1. Summary

- This report reviews school buildings in Ontario, including building condition and the state of good repair. The report also compares student enrolment and school capacity to examine the number of schools that are under and over capacity. Finally, the report provides an estimate of the cost to maintain school buildings in a state of good repair and to address capacity pressures over the next 10 years, with a comparison of the FAO’s cost estimate to the amount of funding included in the Province’s 10-year capital plan in the 2024 Ontario Budget.

School Inventory

- In the 2023-24 school year, there were 4,850 schools[1] in 72 district school boards[2] in Ontario, which includes 3,953 elementary and 897 secondary schools. By school system, there were 3,033 schools in the English Public system, 1,331 schools in the English Catholic system, 167 schools in the French Public system, and 319 schools in the French Catholic system.

- French system schools are concentrated in Northern and Eastern Ontario, reflecting the distribution of French-speaking Ontarians. The Ottawa region had the highest share of Ontario’s French system schools at 31 per cent, followed by the Northeast region at 27 per cent and the Toronto region at 14 per cent.

- As of March 31, 2024, the FAO estimates that the total current replacement value (CRV)[3] of Ontario school buildings was $123.3 billion, which includes $80.9 billion for English Public system schools, $32.5 billion for English Catholic system schools, $3.0 billion for French Public system schools, and $6.9 billion for French Catholic system schools.

- Elementary schools had an average size of about 44,000 square feet and average CRV of $19.9 million, while secondary schools had an average size of about 121,000 square feet and average CRV of $49.9 million.

- Of the Province’s 72 school boards, the 10 largest school boards, ranked by total square footage of school buildings, accounted for 51 per cent of total school building square footage and 47 per cent of total school building CRV.

School Building Condition and State of Good Repair

- The condition of Ontario’s school buildings is assessed on a rolling five-year cycle, where independent engineers identify building components that need repair and replacement, and then quantify the cost to address these issues.

- Based on this information, and using methodologies developed by the Ministry of Infrastructure, the FAO estimates whether a school building is in a “state of good repair” or “below a state of good repair”, which means that the school building either requires rehabilitation (repairs) or should be replaced with a new school (rebuilt).

- As of March 31, 2024, the FAO estimates that 3,037 schools (62.6 per cent) were in a state of good repair (SOGR) and 1,813 schools (37.4 per cent) were below SOGR, of which 1,781 schools required rehabilitation and 32 schools should be replaced.

- By school system, 43.3 per cent of English Public system school buildings were below SOGR, 27.3 per cent of English Catholic school buildings were below SOGR, 31.7 per cent of French Public school buildings were below SOGR, and 25.7 per cent of French Catholic school buildings were below SOGR.

- The 10 largest school boards accounted for 52 per cent of all buildings below SOGR. Of the top 10 school boards, the Toronto District School Board (DSB) had the highest share of buildings below SOGR at 84.1 per cent, followed by the Thames Valley DSB at 52.5 per cent, and then the Toronto Catholic DSB at 45.6 per cent.

- Keeping assets in a state of good repair helps to maximize the benefits of public infrastructure and ensures assets are delivering their intended services in a condition that is considered acceptable from both an engineering and a cost management perspective.

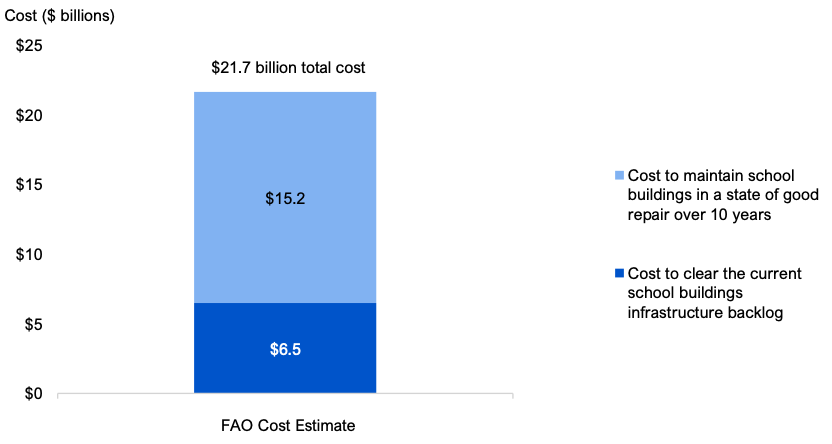

- The FAO estimates that the current cost to bring all school buildings into a state of good repair, also referred to in this report as the infrastructure backlog,[4] is $6.5 billion.

- Over the 10-year period, from 2024-25 to 2033-34, as school buildings continue to age and degrade, the FAO estimates that an additional $15.2 billion would need to be spent to maintain school buildings in a state of good repair.

- In total, the FAO estimates that it would cost $21.7 billion to clear the infrastructure backlog and maintain all school buildings in a state of good repair over the 2024-25 to 2033-34 period. This includes $16.3 billion for school buildings in the English Public school system, $4.0 billion for the English Catholic school system, $0.4 billion for the French Public school system, and $1.0 billion for the French Catholic school system.

School Capacity and Utilization

- In the 2023-24 school year, there were 2.0 million elementary and secondary students in Ontario schools and the total classroom capacity[5] was 2.3 million, which resulted in an average utilization rate of 87.6 per cent.

- Although the average school utilization rate was 87.6 per cent, utilization varied across schools. A total of 3,392 schools had utilization rates below 100 per cent, which included 858 schools with utilization rates below 60 per cent (also referred to as underutilized schools[6]) and 2,534 schools with utilization rates between 60 per cent and 100 per cent. In contrast, 1,458 schools had utilization rates over 100 per cent. Schools with utilization rates over 100 per cent are experiencing capacity pressures and are referred to as overcapacity.

- The English Catholic system had the highest proportion of overcapacity schools, with 35.2 per cent of schools operating above 100 per cent utilization, followed by the English Public system (29.7 per cent of schools), the French Public system (22.2 per cent of schools) and the French Catholic system (15.7 per cent of schools).

- The French Catholic system has the highest proportion of underutilized schools, at 42.3 per cent, followed by the French Public system (38.9 per cent of schools), the English Catholic system (16.2 per cent of schools) and the English Public system (14.6 per cent of schools).

- Of the 10 largest school boards, the Durham DSB had the highest proportion of overcapacity schools, with 69.2 per cent of schools operating above 100 per cent utilization, followed by the Thames Valley DSB (40.6 per cent of schools), the Waterloo Region DSB (39.0 per cent of schools), the York Region DSB (38.0 per cent of schools) and the Ottawa-Carleton DSB (35.4 per cent of schools).

- In terms of underutilization, of the 10 largest school boards, the Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB had the highest proportion of schools operating at less than 60 per cent capacity, with 27.8 per cent of schools underutilized, followed by the Toronto Catholic DSB (23.0 per cent of schools), the Toronto DSB (18.7 per cent of schools), the Ottawa-Carleton DSB (12.9 per cent of schools) and the Peel DSB (12.7 per cent of schools).

- Across the 1,458 schools that were overcapacity in the 2023-24 school year, there were 150,881 more students than spaces. Of this amount, the FAO estimates that 112,274 students were accommodated through 4,893 portables and 38,607 students were accommodated through other means, such as larger class sizes or teachers holding classrooms in non-classroom spaces.

- Across the 3,392 schools that were undercapacity (utilization less than 100 per cent) in the 2023-24 school year, there were 440,930 more spaces than students. Of this amount, there were 198,481 available spaces at 858 underutilized schools (utilization rates below 60 per cent) and 242,449 available spaces at 2,534 schools with utilization rates above 60 per cent but below 100 per cent.

Cost to Address Capacity Pressures

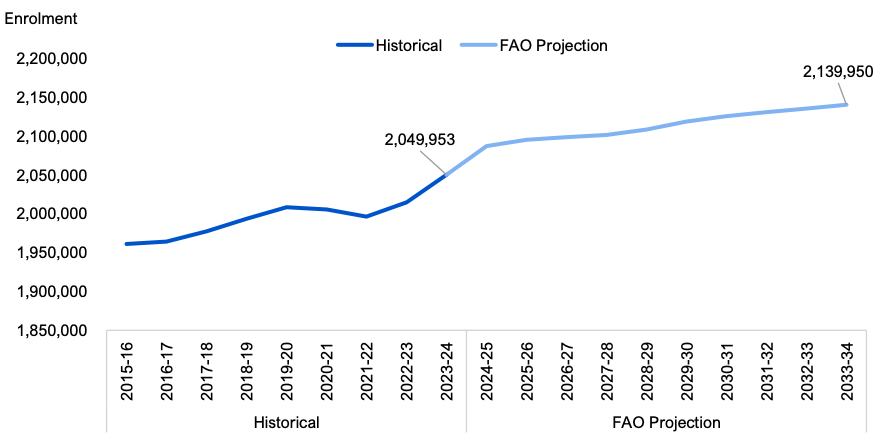

- The FAO estimates that school enrolment will increase by 89,996 students over the 10-year period to 2033-34, from 2.05 million in 2023-24 to 2.14 million in 2033-34, representing an average annual growth rate of 0.4 per cent. When combined with the 150,881 overcapacity students (as of the 2023-24 school year), the FAO estimates that school boards will be required to address total capacity pressures of 240,878 students in 2033-34.

- To address capacity pressures, after accounting for projected enrolment growth in undercapacity schools, school boards can change school boundary areas, use portables for temporary capacity pressures, or build new schools to meet permanent capacity pressures. The FAO estimates that, after accounting for the first three factors, 172,187 student spaces will need to be built by 2033-34 to address permanent capacity pressures.

- The FAO estimates that to create 172,187 new school spaces, the Province would need to build the equivalent of 227 new schools at a cost of $9.8 billion over 10 years. This includes $6.2 billion for the English Public system, $3.2 billion for the English Catholic system, $113 million for the French Public system, and $219 million for the French Catholic system.

- Of the 10 largest school boards, the Durham DSB has the highest 10-year cost at $880 million, followed by the York Region DSB ($553 million), the Ottawa-Carleton DSB ($494 million), the Thames Valley DSB ($490 million), the Halton DSB ($464 million) and the Waterloo Region DSB ($445 million).

Analysis of the Province’s School Board Capital Plan

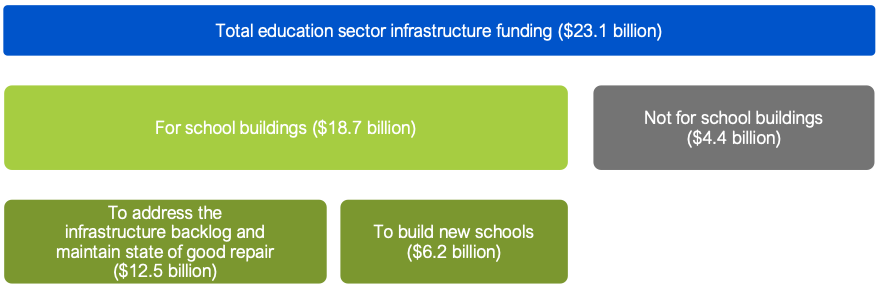

- The Province’s 10-year capital plan, as outlined in the 2024 Ontario Budget, allocates a total of $23.1 billion to the education sector for infrastructure investments from 2024-25 to 2033-34. Of this amount, the FAO estimates that $18.7 billion is specifically designated for capital investments in school buildings, of which $12.5 billion will be available for condition improvement and $6.2 billion for capacity expansion.

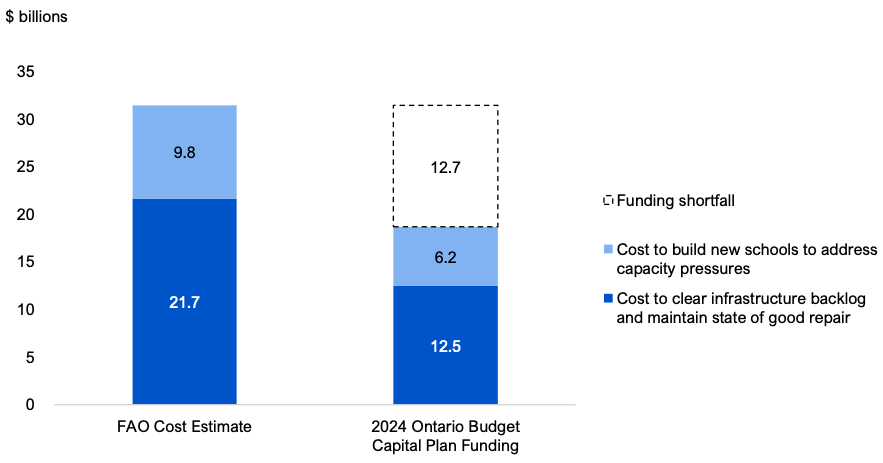

- As noted above, the FAO estimates that, over the next 10 years, it will cost a total of $21.7 billion to clear the school building infrastructure backlog and maintain schools in a state of good repair, and $9.8 billion to build new schools to address permanent capacity pressures, for a total combined cost of $31.4 billion over 10 years.

- Compared to the $18.7 billion over 10 years available for school buildings in the 2024 budget, this represents an estimated funding shortfall of $12.7 billion over 10 years.

- Infrastructure Backlog and State of Good Repair: The FAO estimates that it would cost $21.7 billion to clear the infrastructure backlog and keep school buildings in a state of good repair over the next 10 years. In contrast, the 2024 budget has allocated $12.5 billion over 10 years. If funded at this level, the FAO estimates that after 10 years, the percentage of school buildings that are not in a state of good repair would increase from 37.4 per cent in 2023-24 to 74.6 per cent in 2033-34. By 2033-34, the infrastructure backlog would grow from $6.5 billion to $22.1 billion.

- Addressing Capacity Pressures: The FAO estimates that 172,187 student spaces will need to be built by 2033-34 to address permanent capacity pressures, at a cost of $9.8 billion. In contrast, the 2024 budget has allocated $6.2 billion, which the FAO estimates is sufficient to create 109,946 new student spaces by 2033-34. This would result in an estimated 68,299 more students than permanent school spaces in 2033-34, a decrease of 54.7 per cent from the 150,881 overcapacity students in the 2023-24 school year. The estimated 68,299 overcapacity students in 2033-34 could be accommodated by using 2,901 portables, which is a decrease of 1,992 portables (40.7 per cent) from the 4,893 portables used to address capacity pressures in 2023-24.

Additional Information

- Additional information for each school board is available on the FAO’s website at: https://fao-on.org/school-boards-capital-2024-data.

2. Introduction

In the 2023-24 school year, there were approximately two million students across 4,850 elementary and secondary schools in 72 district school boards[7] under four school systems. The education system is overseen by the Ontario Ministry of Education, which sets curriculum standards, establishes policies and provides the majority of the funding.

Purpose and Structure

At the request of a Member of Provincial Parliament, this report reviews school buildings in Ontario, including school building condition and the cost to maintain schools in a state of good repair. The report also compares student enrolment and school capacity to examine the number of schools that are under and over capacity. Finally, the report provides an estimate of the cost to maintain school buildings in a state of good repair and to address capacity pressures over the next 10 years, with a comparison of the FAO’s cost estimate to the amount of funding included in the Province’s 10-year capital plan in the 2024 Ontario Budget.

The report is divided into the following chapters:

- Chapter 3 provides an overview of the school building inventory, including the number, size and value of publicly funded schools.

- Chapter 4 reviews the condition of these school buildings and estimates the cost to bring these assets into a state of good repair (i.e., the infrastructure backlog) and to maintain buildings in a state of good repair over the next 10 years.

- Chapter 5 reviews school capacity and utilization as of the 2023-24 school year.

- Chapter 6 estimates the cost to expand school spaces to accommodate current capacity pressures and projected enrolment growth over the next 10 years.

- Chapter 7 compares the FAO’s total estimated cost to maintain schools in a state of good repair and address capacity pressures to the amount of funding included in the Province’s 10-year capital plan.

Scope and Methodology

This report focuses on school buildings owned by the Province’s 72 school boards[8] that are actively serving enrolled students and excludes buildings held for disposal and office/administration buildings. The report also excludes other asset classes, such as land, equipment and information technology. In cases where multiple schools are located in one building, the FAO reports numbers on a school basis (i.e., two different capacity values but same building condition). Finally, the report analyzes the infrastructure funding requirements to maintain a state of good repair and expand school capacity to meet enrolment pressures; the report excludes the operational costs of schools and expenses for the day-to-day maintenance of buildings.

Data for this report were sourced from publicly available information and data provided by the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Infrastructure and Treasury Board Secretariat. Projections were calculated using FAO models, incorporating both historical trends and future forecasts. All values are in nominal dollars. More details on the FAO’s methodology are available upon request.

Additional Information

For additional information by school board, please visit the FAO’s website at: https://fao-on.org/school-boards-capital-2024-data.

3. School Inventory

In the 2023-24 school year, there were 4,850 schools[9] in Ontario, which includes 3,953 elementary and 897 secondary schools. Three economic regions[10] account for over 60 per cent of all schools, with about 1,800 schools in the Toronto region, 610 schools in the Hamilton – Niagara Peninsula region and 550 schools in the Ottawa region.

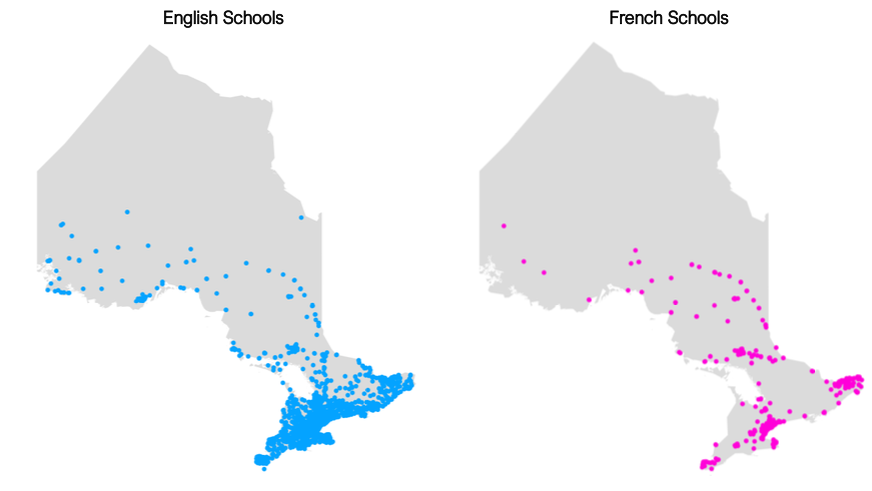

By system, there were 4,364 schools in the English Public and English Catholic systems, and 486 schools in the French Public and French Catholic systems. English schools are concentrated in Southern and Western Ontario, with 39 per cent of English schools located in the Toronto region, followed by 13 per cent in the Hamilton – Niagara Peninsula region and 10 per cent in the Kitchener – Waterloo – Barrie region.

By comparison, the French systems have a higher distribution of schools in Northern and Eastern Ontario compared to English systems, reflecting the distribution of French-speaking Ontarians. The Ottawa region had the highest share of Ontario’s French schools at 31 per cent, followed by the Northeast region at 27 per cent and the Toronto region at 14 per cent.

Figure 3.1Location of English and French schools in Ontario as of the 2023-24 school year

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Value of School Buildings

The current replacement value (CRV) of infrastructure is a measurement for infrastructure planning purposes, and an important metric relating to the cost of building and maintaining schools. CRV refers to the estimated cost of rebuilding an asset with the equivalent capacity, functionality and performance as the original asset, based in today’s dollars.[11] In this report, the CRV is based on Ministry of Education funding benchmarks, which include the cost of a structure (roofs, walls and windows), interior (doors, carpets and flooring), mechanical services (HVAC, electrical and plumbing) and other items (lighting).[12]

Overall, the FAO estimates the total CRV of Ontario school buildings at $123.3 billion as of March 31, 2024.[13] The average CRV for each school is estimated at $25.4 million. Elementary schools had an average size of about 44,000 square feet and average CRV of $19.9 million, while secondary schools had an average size of about 121,000 square feet and average CRV of $49.9 million.

Value by Square Foot

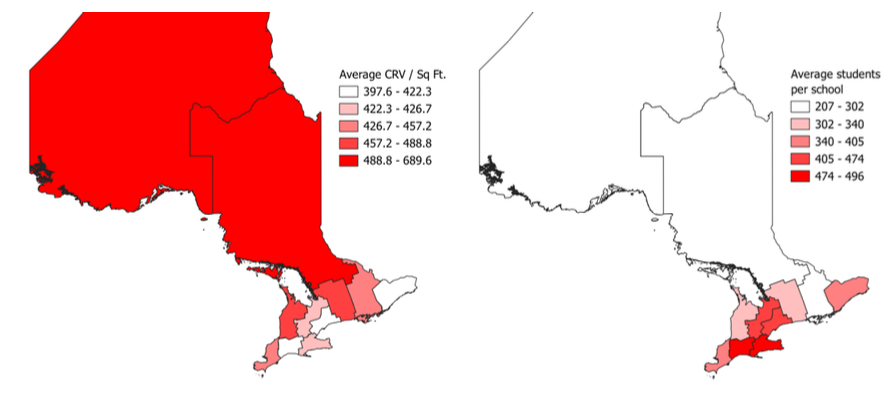

The FAO estimates the average CRV per square foot at $439 in 2024. Over the last 15 years, the FAO estimates that the average cost per square foot has increased by 4.8 per cent per year, due in part to the modernization of school buildings, such as improved ventilation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The FAO’s CRV estimates in this report include this impact and assume that all school buildings have a value consistent with the design scope and standards of 2024.

By region, school buildings located in Northern Ontario have a higher average CRV per square foot. The Northeast and Northwest regions have an estimated average CRV per square foot of about $613 compared to the Toronto region, which has the lowest cost per square foot at about $407.

This regional difference can be partially attributed to economies of scale. Construction costs per square foot tend to be higher for smaller schools, which are more common in Northern Ontario. For example, small schools (with enrolment under 110) have an average CRV per square foot of $576, compared to the Ontario-wide average of $439 per square foot for an average enrolment of 423 students. Small schools accounted for 32.4 per cent of all schools in Northern Ontario, but only 4.5 per cent in the Toronto region.

Figure 3.2FAO estimate of CRV per square foot (2024 dollars) and students per school (2023-24 school year), by region

Note: CRV refers to current replacement value.

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

School Inventory by School System and School Board

The total current replacement value (CRV) of Ontario’s school buildings at $123.3 billion includes $80.9 billion for over 3,000 schools in the English Public school system, $32.5 billion for over 1,300 schools in the English Catholic system, $3.0 billion for over 160 schools in the French Public system and $6.9 billion for over 300 schools in the French Catholic system. The FAO estimates that the French Catholic system has the highest construction costs per square foot at $515, followed by the French Public system at $473, the English Catholic system at $449 and the English Public system at $429.

French schools are typically smaller, which makes them more expensive per square foot to build. French Catholic schools average 41,900 square feet and French Public schools average 38,400 square feet. In contrast, English schools are larger, which lowers their cost per square foot due to economies of scale. English Catholic schools average 54,400 square feet and English Public schools average 62,100 square feet.

| School System | Total Number of Schools |

Total Square Footage (millions) |

Total School CRV ($ billions) |

Average CRV per sq. ft. ($) |

Average CRV per school ($ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English Public | 3,033 | 188.4 | 80.9 | 429 | 26.7 |

| English Catholic | 1,331 | 72.5 | 32.5 | 449 | 24.4 |

| French Public | 167 | 6.4 | 3.0 | 473 | 18.2 |

| French Catholic | 319 | 13.4 | 6.9 | 515 | 21.6 |

| Total | 4,850 | 280.6 | 123.3 | 439 | 25.4 |

The 10 largest school boards, ranked by total square footage of school buildings, accounted for 51 per cent of total school building square footage. The largest board was the Toronto District School Board (DSB), which had 578 schools totalling over 41 million square feet, followed by the Peel DSB at 260 schools and over 19 million square feet, and then the York Region DSB at 213 schools and almost 16 million square feet. In terms of CRV, the top 10 school boards accounted for 47 per cent of the total at $58.4 billion. More information on individual school boards is available at https://fao-on.org/school-boards-capital-2024-data.

| School Board | Total Number of Schools |

Total Square Footage (millions) |

Total School CRV ($ millions) |

Average CRV per sq. ft. ($) |

Average CRV per school ($ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto DSB | 578 | 41.2 | 15,790 | 384 | 27.3 |

| Peel DSB | 260 | 19.4 | 8,237 | 425 | 31.7 |

| York Region DSB | 213 | 15.9 | 6,263 | 394 | 29.4 |

| Toronto Catholic DSB | 204 | 11.5 | 5,128 | 446 | 25.1 |

| Thames Valley DSB | 160 | 10.5 | 4,430 | 421 | 27.7 |

| Ottawa-Carleton DSB | 147 | 10.4 | 4,182 | 402 | 28.5 |

| Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB | 151 | 10.1 | 4,304 | 424 | 28.5 |

| Durham DSB | 130 | 9.0 | 3,614 | 402 | 27.8 |

| Waterloo Region DSB | 123 | 7.8 | 3,198 | 410 | 26.0 |

| Halton DSB | 110 | 7.4 | 3,260 | 438 | 29.6 |

| All other school boards | 2,774 | 137.3 | 64,878 | 472 | 23.4 |

| Total | 4,850 | 280.6 | 123,284 | 439 | 25.4 |

4. School Building Condition and State of Good Repair

The state of public infrastructure is typically measured by condition indices, which are based on engineering assessments of individual assets. Ontario’s school buildings are assessed on a rolling five-year cycle through the School Facility Condition Assessment Program [14]. Through this program, independent engineers identify building components that need repair and replacement, and then quantify the cost to address these issues. The cost of these identified needs is then divided by the building’s current replacement value (CRV) to develop a Facility Condition Index (FCI) [15].

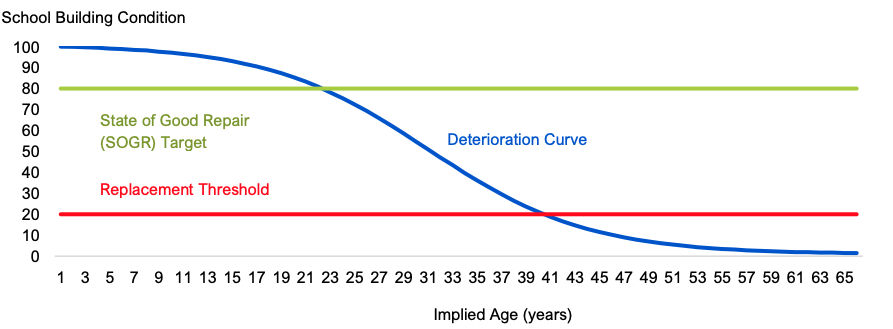

In this report, the FAO standardizes these measurements, so that 100 indicates the highest condition asset and zero indicates the lowest condition. Based on assumptions developed by the Ministry of Infrastructure, a building with a condition index at or above 80 is considered to be in a “state of good repair”, a building with a condition index below 80 and at or above 20 should be rehabilitated,[16] and a building with a condition index below 20 should be replaced[17] with a new asset (i.e., rebuilt).

As buildings age, their state of repair declines. Eventually, buildings fall out of a state of good repair (SOGR), at which point capital rehabilitation projects would be undertaken. As the condition deteriorates further, the building reaches a point where replacement of the asset is considered more cost effective.

Figure 4.1How a school building’s condition deteriorates over time

Note: The FAO defines school building condition based on the Facility Condition Index (FCI), where 100 represents the highest condition and 0 the lowest.

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

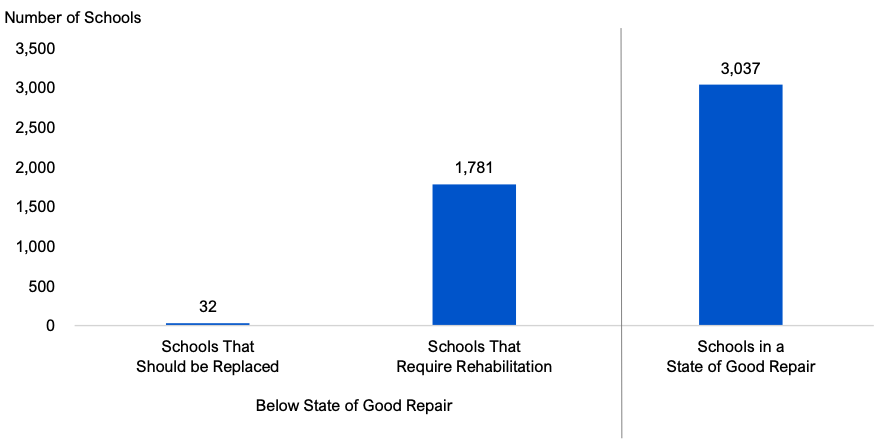

As of March 31, 2024, 3,037 schools (62.6 per cent) were at or above the target for state of good repair, with a condition at or above 80. On the other hand, 1,813 schools (37.4 per cent) were below the state of good repair target,[18] of which 1,781 schools required rehabilitation and 32 schools were below the replacement threshold, indicating that these schools should be replaced.

Figure 4.2FAO estimate of the number of schools by condition rating as of March 31, 2024

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Cost to Address the Infrastructure Backlog and Maintain a State of Good Repair

Keeping assets in a state of good repair helps to maximize the benefits of public infrastructure and ensures assets are delivering their intended services in a condition that is considered acceptable from both an engineering and a cost management perspective. The cost required to bring assets into a state of good repair is defined in this report as the infrastructure backlog.[19]

The FAO estimates that the cost to bring all school buildings into a state of good repair and clear the infrastructure backlog is $6.5 billion. The infrastructure backlog is comprised of:

- $5.5 billion to rehabilitate 1,781 schools that are not in a state of good repair; and

- $1.0 billion to replace 32 schools that are not in a state of good repair and have reached a point where replacement of the asset is more cost-effective than rehabilitation.

Over the 10-year period from 2024-25 to 2033-34, as school buildings continue to age and degrade, the FAO estimates that the Province would need to spend an additional $15.2 billion to maintain school buildings in a state of good repair. In total, the FAO estimates that it would cost $21.7 billion to bring all school buildings to a state of good repair and maintain them in good condition over the 2024-25 to 2033-34 period.

Figure 4.3FAO estimate of the cost to clear the infrastructure backlog and keep all school buildings in a state of good repair, 2024-25 to 2033-34, $ billions

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Cost by School System and School Board

By school system, the FAO estimates a total cost of $16.3 billion over 10 years to reach and maintain a state of good repair for school buildings in the English Public school system, including $5.3 billion to clear the infrastructure backlog and $11.0 billion to maintain a state of good repair. For the English Catholic school system, the estimate is $4.0 billion, of which $0.8 billion is required to clear the infrastructure backlog and $3.1 billion is required to maintain a state of good repair. The FAO estimates a total cost of $0.4 billion for the French Public school system ($0.1 billion for the infrastructure backlog and $0.3 billion to maintain a state of good repair) and $1.0 billion for the French Catholic school system ($0.3 billion for the infrastructure backlog and $0.8 billion to maintain a state of good repair).

As a share of CRV, the total cost to reach and maintain a state of good repair is highest for the English Public school system (20.1 per cent), implying that assets in this school system are in worse condition compared to the other systems. This is because the English Public system had the highest share of buildings below a state of good repair at 43.3 per cent. The French Catholic system had the next highest cost as a share of CRV at 15.1 per cent, followed by the English Catholic system at 12.2 per cent, and then the French Public system at 12.1 per cent.

| School System | Number of Buildings Below SOGR |

Share of Buildings Below SOGR (%) |

Infrastructure Backlog as of March 31, 2024 ($ millions) |

Additional Cost to Maintain SOGR ($ millions) |

Total 10-Year Cost ($ millions) |

Total Cost to CRV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English Public | 1,314 | 43.3 | 5,302 | 10,982 | 16,284 | 20.1 |

| English Catholic | 364 | 27.3 | 831 | 3,131 | 3,962 | 12.2 |

| French Public | 53 | 31.7 | 99 | 270 | 369 | 12.1 |

| French Catholic | 82 | 25.7 | 270 | 772 | 1,042 | 15.1 |

| Total | 1,813 | 37.4 | 6,502 | 15,155 | 21,657 | 17.6 |

The 10 largest school boards by school building square footage accounted for 52 per cent of all buildings below a state of good repair. Of the top 10 school boards, the Toronto DSB had the highest share of buildings below a state of good repair at 84.1 per cent, followed by the Thames Valley DSB at 52.5 per cent, and then the Toronto Catholic DSB at 45.6 per cent. The FAO estimates that the total cost to reach and maintain a state of good repair is highest for the Toronto DSB, at $6.8 billion, or 42.8 per cent of CRV. More information on individual school boards is available at: https://fao-on.org/school-boards-capital-2024-data.

| School Board | Number of Buildings Below SOGR |

Share of Buildings Below SOGR (%) |

Infrastructure Backlog as of March 31, 2024 ($ millions) |

Additional Cost to Maintain SOGR ($ millions) |

Total 10- Year Cost ($ millions) |

Total Cost to CRV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto DSB | 486 | 84.1 | 2,863 | 3,902 | 6,765 | 42.8 |

| Peel DSB | 65 | 25.0 | 259 | 765 | 1,023 | 12.4 |

| York Region DSB | 24 | 11.3 | 33 | 309 | 342 | 5.5 |

| Toronto Catholic DSB | 93 | 45.6 | 246 | 704 | 950 | 18.5 |

| Thames Valley DSB | 84 | 52.5 | 353 | 565 | 918 | 20.7 |

| Ottawa-Carleton DSB | 45 | 30.6 | 127 | 433 | 561 | 13.4 |

| Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB | 36 | 23.8 | 77 | 339 | 416 | 9.7 |

| Durham DSB | 32 | 24.6 | 76 | 313 | 389 | 10.8 |

| Waterloo Region DSB | 55 | 44.7 | 178 | 401 | 579 | 18.1 |

| Halton DSB | 19 | 17.3 | 48 | 218 | 267 | 8.2 |

| All other school boards | 874 | 31.5 | 2,241 | 7,205 | 9,447 | 14.6 |

| Total | 1,813 | 37.4 | 6,502 | 15,155 | 21,657 | 17.6 |

5. School Capacity and Utilization

In the 2023-24 school year, there were 2.0 million elementary and secondary students in Ontario schools and the total classroom capacity[20] was 2.3 million, which resulted in an average utilization rate of 87.6 per cent. By system, English Catholic schools had an average utilization rate of 90.9 per cent, followed by English Public schools at 88.0 per cent, French Public schools at 72.4 per cent and French Catholic schools at 69.3 per cent.

| School System | Number of Enrolled Students | Capacity (students) | Utilization Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| English Public | 1,367,485 | 1,553,485 | 88.0 |

| English Catholic | 570,552 | 627,487 | 90.9 |

| French Public | 35,122 | 48,521 | 72.4 |

| French Catholic | 76,572 | 110,509 | 69.3 |

| Total | 2,049,953 | 2,340,002 | 87.6 |

Of the 10 largest school boards by school building square footage, six had utilization rates above the provincial average: the Durham DSB (109.5 per cent), the Halton DSB (99.1 per cent), the Waterloo Region DSB (96.7 per cent), the York Region DSB (96.0 per cent), the Thames Valley DSB (93.9 per cent) and the Ottawa-Carleton DSB (94.1 per cent).

| School Board | Number of Enrolled Students | Capacity (students) | Utilization Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto DSB | 236,109 | 294,810 | 80.1 |

| Peel DSB | 148,402 | 178,857 | 83.0 |

| York Region DSB | 128,267 | 133,546 | 96.0 |

| Toronto Catholic DSB | 85,003 | 100,941 | 84.2 |

| Thames Valley DSB | 82,880 | 88,310 | 93.9 |

| Ottawa-Carleton DSB | 76,059 | 80,858 | 94.1 |

| Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB | 71,040 | 88,424 | 80.3 |

| Durham DSB | 78,595 | 71,786 | 109.5 |

| Waterloo Region DSB | 64,879 | 67,112 | 96.7 |

| Halton DSB | 66,816 | 67,427 | 99.1 |

| All other school boards | 1,011,907 | 1,167,931 | 86.6 |

| Total | 2,049,953 | 2,340,002 | 87.6 |

Although the average school utilization rate was 87.6 per cent, utilization varied across schools. There were 3,392 schools with utilization rates below 100 per cent, which included 858 schools with utilization rates below 60 per cent (also referred to as underutilized schools)[21] and 2,534 schools with utilization rates between 60 per cent and 100 per cent. In contrast, 1,458 schools had utilization rates over 100 per cent. Schools with utilization rates over 100 per cent are experiencing capacity pressures and are referred to as overcapacity.

| Utilization Rate | Number of Schools | Share of Schools (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Under 60 per cent | 858 | 17.7 |

| Between 60 and 100 per cent | 2,534 | 52.2 |

| Over 100 per cent | 1,458 | 30.1 |

| Total | 4,850 | 100.0 |

The English Catholic system had the highest proportion of overcapacity schools, with 35.2 per cent of schools operating above 100 per cent utilization, followed by the English Public system (29.7 per cent of schools), the French Public system (22.2 per cent of schools) and the French Catholic system (15.7 per cent of schools).

In terms of underutilization, defined as usage of less than 60 per cent of spaces in a school, the French Catholic system had the highest proportion of underutilized schools, at 42.3 per cent, followed by the French Public system (38.9 per cent of schools), the English Catholic system (16.2 per cent of schools) and the English Public system (14.6 per cent of schools).

| School System | Number of Schools with Utilization Rates of: | Percentage of Schools with Utilization Rates of: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 60% | 60% – 100% | > 100% | < 60% | 60% – 100% | > 100% | |

| English Public | 443 | 1,688 | 902 | 14.6 | 55.7 | 29.7 |

| English Catholic | 215 | 647 | 469 | 16.2 | 48.6 | 35.2 |

| French Public | 65 | 65 | 37 | 38.9 | 38.9 | 22.2 |

| French Catholic | 135 | 134 | 50 | 42.3 | 42.0 | 15.7 |

| Total | 858 | 2,534 | 1,458 | 17.7 | 52.2 | 30.1 |

Of the 10 largest school boards by school building square footage, the Durham DSB had the highest proportion of overcapacity schools, with 69.2 per cent of schools operating above 100 per cent utilization, followed by the Thames Valley DSB (40.6 per cent of schools), the Waterloo Region DSB (39.0 per cent of schools), the York Region DSB (38.0 per cent of schools) and the Ottawa-Carleton DSB (35.4 per cent of schools).

In terms of underutilization, of the 10 largest school boards by school building square footage, the Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB had the highest proportion of schools operating at less than 60 per cent capacity, with 27.8 per cent of schools underutilized, followed by the Toronto Catholic DSB (23.0 per cent of schools), the Toronto DSB (18.7 per cent of schools), the Ottawa-Carleton DSB (12.9 per cent of schools) and the Peel DSB (12.7 per cent of schools).

| School Board | Number of Schools with Utilization Rates of: | Percentage of Schools with Utilization Rates of: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 60% | 60% – 100% | > 100% | < 60% | 60% – 100% | > 100% | |

| Toronto DSB | 108 | 381 | 89 | 18.7 | 65.9 | 15.4 |

| Peel DSB | 33 | 180 | 47 | 12.7 | 69.2 | 18.1 |

| York Region DSB | 15 | 117 | 81 | 7.0 | 54.9 | 38.0 |

| Toronto Catholic DSB | 47 | 101 | 56 | 23.0 | 49.5 | 27.5 |

| Thames Valley DSB | 12 | 83 | 65 | 7.5 | 51.9 | 40.6 |

| Ottawa-Carleton DSB | 19 | 76 | 52 | 12.9 | 51.7 | 35.4 |

| Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB | 42 | 76 | 33 | 27.8 | 50.3 | 21.9 |

| Durham DSB | 4 | 36 | 90 | 3.1 | 27.7 | 69.2 |

| Waterloo Region DSB | 4 | 71 | 48 | 3.3 | 57.7 | 39.0 |

| Halton DSB | 9 | 63 | 38 | 8.2 | 57.3 | 34.5 |

| All other school boards | 565 | 1,350 | 859 | 20.4 | 48.7 | 31.0 |

| Total | 858 | 2,534 | 1,458 | 17.7 | 52.2 | 30.1 |

Student Spaces in Overcapacity and Underutilized Schools

Across the 1,458 schools that were overcapacity (utilization over 100 per cent) in the 2023-24 school year, there were 150,881 more students than spaces. Of this amount, the FAO estimates that 112,274 students were accommodated through 4,893 portables and 38,607 students were accommodated through other means, such as larger class sizes or teachers holding classrooms in non-classroom spaces.

Across the 3,392 schools that were undercapacity (utilization less than 100 per cent) in the 2023-24 school year, there were 440,930 more spaces than students. Of this amount, there were 198,481 available spaces at 858 underutilized schools (utilization rates below 60 per cent) and 242,449 available spaces at 2,534 schools with utilization rates above 60 per cent but below 100 per cent.

| Utilization Rate | Number of Schools | Overcapacity Students | Available Spaces |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 60 per cent | 858 | – | 198,481 |

| Between 60 and 100 per cent | 2,534 | – | 242,449 |

| Over 100 per cent | 1,458 | 150,881 | – |

| Total | 4,850 | 150,881 | 440,930 |

6. Cost to Address Capacity Pressures

The FAO estimates that school enrolment will increase by 89,996 students over the 10-year period to 2033-34, from 2.05 million in 2023-24 to 2.14 million in 2033-34, representing an average annual growth rate of 0.4 per cent.[22] When combined with the 150,881 overcapacity students (as of the 2023-24 school year) and the projected 10-year enrolment growth of 89,996 students, the FAO estimates that school boards will be required to address total capacity pressures of 240,878 students in 2033-34.

To address capacity pressures, after accounting for projected enrolment growth in undercapacity schools, school boards can change school boundary areas, use portables for temporary capacity pressures, or build new schools to meet permanent capacity pressures. Based on the FAO’s review of the Ministry of Education’s programs and directives, and school boards’ policies, the FAO estimates that the projected capacity pressure of 240,878 students in 2033-34 could be addressed in the following ways:[23]

- A portion of the estimated change in enrolment over the next 10 years is expected to occur in areas with undercapacity schools that can accept more students. The FAO estimates that enrolment growth in undercapacity schools could offset capacity pressures by 23,408 students in 2033-34.

- School boards can change catchment areas to optimize the utilization of spaces across schools. The FAO assumes that school boards could use boundary area changes to optimize the utilization rates of schools for existing and future capacity pressures based on current policies and guidelines. The FAO estimates that these boundary area changes could offset capacity pressures by 39,225 students.

- School boards are able to offset temporary capacity pressures by using portables. The FAO assumes that, for schools that are overcapacity, school boards could use a portable rather than build a new school, if the capacity pressure is expected to be temporary. The FAO projects that the use of portables for temporary capacity pressures would require 239 portables for 6,058 students in 2033-34.[24]

- School boards can build new schools. After accounting for the first three factors, the FAO estimates that 172,187 student spaces will need to be built by 2033-34 to address permanent capacity pressures. The FAO estimates that to create 172,187 new school spaces, the Province would need to build the equivalent of 227 new schools at a cost of $9.8 billion over 10 years.

Cost by School System and School Board

As noted above, in order to address projected capacity pressures in 2033-34, the FAO estimates that the Province would need to build the equivalent of 227 new schools to create 172,187 student spaces at a cost of $9.8 billion. Of the $9.8 billion cost, the FAO estimates that $6.2 billion would be for the English Public system, $3.2 billion for the English Catholic system, $113 million for the French Public system and $219 million for the French Catholic system. As a share of CRV, the total cost is highest for the English Catholic system (9.9 per cent), followed by the English Public system (7.7 per cent), French Public system (3.7 per cent) and French Catholic system (3.2 per cent).

| School System | Number of New Student Spaces Required by 2033-34 | 10-year Cost to Build New Schools ($ millions) | Cost as Share of CRV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| English Public | 109,945 | 6,215 | 7.7 |

| English Catholic | 56,828 | 3,213 | 9.9 |

| French Public | 1,898 | 113 | 3.7 |

| French Catholic | 3,516 | 219 | 3.2 |

| Total | 172,187 | 9,761 | 7.9 |

Of the 10 largest school boards by school building square footage, the Durham DSB has the highest 10-year cost at $880 million, or 24.4 per cent of the total value of its schools. This is due to a combination of Durham DSB’s above average school utilization rate in 2023-24 (109.5 per cent compared to the provincial average of 87.6 per cent) and above average projected enrolment growth (0.9 per cent average annual growth to 2033-34 compared to the provincial average of 0.4 per cent). This is followed by the York Region DSB ($553 million, 8.8 per cent of CRV), the Ottawa-Carleton DSB ($494 million, 11.8 per cent of CRV), the Thames Valley DSB ($490 million, 11.1 per cent of CRV), the Halton DSB ($464 million, 14.2 per cent of CRV) and the Waterloo Region DSB ($445 million, 13.9 per cent of CRV).

| School Board | Number of New Student Spaces Required by 2033-34 | 10-year Cost to Build New Schools ($ millions) | Cost as Share of CRV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto DSB | 5,346 | 320 | 2.0 |

| Peel DSB | 6,085 | 360 | 4.4 |

| York Region DSB | 9,966 | 553 | 8.8 |

| Toronto Catholic DSB | 3,159 | 181 | 3.5 |

| Thames Valley DSB | 8,758 | 490 | 11.1 |

| Ottawa-Carleton DSB | 8,795 | 494 | 11.8 |

| Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB | 3,346 | 199 | 4.6 |

| Durham DSB | 16,625 | 880 | 24.4 |

| Waterloo Region DSB | 7,804 | 445 | 13.9 |

| Halton DSB | 8,382 | 464 | 14.2 |

| All other school boards | 93,921 | 5,375 | 8.3 |

| Total | 172,187 | 9,761 | 7.9 |

7. Analysis of the Province’s School Board Capital Plan

The Province’s 10-year capital plan, as outlined in the 2024 Ontario Budget, allocates a total of $23.1 billion to the education sector for infrastructure investments from 2024-25 to 2033-34. Of this amount, the FAO estimates that $18.7 billion is specifically designated for capital investments in school buildings, while $4.4 billion is earmarked for other assets (e.g., land, machinery, equipment, information technology) and for other education sector programs (e.g., child care). Of the $18.7 billion in funding for school buildings, the FAO estimates that a total of $12.5 billion will be available for condition improvement and $6.2 billion for capacity expansion.

Figure 7.1FAO estimate of the 10-year school building capital funding allocation in the 2024 Ontario Budget, $ billions

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Comparing FAO Cost Estimates Against the 2024 Budget

As discussed in Chapters 4 and 6, the FAO estimates that over the next 10 years, it will cost $21.7 billion to clear the school building infrastructure backlog and maintain schools in a state of good repair, and $9.8 billion to build new schools to address permanent capacity pressures. This represents a total projected cost of $31.4 billion over 10 years. In comparison, the 2024 Ontario Budget capital plan allocates an estimated $18.7 billion over 10 years. This represents an estimated funding shortfall over 10 years of $12.7 billion.

Figure 7.2FAO estimate of the 2024 Ontario Budget 10-year capital plan funding shortfall for school buildings, $ billions

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

Infrastructure Backlog and State of Good Repair

The FAO estimates that it would cost $21.7 billion to clear the infrastructure backlog and keep school buildings in a state of good repair over the next 10 years. In contrast, the 2024 budget has allocated $12.5 billion over 10 years. If funded at this level, the FAO estimates that after 10 years, the percentage of school buildings that are not in a state of good repair would increase from 37.4 per cent in 2023-24 to 74.6 per cent in 2033-34. By 2033-34, the infrastructure backlog would grow from $6.5 billion in 2023-24 to $22.1 billion.

Addressing Capacity Pressures

The FAO estimates that 172,187 student spaces will need to be built by 2033-34 to address permanent capacity pressures, at a cost of $9.8 billion. In contrast, the 2024 budget has allocated $6.2 billion, which the FAO estimates is sufficient to create 109,946 new student spaces by 2033-34. This would result in an estimated 68,299 more students than permanent school spaces in 2033-34, a decrease of 54.7 per cent from the 150,881 overcapacity students in the 2023-24 school year. The estimated 68,299 overcapacity students in 2033-34 could be accommodated by using 2,901 portables, which is a decrease of 1,992 portables (40.7 per cent) from the 4,893 portables used to address capacity pressures in 2023-24.

Appendix

A. How School Boards Address Capacity Pressures

School boards forecast enrolment by taking into account demographic projections, age distributions and other factors, such as housing starts. These enrolment projections are then compared to existing on-the-ground, permanent classroom capacity to determine pressures. School boards can then address these pressures by using portables, moving students through school boundary area changes, or proposing to build new schools. For schools with enrolment significantly below capacity, there is currently no process in place to close the school, as the Province placed a moratorium on school closures in 2017.[25]

Portables

School boards evaluate capacity pressure by comparing current permanent classroom capacity to long-term enrolment projections. If enrolment is above the permanent classroom capacity for only part of the long-term projection, then the capacity pressure is deemed to be temporary and portables are recommended as the solution. Portables may also be used to accommodate students during the construction of a new school. Portables can be quickly deployed and have low upfront cost, but they are not permanent solutions. The Ministry of Education does not account for portable capacity when evaluating capacity pressures.

Boundary Reviews

The Ministry of Education evaluates capacity pressure after considering reasonable opportunities to move students from overcapacity schools to undercapacity schools through changes to school catchment areas (i.e., conducting a boundary review). Proposals are brought to the school board’s trustees and must indicate a recommendation, a rationale for the boundary change and any potential impacts. When deciding on a school boundary change, considerations include historical and projected enrolment for the schools in question, proximity to and impact on other schools, facility statistics and conditions, school program offerings, transportation requirements, temporary accommodation needs (i.e., portables), future planning, geographic barriers, municipal planning projects, community support, and recent boundary changes. Remote school boards have limited ability to change catchment areas to redistribute students due to large geographic distance between schools.

Building a New School

To build a new school, school boards can submit a proposal to the Ministry of Education through the Capital Priorities Program, which is evaluated based on the urgency of enrolment pressures faced by the schools and all neighbouring schools, the condition of the school (if the proposal is to replace a deteriorating school with a new larger school), and the need for French-language access. The Ministry of Education also prioritizes projects that are most likely to be completed within a shorter time period and within the proposed timelines.[26] Finally, these proposals are considered and prioritized within the overall capital funding envelope provided to the Ministry of Education as part of the annual provincial budget process.

B. Enrolment Projection Analysis

The FAO projects enrolment based on a forecast of the Ontario population ages 4 to 17 and an assumed enrolment rate.

The FAO projects that the Ontario population aged 4 to 17 will increase from 2.29 million in 2023-24 to 2.33 million in 2033-34. This population forecast reflects changes to federal immigration targets announced in March and November 2024, and, as of the writing of this report, is lower than other publicly available population forecasts that do not reflect the federal government’s changes to immigration targets.[27]

Based on this population projection and an assumed enrolment rate that returns to pre-pandemic levels,[28] the FAO projects total enrolment will rise from 2.05 million in 2023-24 to 2.14 million in 2033-34, which is an increase of 89,996 students.

Figure B.1FAO projection for total school board enrolment to 2033-34

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Province.

By system, the FAO projects that the English Public school system will experience the largest enrolment growth over the next 10 years, with 0.5 per cent average annual growth and an increase of 67,021 students. The English Catholic system follows, with 0.4 per cent average annual growth and an increase of 22,294 students. The French Public and French Catholic systems are expected to grow at 0.1 per cent annually and to add 217 and 465 students, respectively.

| School System | Enrolment in 2023-24 |

Projected Enrolment in 2033-34 |

Projected Change in Enrolment |

Average Annual Growth Rate, % (2023-24 to 2033-34) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English Public | 1,367,708 | 1,434,728 | 67,021 | 0.5 |

| English Catholic | 570,552 | 592,846 | 22,294 | 0.4 |

| French Public | 35,122 | 35,339 | 217 | 0.1 |

| French Catholic | 76,572 | 77,037 | 465 | 0.1 |

| Total | 2,049,953 | 2,139,950 | 89,996 | 0.4 |

Of the 10 largest school boards by school building square footage, three are expected to have average annual enrolment growth rates above the provincial average: the Durham DSB (0.9 per cent), the Waterloo Region DSB (0.7 per cent) and the Thames Valley DSB (0.5 per cent).

| School Board | Enrolment in 2023-24 |

Projected Enrolment in 2033-34 |

Projected Change in Enrolment |

Average Annual Growth Rate, % (2023-24 to 2033-34) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto DSB | 236,109 | 246,584 | 10,475 | 0.4 |

| Peel DSB | 148,402 | 154,555 | 6,153 | 0.4 |

| York Region DSB | 128,267 | 130,666 | 2,399 | 0.2 |

| Toronto Catholic DSB | 85,003 | 84,457 | -547 | -0.1 |

| Thames Valley DSB | 82,880 | 87,517 | 4,636 | 0.5 |

| Ottawa-Carleton DSB | 76,059 | 78,560 | 2,500 | 0.3 |

| Dufferin-Peel Catholic DSB | 71,040 | 70,655 | -386 | -0.1 |

| Durham DSB | 78,595 | 85,886 | 7,291 | 0.9 |

| Waterloo Region DSB | 64,879 | 69,492 | 4,614 | 0.7 |

| Halton DSB | 66,816 | 68,381 | 1,564 | 0.2 |

| All other school boards | 1,011,901 | 1,063,199 | 51,297 | 0.5 |

| Total | 2,049,953 | 2,139,950 | 89,996 | 0.4 |

Graphical Descriptions

| Region | Number of English Schools | Number of French Schools |

|---|---|---|

| Toronto | 1,719 | 67 |

| Hamilton – Niagara Peninsula | 577 | 37 |

| Ottawa | 404 | 149 |

| Kitchener – Waterloo – Barrie | 437 | 26 |

| Northeast / Nord-est | 226 | 129 |

| Windsor – Sarnia | 200 | 33 |

| London | 212 | 13 |

| Kingston – Pembroke | 202 | 14 |

| Muskoka – Kawarthas | 147 | 2 |

| Northwest / Nord-ouest | 115 | 14 |

| Stratford – Bruce Peninsula | 125 | 2 |

| Total | 4,364 | 486 |

| Region | Average CRV / Sq Ft. | Average students per school |

|---|---|---|

| Toronto | 397.6-422.3 | 405-474 |

| Hamilton – Niagara Peninsula | 422.3-426.7 | 474-496 |

| Ottawa | 397.6-422.3 | 340-405 |

| Kitchener – Waterloo – Barrie | 422.3-426.7 | 405-474 |

| Northeast / Nord-est | 488.8-689.6 | 207-302 |

| Windsor – Sarnia | 426.7-457.2 | 340-405 |

| London | 397.6-422.3 | 474-496 |

| Kingston – Pembroke | 426.7-457.2 | 207-302 |

| Muskoka – Kawarthas | 457.2-488.8 | 302-340 |

| Northwest / Nord-ouest | 488.8-689.6 | 207-302 |

| Stratford – Bruce Peninsula | 457.2-488.8 | 302-340 |

| Total | 397.6-689.6 | 207-496 |

| Implied Age (years) | Deterioration Curve | State of Good Repair (SOGR) Target | Replacement Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 80 | 20 |

| 3 | 99 | 80 | 20 |

| 5 | 99 | 80 | 20 |

| 7 | 98 | 80 | 20 |

| 9 | 97 | 80 | 20 |

| 11 | 96 | 80 | 20 |

| 13 | 94 | 80 | 20 |

| 15 | 92 | 80 | 20 |

| 17 | 89 | 80 | 20 |

| 19 | 85 | 80 | 20 |

| 21 | 81 | 80 | 20 |

| 23 | 76 | 80 | 20 |

| 25 | 69 | 80 | 20 |

| 27 | 62 | 80 | 20 |

| 29 | 55 | 80 | 20 |

| 31 | 47 | 80 | 20 |

| 33 | 40 | 80 | 20 |

| 35 | 33 | 80 | 20 |

| 37 | 26 | 80 | 20 |

| 39 | 21 | 80 | 20 |

| 41 | 17 | 80 | 20 |

| 43 | 13 | 80 | 20 |

| 45 | 10 | 80 | 20 |

| 47 | 8 | 80 | 20 |

| 49 | 6 | 80 | 20 |

| 51 | 5 | 80 | 20 |

| 53 | 4 | 80 | 20 |

| 55 | 3 | 80 | 20 |

| 57 | 2 | 80 | 20 |

| 59 | 2 | 80 | 20 |

| 61 | 2 | 80 | 20 |

| 63 | 2 | 80 | 20 |

| 65 | 1 | 80 | 20 |

| Condition | Number of Schools |

|---|---|

| Schools that should be replaced | 32 |

| Schools that require rehabilitation | 1,781 |

| Schools in a State of Good Repair | 3,037 |

| Total | 4,850 |

| FAO Cost Estimate | Cost ($ billions) |

|---|---|

| Cost to clear the current school buildings infrastructure backlog | 6.5 |

| Cost to maintain school buildings in a state of good repair over 10 years | 15.2 |

| Total cost | 21.7 |

| School Building Capital Funding Allocation | Funding ($ billions) |

|---|---|

| To address the infrastructure backlog and maintain state of good repair | 12.5 |

| To build new schools | 6.2 |

| Total for school buildings | 18.7 |

| Not for school buildings | 4.4 |

| Total education sector infrastructure funding | 23.1 |

| FAO Cost Estimate | 2024 Ontario Budget Capital Plan Funding | |

|---|---|---|

| Cost to clear infrastructure backlog and maintain the state of good repair | 21.7 | 12.5 |

| Cost to build new schools to address capacity pressures | 9.8 | 6.2 |

| Funding shortfall | – | 12.7 |

| Total | 21.7 | 21.7 |

| Year | Historical | FAO Projection |

|---|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 1,961,010 | – |

| 2016-17 | 1,964,172 | – |

| 2017-18 | 1,977,444 | – |

| 2018-19 | 1,993,509 | – |

| 2019-20 | 2,008,315 | – |

| 2020-21 | 2,005,172 | – |

| 2021-22 | 1,996,097 | – |

| 2022-23 | 2,014,429 | – |

| 2023-24 | 2,049,953 | – |

| 2024-25 | – | 2,087,105 |

| 2025-26 | – | 2,095,129 |

| 2026-27 | – | 2,098,503 |

| 2027-28 | – | 2,101,398 |

| 2028-29 | – | 2,108,146 |

| 2029-30 | – | 2,118,145 |

| 2030-31 | – | 2,125,075 |

| 2031-32 | – | 2,130,386 |

| 2032-33 | – | 2,135,250 |

| 2033-34 | – | 2,139,950 |

Footnotes

[1] The 4,850 schools are located in approximately 4,500 buildings, as some schools share the same building.

[2] All subsequent references to “school boards” in this report refer to district school boards (DSBs).

[3] The current replacement value (CRV) of infrastructure refers to the estimated cost of rebuilding an asset with the equivalent capacity, functionality and performance as the original asset, based in today’s dollars.

[4] See Chapter 4 for more information on how the FAO calculates the infrastructure backlog.

[5] In this report, the FAO defines “classroom capacity” as permanent (i.e., on-the-ground) capacity in buildings and permanent structures; classroom capacity excludes portable capacity, which is intended to be temporary.

[6] According to the Ministry of Education Community Planning and Partnerships Guideline (2015), schools with utilization rates below 60 per cent are defined as “underutilized.”

[7] All subsequent references to “school boards” in this report refer to district school boards (DSBs).

[8] In addition to the Province’s 72 school boards, there are approximately 1,300 students who receive their education through 10 school authorities consisting of three geographically isolated boards, six hospital-based school authorities and one Protestant school board. School authorities are outside the scope of this report. There are also Provincial and Demonstration Schools and Consortium Centre Jules-Léger that are also outside the scope of this report.

[9] The 4,850 schools are located in approximately 4,500 buildings, as some schools share the same building.

[10] Economic regions as defined by Statistics Canada.

[11] The CRV is different from the net book value because it does not account for depreciation over time.

[12] See Appendix A in the Expert Panel on Capital Standards for Ontario Schools, Building Our Schools, Building Our Future: Report of the Expert Panel on Capital Standards for Ontario Schools, 2010.

[13] School buildings, which form the scope of analysis in this report, account for almost 90 per cent of school board infrastructure on a historical cost basis. Within school buildings, the FAO estimates that 1.3 per cent of the total square footage is for child care.

[14] The assessment team reviews site features, building structure, building envelope (exterior walls and roofs), interior components or finishes, and mechanical, fire and life safety, and electrical systems. Each year, about 20 per cent of schools are assessed.

[15] The FAO calculates FCI by dividing the cost of an asset’s total three-year repair and replacement need (its current year need, including prior years’ deferred maintenance, plus the estimated need over the next two years) by the building’s current replacement value.

[16] Rehabilitation is the repair of all or part of an asset, extending its life beyond that of the original asset, without adding to its capacity, functionality or performance. Rehabilitation is different from maintenance, which is the routine activities performed on an asset that maximize service life and minimize service disruptions. Assets are rehabilitated to a state of good repair (the repair target) and not to a new condition.

[17] Replacement results in a new or as-new asset with an equivalent capacity, functionality and performance as the original asset. Replacement is different from rehabilitation, as replacement rebuilds the entire asset.

[18] Importantly, being below SOGR does not imply that the building is in a state of disrepair. Rather, it serves as an analytical benchmark to assess when an asset requires rehabilitation projects, such as roof repairs, and updates to heating, ventilation and air conditioning units, and when an asset should be replaced.

[19] The FAO’s infrastructure backlog definition is based on the definition used by the Ministry of Infrastructure. Other infrastructure backlog definitions are used by other organizations, including the total repair and replacement spending need required for all school buildings, whether or not in a state of good repair, and over a longer time period, for example five years rather than the three years used by the FAO.

[20] In this report, the FAO defines “classroom capacity” as permanent (i.e., on-the-ground) capacity in buildings and permanent structures; classroom capacity excludes portable capacity, which is intended to be temporary. Student capacity is measured based on benchmarks and guidelines developed in 2010 by the Expert Panel on Capital Standards, in which a certain amount of square footage per student is recommended, so that the facilities are able to provide students with a reasonably equitable range of programs and services. For example, the recommended square footage of instructional space per elementary student ranges from about 100 to 150, depending on the total level of school enrolment. See Building Our Schools, Building Our Future: Report of the Expert Panel on Capital Planning for Ontario Schools, Capital Programs Branch, 2010.

[21] According to the Ministry of Education Community Planning and Partnerships Guideline (2015), schools with utilization rates below 60 per cent are defined as “underutilized.”

[22] For more analysis, see Appendix B.

[23] See Appendix A for more information on how school boards address capacity pressures.

[24] The FAO’s projection of 239 portables for 6,058 students in 2033-34 would be a significant reduction from the 4,893 portables for 112,274 students in 2023-24. The FAO’s projected decrease in the number of portables is due to both a projected decline in enrolment in some schools currently using portables and the forecast that capacity pressures in some schools currently using portables are not temporary, thus requiring a new school to be built.

[25] This moratorium was established when the Province asked school boards to not start any new Pupil Accommodation Reviews (PARs). Prior to the moratorium, school boards were able to close schools via a multi-step process where they would outline enrolment, utilization and recommendations in a report. This report would be presented to the affected community for consultation, and then to the school board’s trustees to make a final decision.

[26] Education Capital Programs and Policies Manual, Ministry of Education, April 2024.

[27] For example, the Ministry of Finance’s (MOF) demographic projection from October 2024 forecasts that the age 4 to 17 population will increase to 2.35 million by 2033. Compared to the MOF projection, the FAO’s population forecast includes the updated federal immigration targets announced in November 2024, resulting in a lower population projection.

[28] The enrolment rate of the Ontario population ages 4 to 17 averaged 91.2 per cent from 2015-16 to 2019-20.