic students, a 10 per cent reduction in tuition fees for domestic students, which lowered student financial assistance costs, and increased federal student financial assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic, which lowered provincial student financial assistance spending. The reduction in tuition fees also slowed growth in consolidated spending by colleges at the beginning of the period.

2020-21 to 2023-24

From 2020-21 to 2023-24, real per student postsecondary education spending increased from $12,433 to $12,994 at an average annual rate of 1.5 per cent. This increase is largely due to a recovery in provincial spending on student financial assistance following reductions in higher federal supports introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, and higher consolidated spending by colleges, driven by growth in international student enrolment.

Figure 7.3 Average annual growth in real per student postsecondary education spending, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Years | 1990-91 to 1992-93 | 1992-93 to 1996-97 | 1996-97 to 1999-00 | 1999-00 to 2003-04 | 2003-04 to 2007-08 | 2007-08 to 2012-13 | 2012-13 to 2018-19 | 2018-19 to 2020-21 | 2020-21 to 2023-24 | 1990-91 to 2023-24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Annual Growth | 7.3 | -6.7 | 8.0 | -6.2 | 5.6 | -2.4 | 1.8 | -8.4 | 1.5 | -0.3 |

Select Service Levels

In this section, the FAO analyzes two broad service level trends in the postsecondary education sector: average tuition fees for domestic students and average student financial assistance payments. There are many other measures of postsecondary education sector service levels and performance. For more information, see Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario.

Tuition Fees for Domestic Students

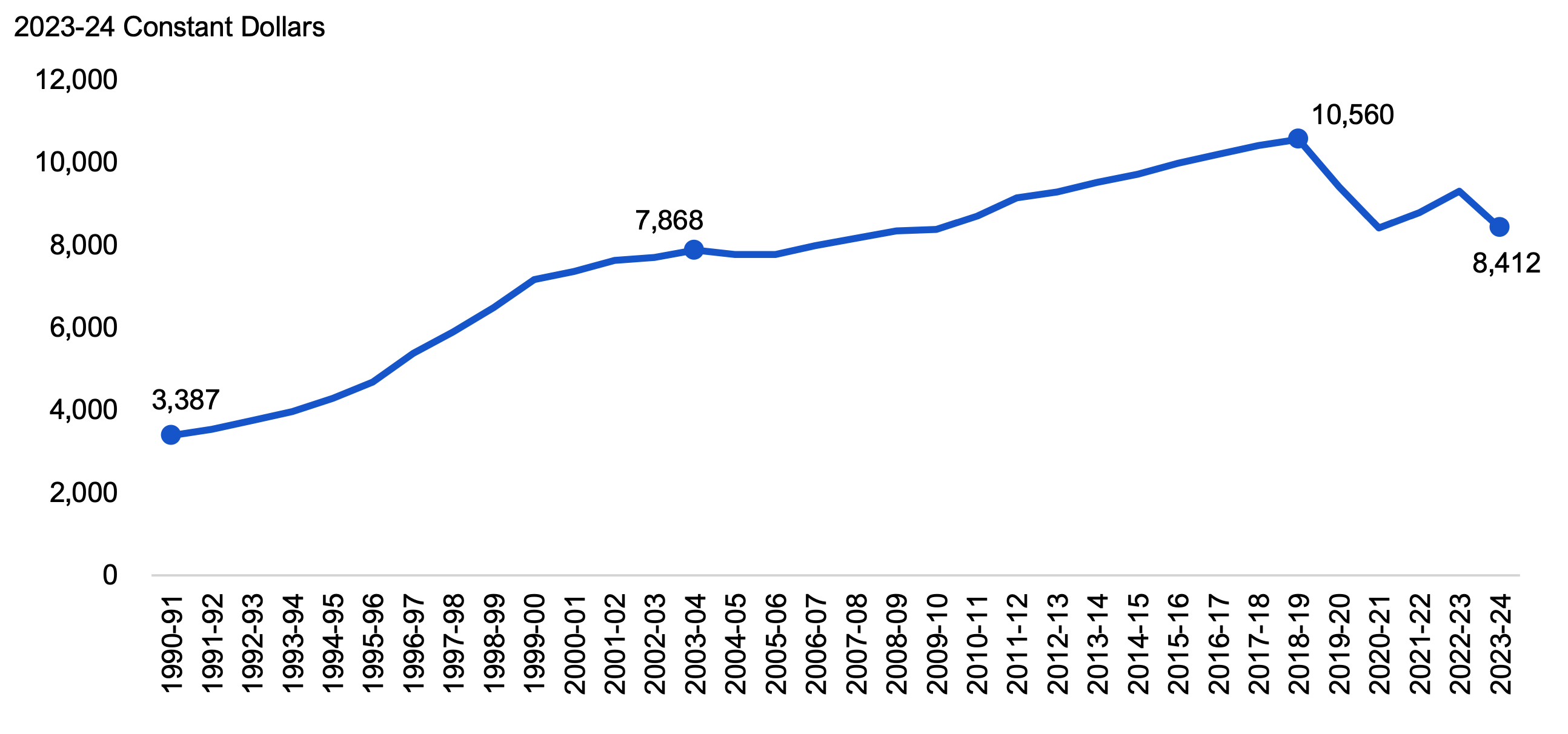

From 1990-91 to 2003-04, real average tuition fees for domestic students increased from $3,387 to $7,868, at an average annual rate of 6.7 per cent, as institutions increased tuition fees to offset reductions in government operating grants. From 2003-04 to 2018-19, annual growth in real average tuition fees slowed to 2.0 per cent and reached a peak of $10,560 in 2018-19. Real average tuition fees then declined to $8,412 in 2023-24, at an average annual rate of -4.4 per cent, following government policy to reduce tuition fees for domestic students by 10 per cent in 2019 and freeze tuition fees going forward.

Figure 7.4 Average tuition fees for domestic students in postsecondary education programs in Ontario, inflation-adjusted, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Note: Average tuition for both undergraduate and graduate students, weighted by enrolment.

Source: FAO analysis of Statistics Canada information

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Average Tuition Fee |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 3,387 |

| 1991-92 | 3,538 |

| 1992-93 | 3,743 |

| 1993-94 | 3,972 |

| 1994-95 | 4,285 |

| 1995-96 | 4,673 |

| 1996-97 | 5,384 |

| 1997-98 | 5,892 |

| 1998-99 | 6,488 |

| 1999-00 | 7,155 |

| 2000-01 | 7,364 |

| 2001-02 | 7,625 |

| 2002-03 | 7,698 |

| 2003-04 | 7,868 |

| 2004-05 | 7,766 |

| 2005-06 | 7,771 |

| 2006-07 | 7,976 |

| 2007-08 | 8,156 |

| 2008-09 | 8,337 |

| 2009-10 | 8,382 |

| 2010-11 | 8,705 |

| 2011-12 | 9,141 |

| 2012-13 | 9,290 |

| 2013-14 | 9,521 |

| 2014-15 | 9,715 |

| 2015-16 | 9,984 |

| 2016-17 | 10,198 |

| 2017-18 | 10,412 |

| 2018-19 | 10,560 |

| 2019-20 | 9,404 |

| 2020-21 | 8,418 |

| 2021-22 | 8,790 |

| 2022-23 | 9,312 |

| 2023-24 | 8,412 |

Student Financial Assistance Payments

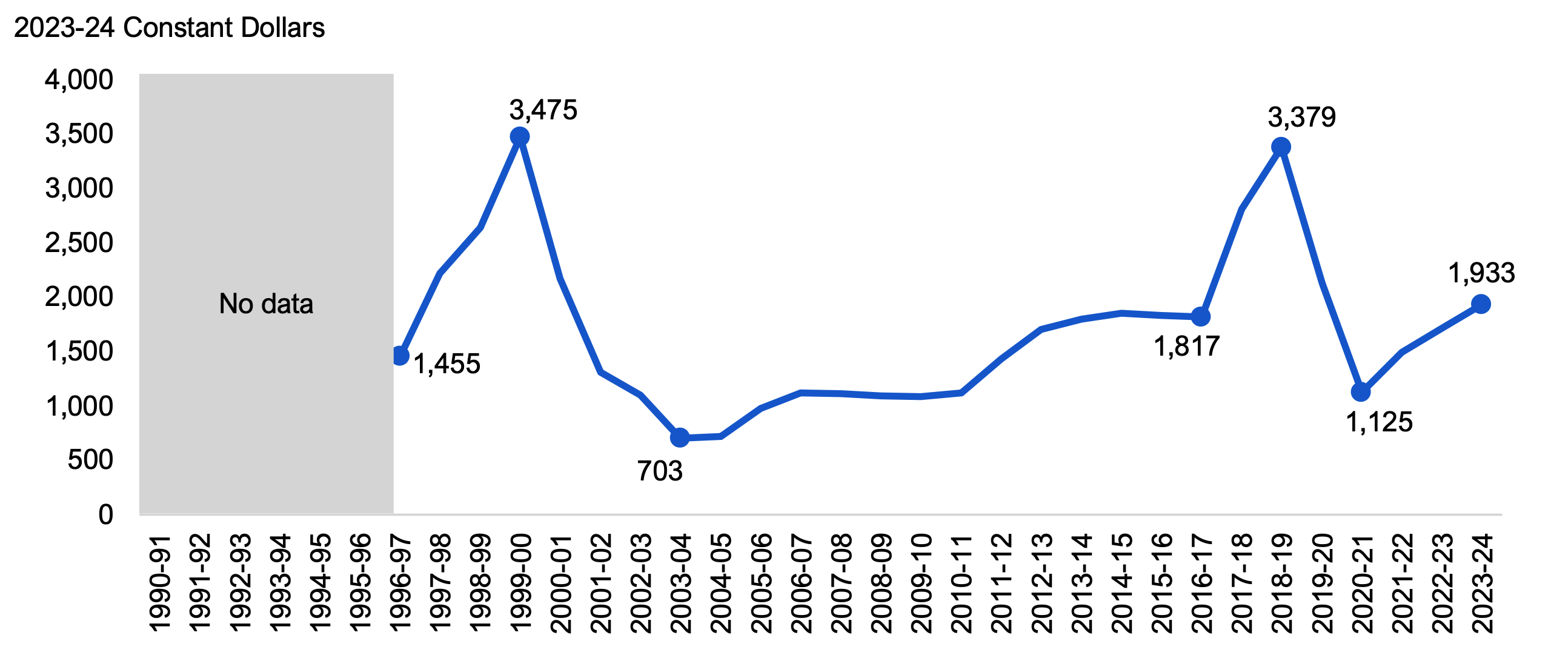

Between 1996-97 to 2003-04, real average annual student financial assistance payments[15] per domestic student reached a peak of $3,475 in 1999-00, then declined significantly to $703 per student by 2003-04. This decline was driven largely by the expansion of the federal government’s Canada Student Loans Program, which reduced provincial support, and a shift towards providing more support through loans over grants. Real average payments per domestic student then increased, reaching $1,817 in 2016-17, following enhancements made through the Reaching Higher Plan in 2005, and the introduction of a 30 per cent rebate on tuition for eligible students in 2012.

Real average annual student financial assistance payments per domestic student then increased further, reaching $3,379 per domestic student in 2018-19, following government policy to provide free tuition for eligible domestic students, which was provided through the Student Financial Assistance Program, a shift towards providing more support through grants over loans, and expansions to eligibility. Spending then declined to $1,125 in 2020-21 following the reversal and reform of these program enhancements in 2019. The decline in spending was also attributable to a 10 per cent reduction in tuition fees, which reduced the amount of tuition eligible for grants, and increased federal support for students during the COVID-19 pandemic, which offset provincial support. Since then, spending has increased to $1,933 per student in 2023-24, largely due to the reduction of federal supports related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 7.5 Student financial assistance payments per domestic student enrolled in postsecondary education, inflation-adjusted, 1996-97 to 2023-24

Note: Includes grants through the Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP), but excludes loans provided through OSAP

SourceStatistics Canada and FAO analysis of the Public Accounts of Ontario

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Payments Per Domestic Student |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | No Data |

| 1991-92 | No Data |

| 1992-93 | No Data |

| 1993-94 | No Data |

| 1994-95 | No Data |

| 1995-96 | No Data |

| 1996-97 | 1,455 |

| 1997-98 | 2,216 |

| 1998-99 | 2,640 |

| 1999-00 | 3,475 |

| 2000-01 | 2,173 |

| 2001-02 | 1,307 |

| 2002-03 | 1,097 |

| 2003-04 | 703 |

| 2004-05 | 716 |

| 2005-06 | 978 |

| 2006-07 | 1,121 |

| 2007-08 | 1,114 |

| 2008-09 | 1,090 |

| 2009-10 | 1,084 |

| 2010-11 | 1,120 |

| 2011-12 | 1,434 |

| 2012-13 | 1,706 |

| 2013-14 | 1,798 |

| 2014-15 | 1,852 |

| 2015-16 | 1,833 |

| 2016-17 | 1,817 |

| 2017-18 | 2,813 |

| 2018-19 | 3,379 |

| 2019-20 | 2,130 |

| 2020-21 | 1,125 |

| 2021-22 | 1,494 |

| 2022-23 | 1,715 |

| 2023-24 | 1,933 |

8. Children, Community and Social Services

Spending Trends

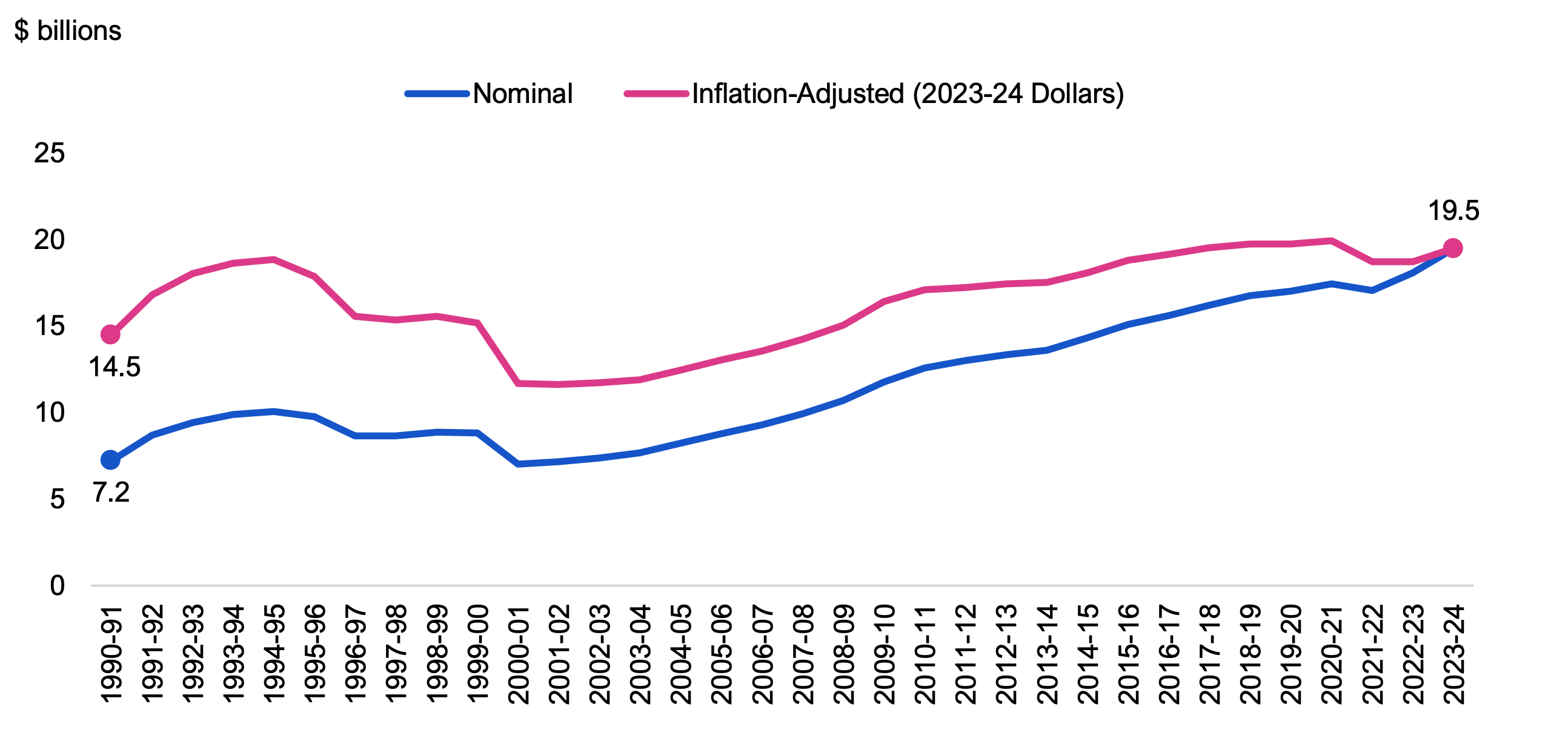

The children, community and social services sector is the fourth largest in the government, accounting for 9.4 per cent of total spending in 2023-24. This sector primarily consists of spending on financial and employment assistance to households in financial need, as well as targeted supports for adults, youth and children, victims of violence, and Indigenous peoples.[16] The FAO estimates children, community and social services sector spending grew at an average annual rate of 3.1 per cent from $7.2 billion in 1990-91 to $19.5 billion in 2023-24. After adjusting for inflation, this sector’s spending grew at an average annual rate of 0.9 per cent from 1990-91 to 2023-24.

Figure 8.1 Children, community and social services sector spending, nominal and inflation-adjusted, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Nominal | Inflation-Adjusted (2023-24 Dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 7.2 | 14.5 |

| 1991-92 | 8.7 | 16.8 |

| 1992-93 | 9.4 | 18.0 |

| 1993-94 | 9.9 | 18.6 |

| 1994-95 | 10.1 | 18.9 |

| 1995-96 | 9.8 | 17.9 |

| 1996-97 | 8.7 | 15.6 |

| 1997-98 | 8.6 | 15.3 |

| 1998-99 | 8.9 | 15.6 |

| 1999-00 | 8.8 | 15.2 |

| 2000-01 | 7.0 | 11.7 |

| 2001-02 | 7.2 | 11.6 |

| 2002-03 | 7.4 | 11.7 |

| 2003-04 | 7.7 | 11.9 |

| 2004-05 | 8.2 | 12.5 |

| 2005-06 | 8.8 | 13.1 |

| 2006-07 | 9.3 | 13.6 |

| 2007-08 | 9.9 | 14.2 |

| 2008-09 | 10.7 | 15.1 |

| 2009-10 | 11.8 | 16.4 |

| 2010-11 | 12.6 | 17.1 |

| 2011-12 | 13.0 | 17.2 |

| 2012-13 | 13.3 | 17.4 |

| 2013-14 | 13.6 | 17.6 |

| 2014-15 | 14.3 | 18.1 |

| 2015-16 | 15.1 | 18.8 |

| 2016-17 | 15.6 | 19.1 |

| 2017-18 | 16.2 | 19.5 |

| 2018-19 | 16.8 | 19.7 |

| 2019-20 | 17.0 | 19.7 |

| 2020-21 | 17.4 | 19.9 |

| 2021-22 | 17.1 | 18.7 |

| 2022-23 | 18.1 | 18.7 |

| 2023-24 | 19.5 | 19.5 |

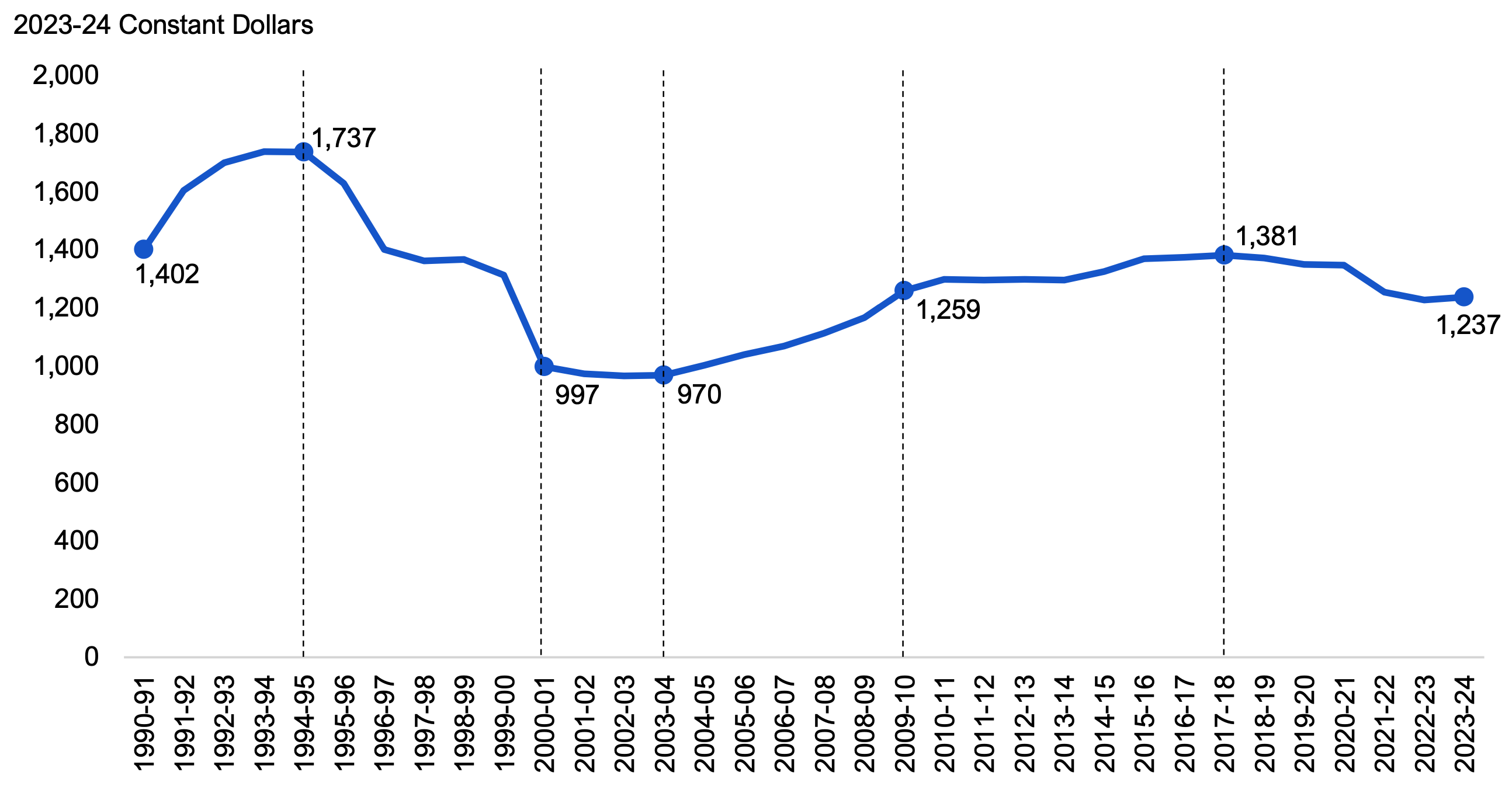

In addition to inflation, an important cost driver of children, community and social services sector spending is population growth. The following presents children, community and social services sector spending on an inflation-adjusted (i.e., real) per capita basis to provide a better indication of the impact that spending has on service levels over time. The FAO estimates real per capita children, community and social services sector spending decreased at an average annual rate of -0.4 per cent from $1,402 per person in 1990-91 to $1,237 per person in 2023-24.

Figure 8.2 Children, community and social services sector spending per capita, inflation-adjusted, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | Spending Per Capita |

|---|---|

| 1990-91 | 1,402 |

| 1991-92 | 1,604 |

| 1992-93 | 1,700 |

| 1993-94 | 1,737 |

| 1994-95 | 1,737 |

| 1995-96 | 1,627 |

| 1996-97 | 1,402 |

| 1997-98 | 1,362 |

| 1998-99 | 1,366 |

| 1999-00 | 1,314 |

| 2000-01 | 997 |

| 2001-02 | 973 |

| 2002-03 | 967 |

| 2003-04 | 970 |

| 2004-05 | 1,004 |

| 2005-06 | 1,040 |

| 2006-07 | 1,069 |

| 2007-08 | 1,112 |

| 2008-09 | 1,167 |

| 2009-10 | 1,259 |

| 2010-11 | 1,298 |

| 2011-12 | 1,296 |

| 2012-13 | 1,299 |

| 2013-14 | 1,296 |

| 2014-15 | 1,326 |

| 2015-16 | 1,369 |

| 2016-17 | 1,374 |

| 2017-18 | 1,381 |

| 2018-19 | 1,371 |

| 2019-20 | 1,350 |

| 2020-21 | 1,349 |

| 2021-22 | 1,255 |

| 2022-23 | 1,227 |

| 2023-24 | 1,237 |

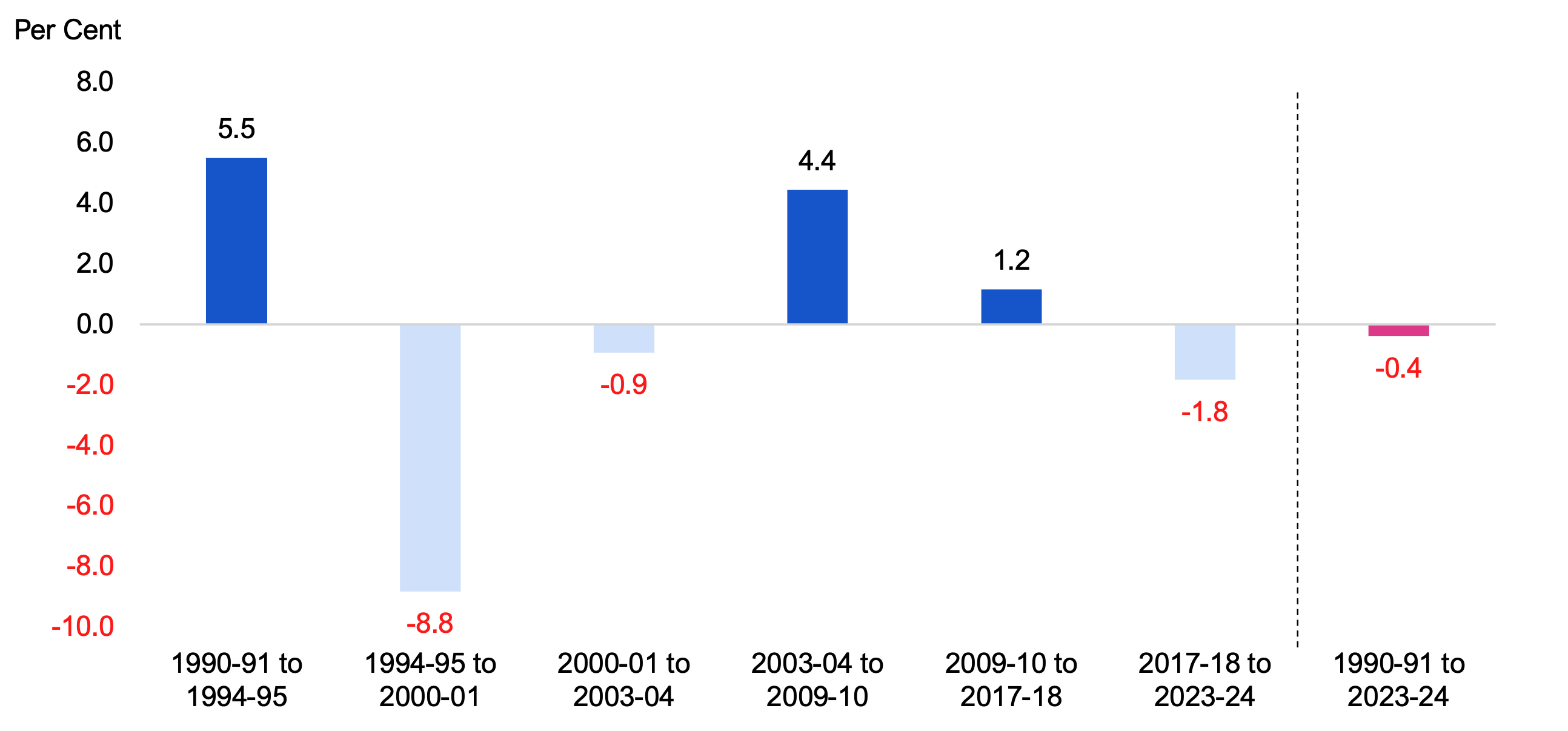

Based on real per capita spending, the FAO has identified six distinct periods of children, community and social services sector spending between 1990-91 to 2023-24:

1990-91 to 1994-95

From 1990-91 to 1994-95, real per capita children, community and social services spending increased from $1,402 to $1,737 at an average annual rate of 5.5 per cent. This growth was driven by government policy to increase social assistance benefit levels and rapid growth in the number of social assistance cases following the early 1990s recession (see the Select Service Levels section below for more information).

1994-95 to 2000-01

From 1994-95 to 2000-01, real per capita children, community and social services spending decreased from $1,737 to $997 at an average annual rate of -8.8 per cent. In 1995-96, the Province began to reform the social assistance system by cutting benefit rates and tightening the eligibility criteria for social assistance, which led to reductions in nominal spending. As part of the reform, General Welfare Assistance was replaced by Ontario Works (OW) and Family Benefits was replaced by the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP).

2000-01 to 2003-04

From 2000-01 to 2003-04, real per capita spending declined at an average annual rate of -0.9 per cent from $997 to $970. This decline was driven by lower spending on social assistance as the number of cases fell at an average annual rate of -0.9 per cent during this period, while ODSP and OW allowance rates remained unchanged. This reduction in spending was partially offset by increased spending on child welfare to address higher volumes of children in care.

2003-04 to 2009-10

From 2003-04 to 2009-10, real per capita spending grew from $970 to $1,259 at an average annual rate of 4.4 per cent. Growth was primarily driven by increases to ODSP and OW allowance rates, and increased funding to child protection agencies, women’s shelters, Children’s Treatment Centres, and the Healthy Babies, Healthy Children program and other early intervention services. Additionally, in 2007-08, the Province introduced the Ontario Child Benefit (OCB) and increased funding for Autism and the Developmental Services program for adults with developmental disabilities.

2009-10 to 2017-18

From 2009-10 to 2017-18, real per capita spending grew from $1,259 to $1,381 at an average annual rate of 1.2 per cent. Growth was primarily driven by increases to ODSP, OW and OCB allowance rates; the upload of the municipal share of social assistance program funding to the Province;[17] expansion of the Developmental Services program; and increased program funding in Children’s Treatment and Rehabilitation, Child Welfare and Autism.

2017-18 to 2023-24

From 2017-18 to 2023-24, real per capita spending fell from $1,381 to $1,237 at an average annual rate of ‑1.8 per cent. This reduction is largely due to declines in inflation-adjusted ODSP and OW allowance rates.[18] Additionally, ODSP and OW caseloads declined during the COVID-19 pandemic largely because federal income supports made some individuals ineligible for provincial social assistance. These declines were partially offset by investments in Developmental Services and the Autism program.

Figure 8.3 Average annual growth in real per capita children, community and social services spending, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Source: FAO calculations, Statistics Canada, Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Accessible version

| Fiscal Years | 1990-91 to 1994-95 | 1994-95 to 2000-01 | 2000-01 to 2003-04 | 2003-04 to 2009-10 | 2009-10 to 2017-18 | 2017-18 to 2023-24 | 1990-91 to 2023-24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Annual Growth | 5.5 | -8.8 | -0.9 | 4.4 | 1.2 | -1.8 | -0.4 |

Select Service Levels

In this section, the FAO analyzes two broad service level trends: the number of social assistance cases and average annual ODSP and OW allowances. There are many other measures of children, community and social services sector service levels and performance. For more information, see FAO, Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services: Spending Plan Review.

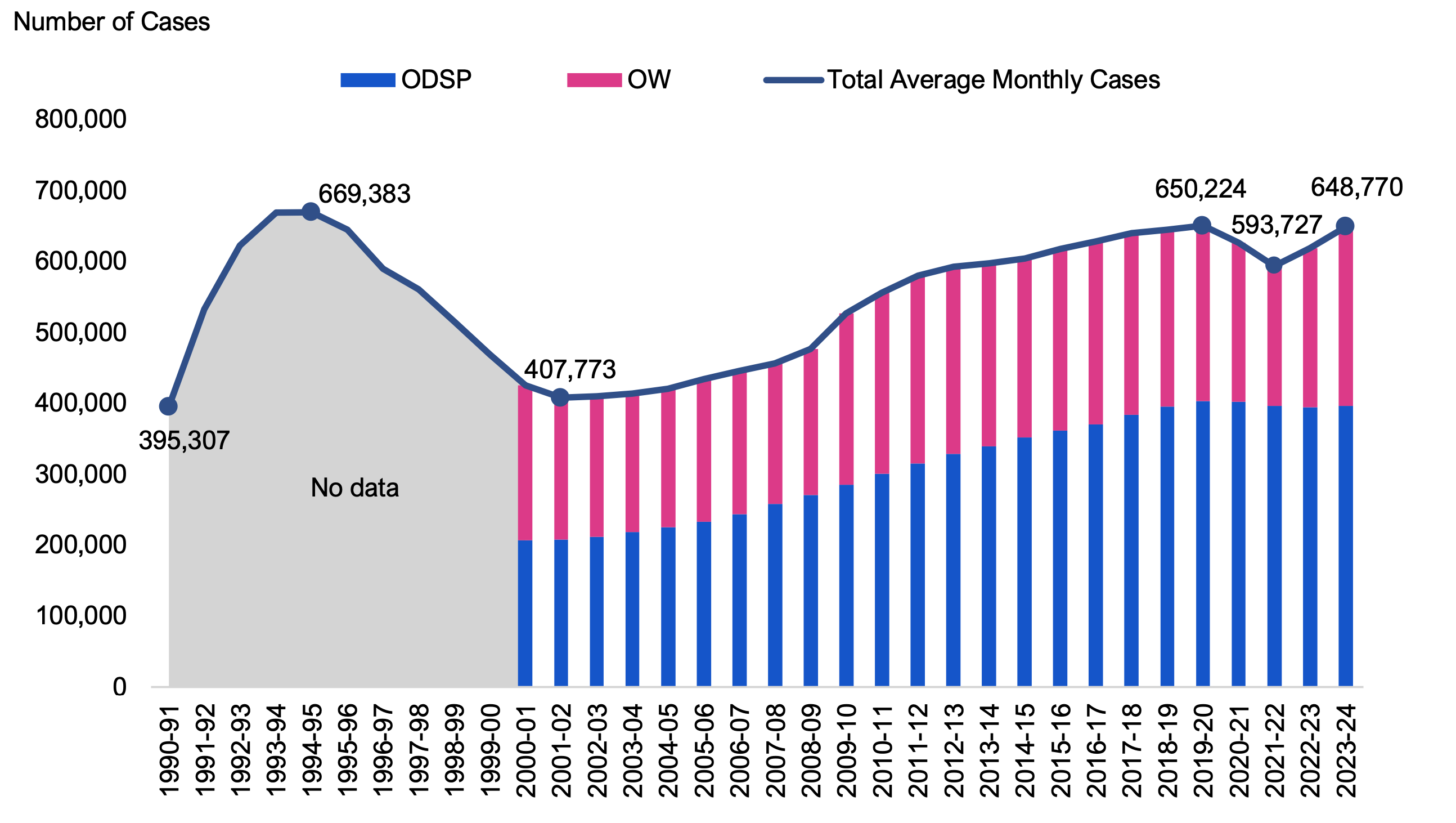

Social Assistance Cases

From 1990-91 to 1994-95, the average monthly number of social assistance cases grew at an average annual rate of 14.1 per cent following the early 1990s recession. After peaking in 1994-95, cases declined at an average annual rate of -6.8 per cent from 669,383 in 1994-95 to 407,773 in 2001-02 due to tightened eligibility criteria and strong job creation that caused the unemployment rate to decline. Total cases then grew at an average annual rate of 2.6 per cent from 407,773 in 2001-02 to 650,224 in 2019-20, driven by an average annual growth of 3.7 per cent and 1.2 per cent in ODSP and OW cases, respectively. Total cases declined from 2019-20 to 2021-22, falling from 650,224 to 593,727, largely because federal income supports made some recipients ineligible for social assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic. From 2021-22 to 2023-24, total cases increased, reaching 648,770 cases in 2023-24.

Figure 8.4 Average monthly number of social assistance cases, 1990-91 to 2023-24

Note: ODSP cases include Assistance for Children with Severe Disabilities cases. OW cases include Temporary Care Assistance cases

SourceGovernment of Ontario, Data Catalogue: Social Assistance Caseloads and FAO analysis of information provided by the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

Accessible version

| Fiscal Year | ODSP | OW | Total Average Monthly Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990-91 | No Data | No Data | 395,307 |

| 1991-92 | No Data | No Data | 532,792 |

| 1992-93 | No Data | No Data | 622,977 |

| 1993-94 | No Data | No Data | 669,322 |

| 1994-95 | No Data | No Data | 669,383 |

| 1995-96 | No Data | No Data | 645,163 |

| 1996-97 | No Data | No Data | 589,812 |

| 1997-98 | No Data | No Data | 560,747 |

| 1998-99 | No Data | No Data | 514,876 |

| 1999-00 | No Data | No Data | 468,957 |

| 2000-01 | 206,745 | 218,600 | 425,345 |

| 2001-02 | 208,070 | 199,703 | 407,773 |

| 2002-03 | 211,897 | 198,397 | 410,294 |

| 2003-04 | 218,888 | 195,331 | 414,219 |

| 2004-05 | 225,750 | 194,900 | 420,650 |

| 2005-06 | 232,859 | 201,650 | 434,510 |

| 2006-07 | 243,329 | 202,673 | 446,002 |

| 2007-08 | 257,828 | 198,697 | 456,525 |

| 2008-09 | 270,298 | 206,291 | 476,590 |

| 2009-10 | 285,292 | 241,910 | 527,202 |

| 2010-11 | 300,682 | 255,655 | 556,337 |

| 2011-12 | 314,795 | 265,380 | 580,175 |

| 2012-13 | 328,291 | 264,613 | 592,903 |

| 2013-14 | 339,795 | 257,698 | 597,493 |

| 2014-15 | 352,019 | 251,990 | 604,009 |

| 2015-16 | 361,562 | 256,009 | 617,571 |

| 2016-17 | 370,609 | 257,757 | 628,367 |

| 2017-18 | 383,428 | 256,164 | 639,593 |

| 2018-19 | 395,131 | 250,218 | 645,349 |

| 2019-20 | 403,069 | 247,155 | 650,224 |

| 2020-21 | 402,685 | 224,084 | 626,769 |

| 2021-22 | 396,763 | 196,964 | 593,727 |

| 2022-23 | 394,575 | 224,460 | 619,035 |

| 2023-24 | 396,848 | 251,922 | 648,770 |

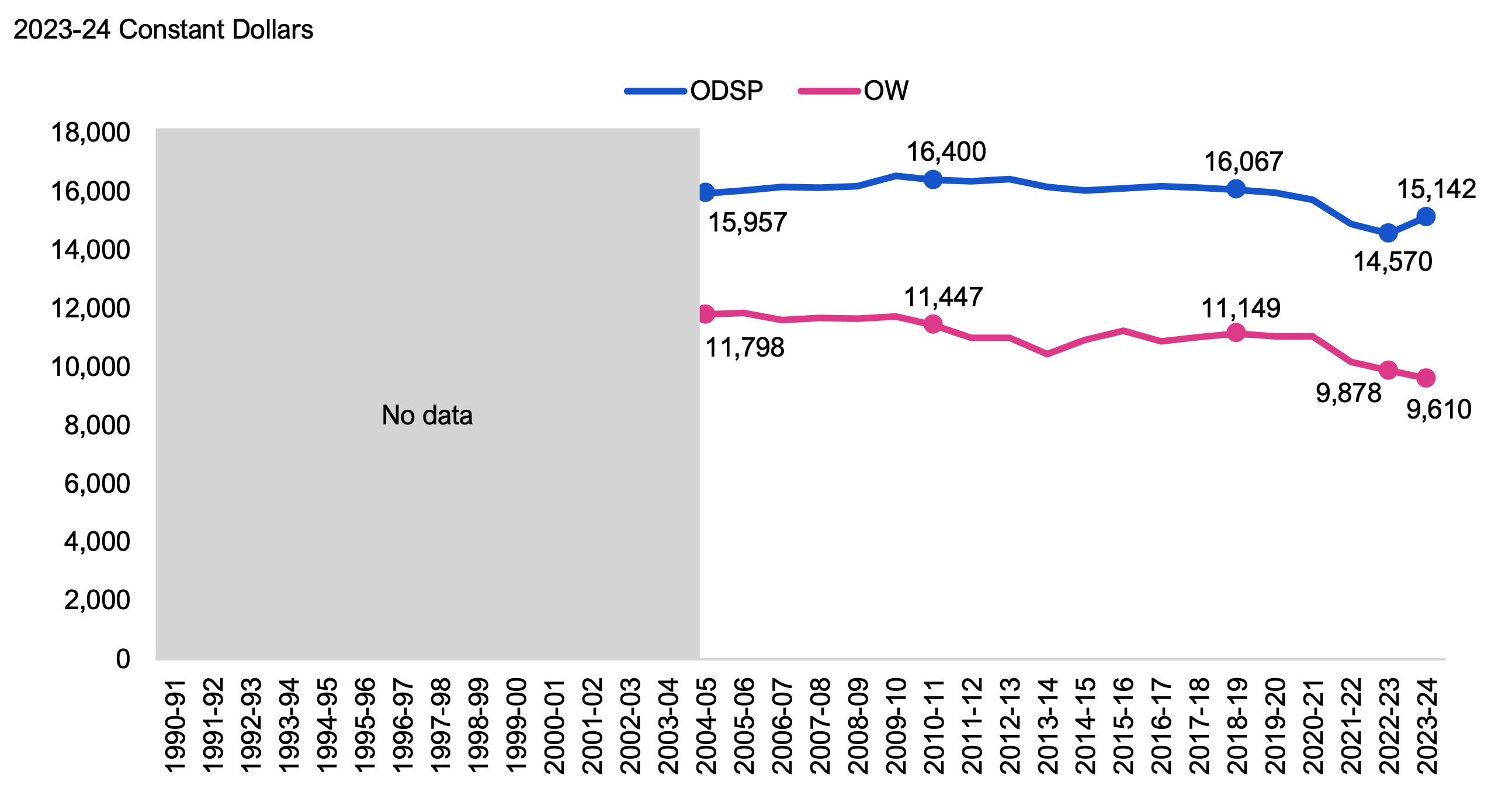

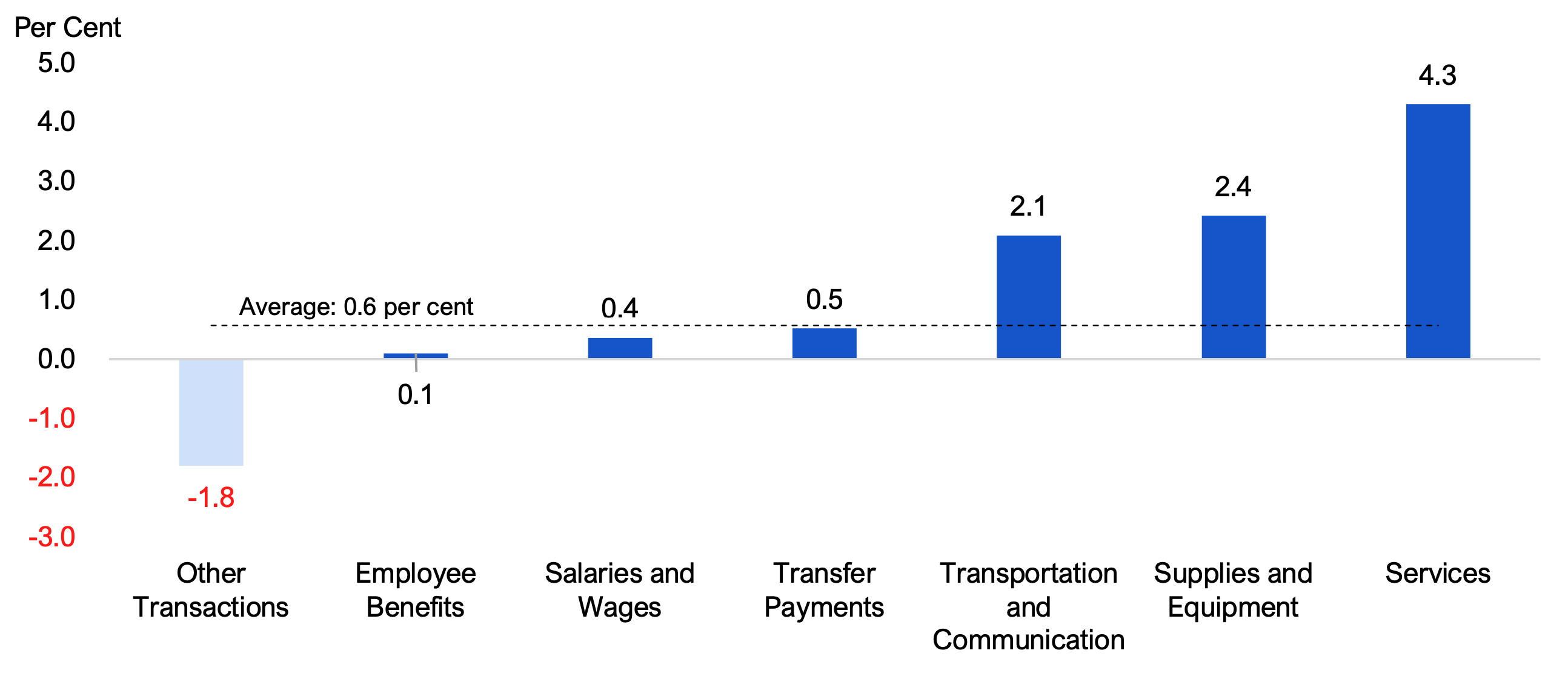

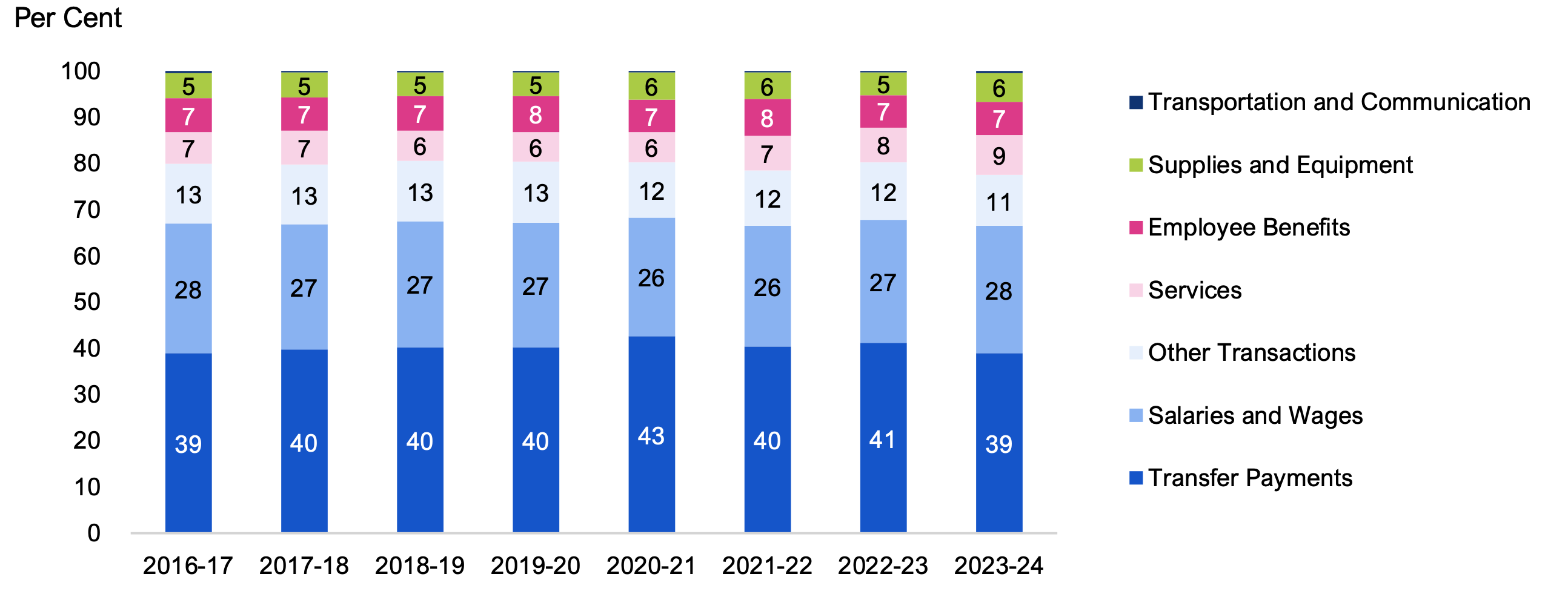

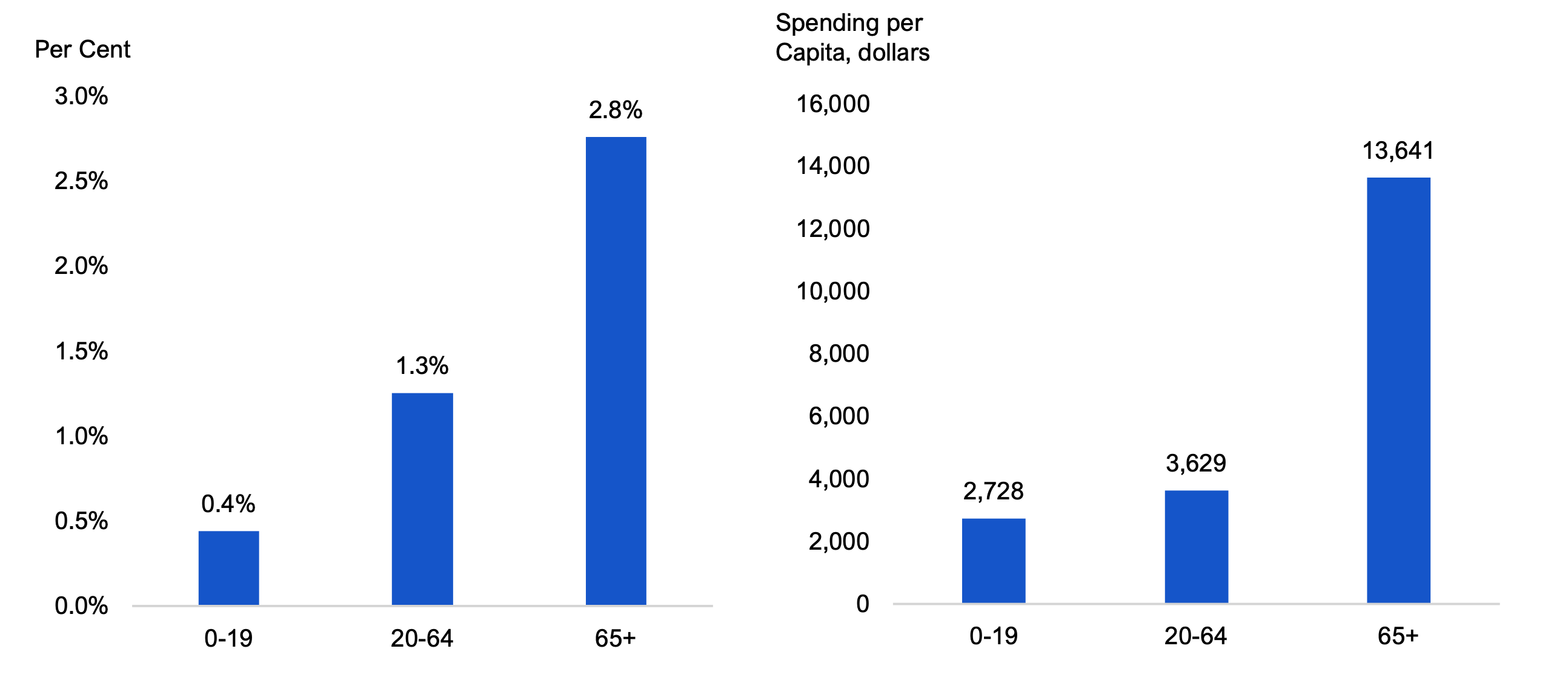

Average ODSP and OW Allowances