Strong economic growth driving significant fiscal improvement

1 | Summary

This Economic and Budget Outlook report provides the FAO’s projection of the Ontario government’s fiscal position to 2026-27, based on information available up to March 28, 2022.

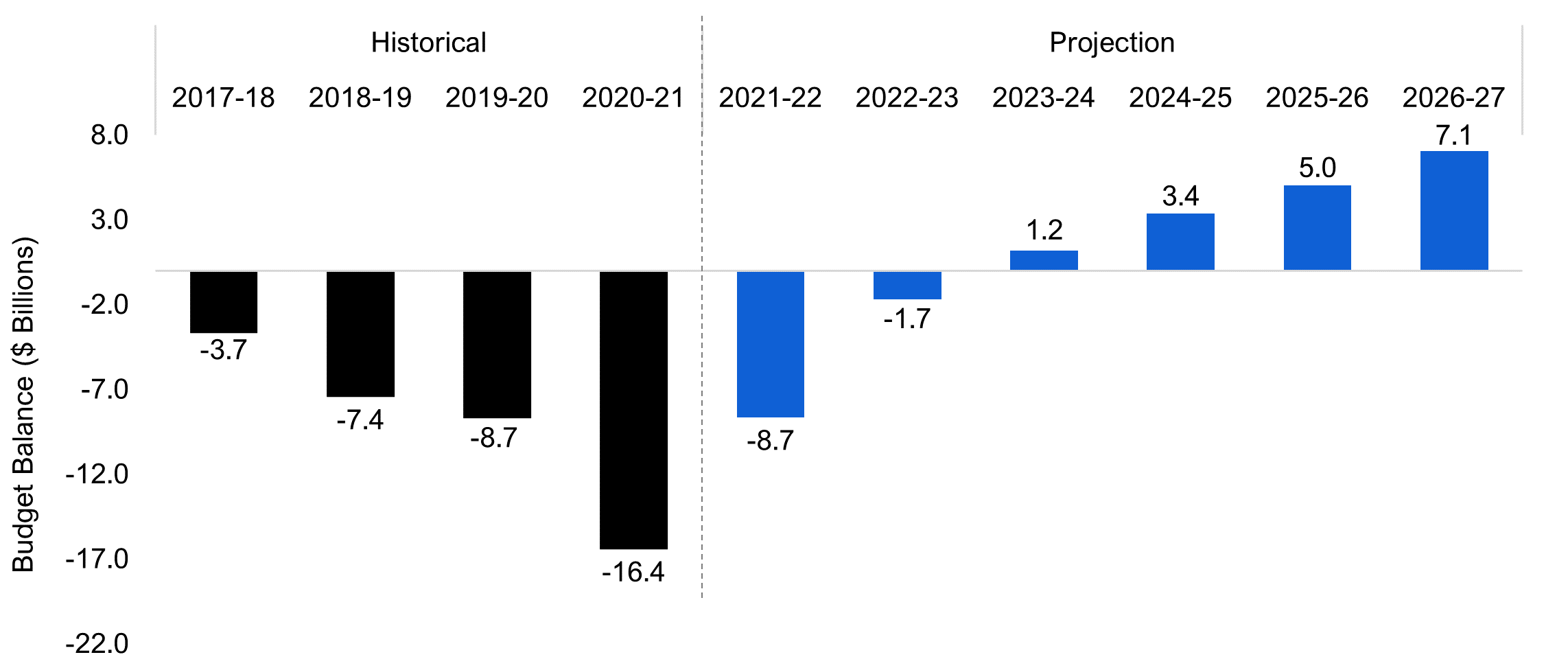

Balanced budget expected by 2023-24, followed by surpluses

After posting a $16.4 billion deficit for 2020-21, the FAO expects an $8.7 billion budget deficit in 2021-22, reflecting a pickup in revenue growth combined with slow program spending growth, due to a decline in temporary COVID-19-related spending. With strong revenue growth exceeding increases in program spending over the outlook, the FAO projects that under current policies, the Province will balance the budget by 2023-24 and run a $7.1 billion surplus by 2026-27.

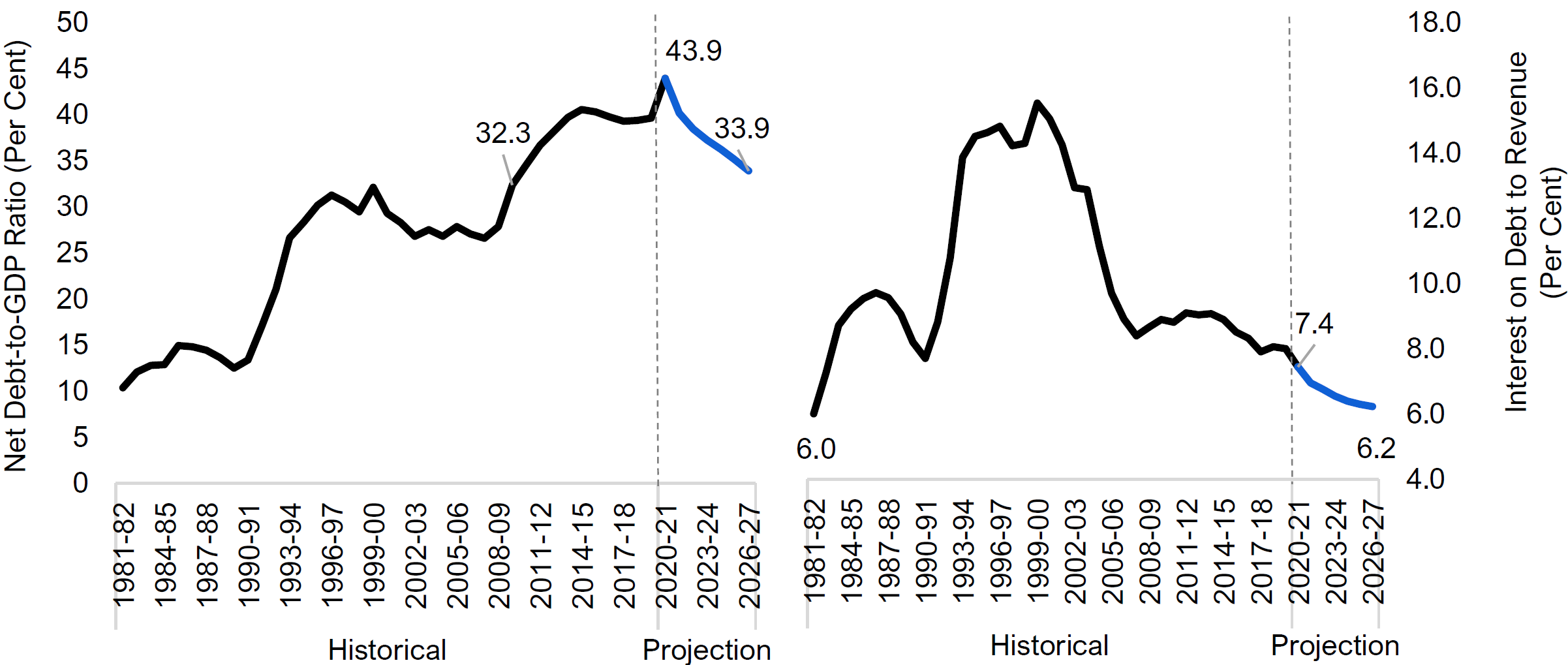

Net debt-to-GDP ratio to decline below pre-pandemic levels

The improved budget position combined with robust economic growth over the projection would lower the net debt-to-GDP ratio below pre-pandemic levels. By 2026-27, the FAO projects Ontario’s net debt-to-GDP ratio will fall to 33.9 per cent, the lowest since 2009-10. Interest on debt as a share of revenue is projected to decline to 6.2 per cent, below its pre-pandemic level of 8.0 per cent and the lowest since 1981-82.

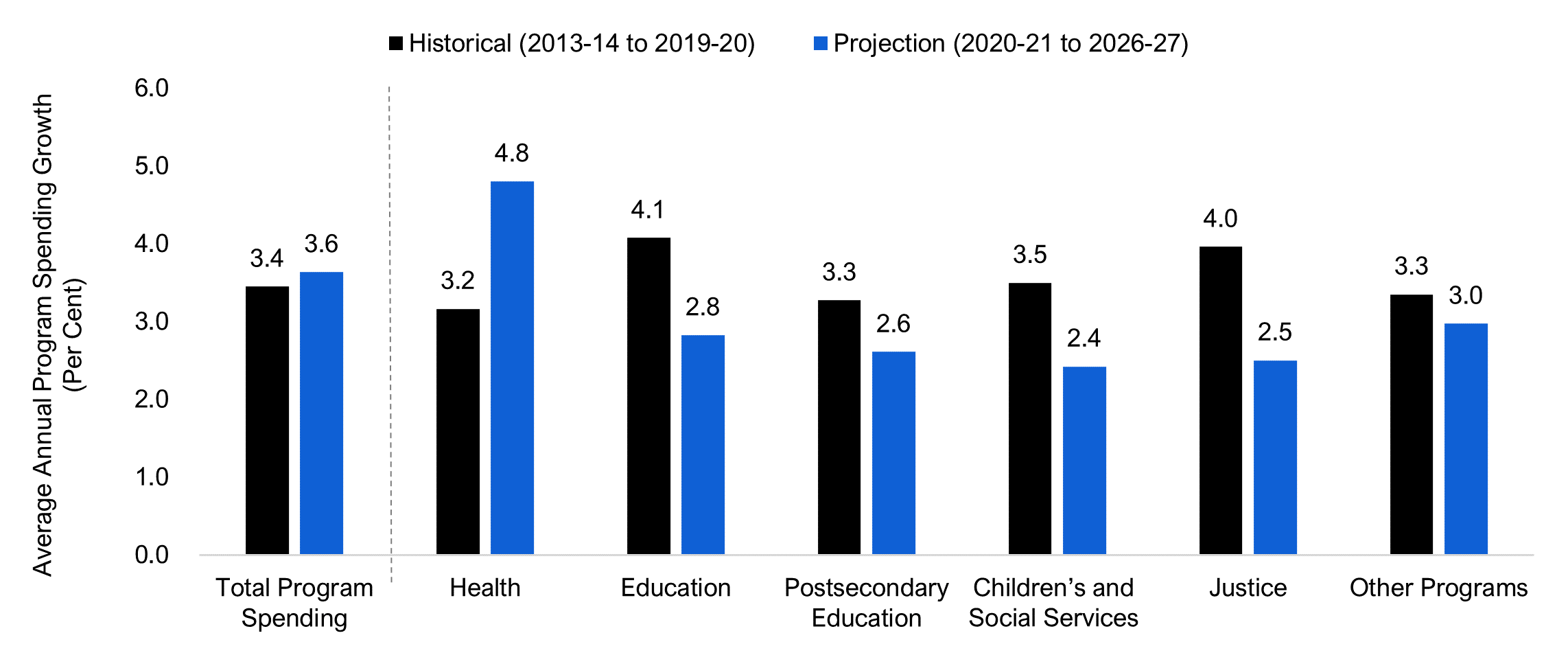

Program spending projected to grow above recent historical rate

The FAO projects that program spending will increase by an average annual rate of 3.6 per cent from 2020-21 to 2026-27, higher than the 3.4 per cent average annual growth rate from 2013-14 to 2019-20. This increase is in part due to long-term care homes spending commitments and the recently announced federal-provincial agreement to provide a ‘$10-a-day’ child care program. By program sector, health spending growth will be higher than the historical average (4.8 per cent over the projection compared to historical growth of 3.2 per cent), while all other program sectors will experience spending growth below the historical average.

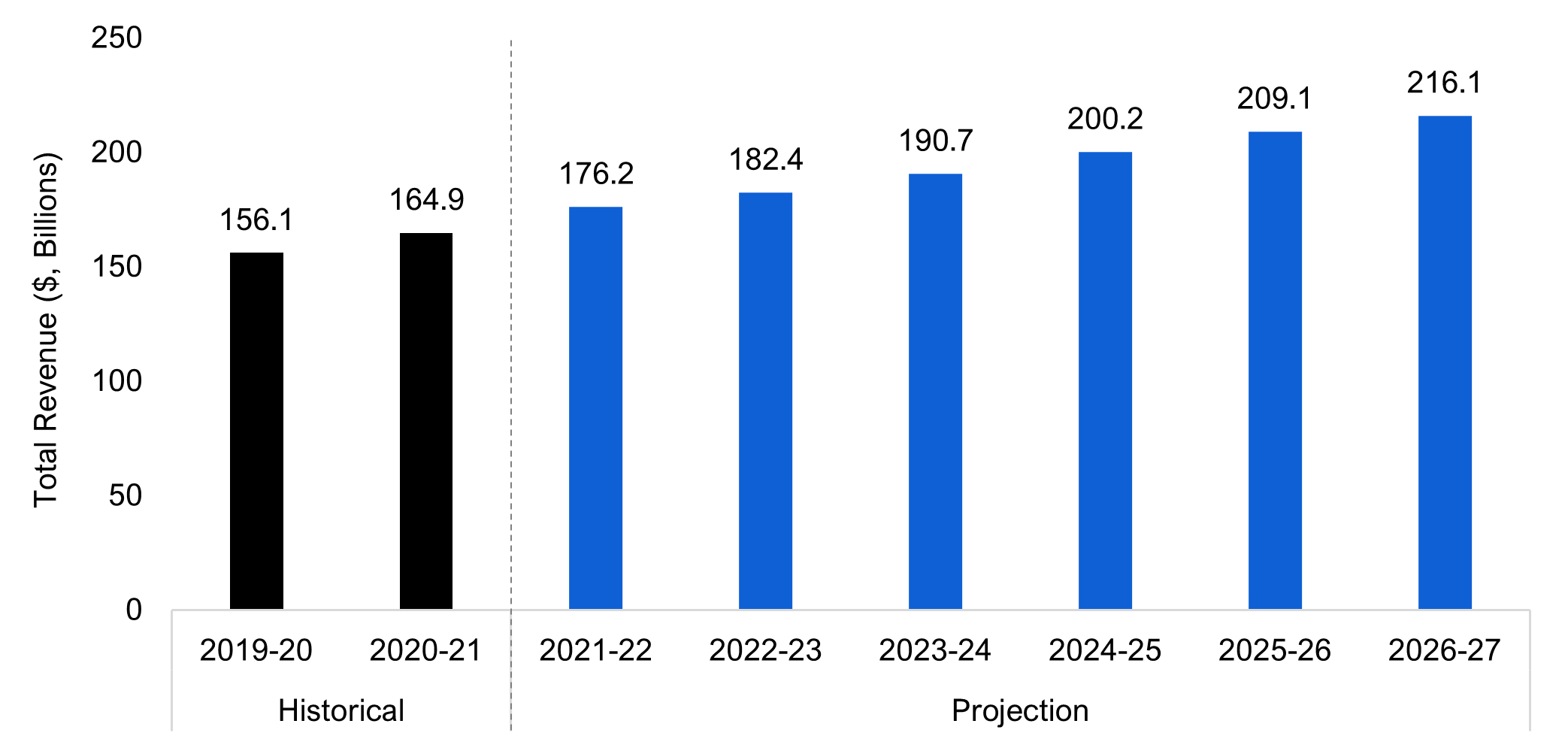

Strong economic growth and federal support are projected to lift revenues

Unprecedented federal income supplements to workers and businesses through the pandemic supported strong provincial revenue gains in 2020-21. Healthy revenue gains are projected to continue as near-term economic growth is expected to be robust, with nominal GDP growing by 11.9 per cent in 2021, the strongest growth since 1984, followed by a gain of 7.2 per cent in 2022.

Strong economic growth and increased federal transfers for the ‘$10-a-day’ child care program will lead to revenue growth of 4.8 per cent per year over 2020-21 to 2026-27, stronger than the 3.8 per cent average annual growth seen from 2013-14 to 2019-20.

2 | Budget and Debt Outlook

The FAO expects Ontario to return to balance in 2023-24, followed by surpluses

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Ontario’s budget deficit widened from $3.7 billion in 2017-18 to $8.7 billion in 2019-20. This was due in part to several policy decisions including the partial sale of Hydro One,[1] the cancellation of the cap and trade program,[2] numerous tax changes,[3] as well as the end of the debt retirement charge and Equalization payments to Ontario.[4]

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a large deterioration of Ontario’s deficit, which nearly doubled to $16.4 billion in 2020-21. This was primarily due to the large but temporary spending on COVID-19-related measures, offset partially by significant increases in federal transfer payments to the province.

The FAO projects that under current policies, Ontario’s budget position would improve from a deficit of $16.4 billion in 2020-21 to a surplus of $7.1 billion by 2026-27. Over the outlook, strong revenue growth is projected to outpace the rate of increase in program spending, leading to a significant improvement in Ontario’s budget balance.

Figure 2‑1 FAO projects a balanced budget by 2023-24, followed by surpluses

The Budget Balance is presented without the reserve.

Source: 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review and FAO

Accessible version

| Year | Budget Balance ($ Billions) | |

| Historical | 2017-18 | -3.7 |

| 2018-19 | -7.4 | |

| 2019-20 | -8.7 | |

| 2020-21 | -16.4 | |

| Projection | 2021-22 | -8.7 |

| 2022-23 | -1.7 | |

| 2023-24 | 1.2 | |

| 2024-25 | 3.4 | |

| 2025-26 | 5.0 | |

| 2026-27 | 7.1 |

The FAO’s deficit projection is based on current government revenue and program spending policies, the estimated impact of the Omicron wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and new program announcements made since the release of the Fall Economic Statement up to March 28, 2022. The FAO’s updated deficit outlook has improved since the release of its 2022 Budget Outlook Update (BOU), mainly due to upward revisions to the economic and revenue projections.

However, several uncertainties exist that could present challenges to Ontario’s economic and fiscal outlook. The war in Ukraine could exacerbate already elevated inflationary pressures and slow economic growth, while new government initiatives in the upcoming 2022 Ontario Budget would impact the FAO’s fiscal projection.

Lower deficits will improve Ontario’s fiscal sustainability indicators

Given the FAO’s outlook for declining budget deficits followed by surpluses, Ontario’s fiscal indicators are expected to improve over the projection after sharp pandemic-related deterioration in 2020-21. Under current policies, the province’s net debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to decline to 33.9 per cent by 2026-27, well below the 43.9 per cent recorded in 2020-21 and the lowest ratio since 2009-10.

Similarly, debt interest payments as a share of revenue are projected to decline from 7.4 per cent in 2020-21 to 6.2 per cent by 2026-27, the lowest ratio since 1981-82.

Figure 2‑2 FAO projects an improvement in Ontario’s fiscal sustainability indicators

Source: 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, Ontario Public Accounts, Ontario Economic Accounts and FAO.

Accessible version

| Year | Net Debt-to-GDP Ratio (Per Cent) | Interest on Debt to Revenue (Per Cent) | |

| Historical | 1981-82 | 10.4 | 6.0 |

| 1982-83 | 12.1 | 7.3 | |

| 1983-84 | 12.8 | 8.7 | |

| 1984-85 | 12.9 | 9.2 | |

| 1985-86 | 14.9 | 9.5 | |

| 1986-87 | 14.8 | 9.7 | |

| 1987-88 | 14.4 | 9.6 | |

| 1988-89 | 13.6 | 9.1 | |

| 1989-90 | 12.5 | 8.2 | |

| 1990-91 | 13.4 | 7.7 | |

| 1991-92 | 17.1 | 8.8 | |

| 1992-93 | 21.1 | 10.8 | |

| 1993-94 | 26.6 | 13.9 | |

| 1994-95 | 28.3 | 14.5 | |

| 1995-96 | 30.1 | 14.6 | |

| 1996-97 | 31.2 | 14.8 | |

| 1997-98 | 30.5 | 14.2 | |

| 1998-99 | 29.4 | 14.3 | |

| 1999-00 | 32.1 | 15.5 | |

| 2000-01 | 29.3 | 15.0 | |

| 2001-02 | 28.2 | 14.2 | |

| 2002-03 | 26.8 | 12.9 | |

| 2003-04 | 27.5 | 12.9 | |

| 2004-05 | 26.8 | 11.1 | |

| 2005-06 | 27.8 | 9.7 | |

| 2006-07 | 27.1 | 8.9 | |

| 2007-08 | 26.6 | 8.4 | |

| 2008-09 | 27.8 | 8.7 | |

| 2009-10 | 32.3 | 8.9 | |

| 2010-11 | 34.5 | 8.8 | |

| 2011-12 | 36.6 | 9.1 | |

| 2012-13 | 38.2 | 9.0 | |

| 2013-14 | 39.7 | 9.1 | |

| 2014-15 | 40.5 | 8.9 | |

| 2015-16 | 40.3 | 8.5 | |

| 2016-17 | 39.7 | 8.3 | |

| 2017-18 | 39.3 | 7.9 | |

| 2018-19 | 39.4 | 8.1 | |

| 2019-20 | 39.6 | 8.0 | |

| 2020-21 | 43.9 | 7.4 | |

| Projection | 2021-22 | 40.2 | 7.0 |

| 2022-23 | 38.4 | 6.8 | |

| 2023-24 | 37.2 | 6.5 | |

| 2024-25 | 36.2 | 6.4 | |

| 2025-26 | 35.1 | 6.3 | |

| 2026-27 | 33.9 | 6.2 |

Revenue outlook

The FAO expects revenues to increase from $156.1 billion in 2019-20 to $216.1 billion in 2026-27, an average annual growth rate of 4.8 per cent over the period. During the COVID-19 pandemic, revenues were buoyed by the significant increase in federal transfers to the province, as well as federal income supports for workers and businesses that bolstered provincial tax revenues. Near-term economic growth is expected to be robust, with nominal GDP growing by 11.9 per cent in 2021, the strongest growth since 1984, followed by a gain of 7.2 per cent in 2022, boosting revenue growth over the projection.

Figure 2‑3 Revenue growth projected to average 4.8 per cent from 2019-20 to 2026-27

Source: 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, Ontario Ministry of Finance, Ontario Public Accounts and FAO

Accessible version

| Year | Total Revenue ($, Billions) | |

| Historical | 2019-20 | 156.1 |

| 2020-21 | 164.9 | |

| Projection | 2021-22 | 176.2 |

| 2022-23 | 182.4 | |

| 2023-24 | 190.7 | |

| 2024-25 | 200.2 | |

| 2025-26 | 209.1 | |

| 2026-27 | 216.1 |

The FAO’s updated revenue projection includes: information in Ontario’s Third Quarter Finances, which showed significantly higher tax revenues, particularly for corporations taxes;[5] upward revisions in the FAO’s economic projection; and new federal and provincial policy announcements up to March 28, 2022. Policy announcements include:

- introducing a federal-provincial agreement for a ‘$10-a-day’ child care program that will increase federal transfers by $13.2 billion from 2022-23 to 2026-27;

- implementing a one-time increase in 2022-23 Canada Health Transfers from the federal government to clear the surgical backlog;[6]

- eliminating licence plate renewal fees and stickers and refunding fees paid since March 2020;

- removing tolls on Highways 412 and 418; and

- extending the freeze on college tuition to 2022-23.

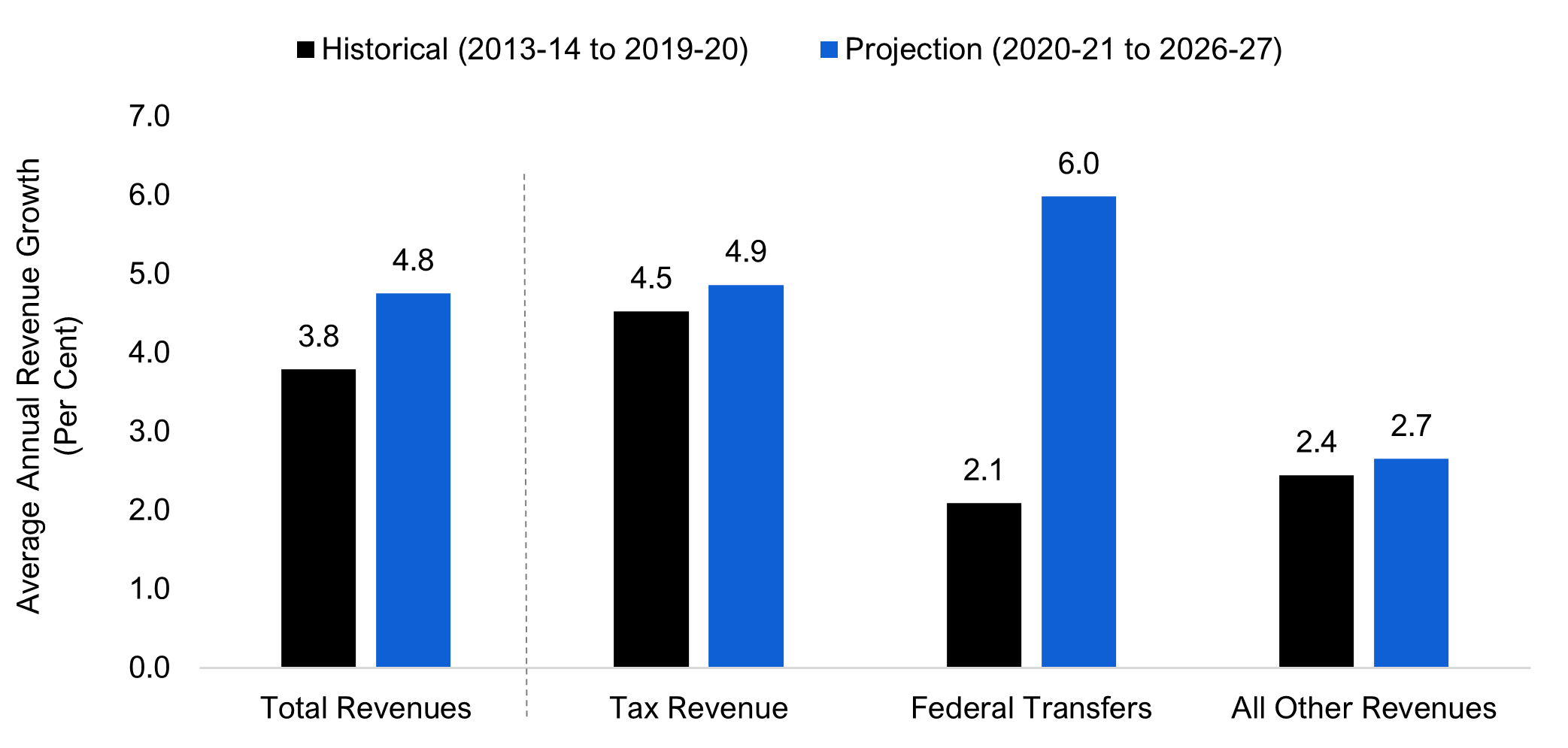

The 4.8 per cent average annual revenue growth projected over the 2020-21 to 2026-27 period is a full percentage point higher than the 3.8 per cent growth observed over the 2013-14 to 2019-20 period. The slower historical growth rate was due to weaker economic growth compared to the projection period,[7] as well as the cancellation of the cap and trade program, the introduction of numerous tax measures, the loss of revenue from one-time asset sales and the end of Equalization payments to Ontario.[8]

Figure 2‑4 Gains in tax revenues and federal transfers are projected to drive strong revenue growth

Source: 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, Ontario Ministry of Finance, Ontario Public Accounts and FAO

Accessible version

| Average Annual Revenue Growth (Per Cent) | ||

| Historical (2013-14 to 2019-20) | Projection (2020-21 to 2026-27) | |

| Total Revenues | 3.8 | 4.8 |

| Tax Revenue | 4.5 | 4.9 |

| Federal Transfers | 2.1 | 6.0 |

| All Other Revenues | 2.4 | 2.7 |

Tax revenues

Tax revenues are expected to grow at 4.9 per cent per year on average over the projection, above the 4.5 per cent growth during the recent past. This is broadly consistent with the FAO’s projection for strong economic growth over the next several years as the Ontario economy rebounds from the pandemic.

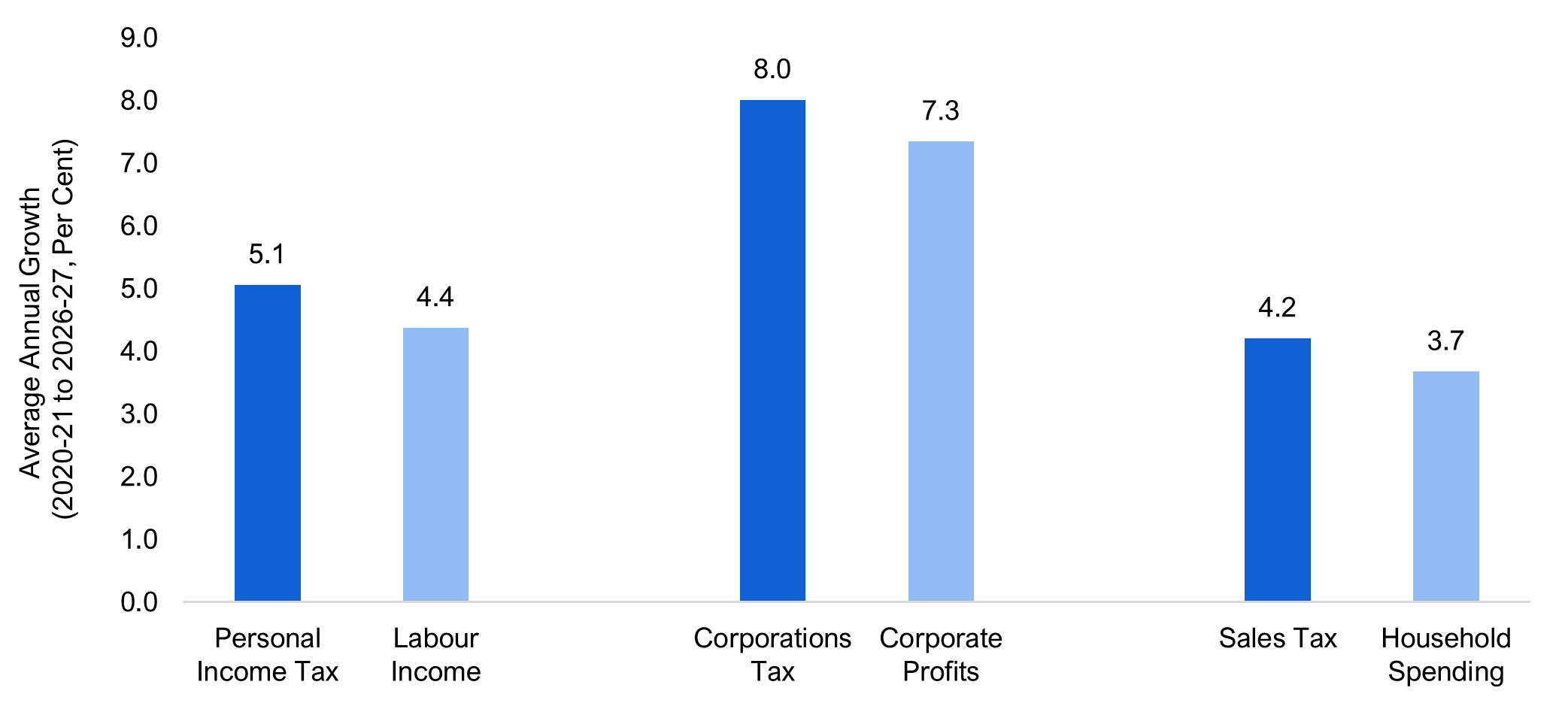

Figure 2‑5 Corporations tax is driving tax revenue growth over the outlook

Sources: Statistics Canada, Ontario Public Accounts, Ministry of Finance and FAO

Accessible version

| Average Annual Growth (2020-21 to 2026-27, Per Cent) | |

| Personal Income Tax | 5.1 |

| Labour Income | 4.4 |

| Corporations Tax | 8.0 |

| Corporate Profits | 7.3 |

| Sales Tax | 4.2 |

| Household Spending | 3.7 |

Personal income tax, corporations tax and sales tax represent about three-quarters of all tax revenues, and all three are expected to grow significantly over the projection, in line with their economic drivers.

- Personal income tax revenue is expected to grow at an average of 5.1 per cent per year over the projection, driven by gains in labour income of 4.4 per cent.

- Corporations tax revenue growth is projected to average 8.0 per cent over 2020-21 to 2026-27, driven by corporate profit growth of 7.3 per cent.

- Sales tax revenue is expected to grow by 4.2 per cent per year on average over the projection, driven by gains in household consumption of 3.7 per cent.

Federal transfers

Federal transfer payments are projected to grow at 6.0 per cent per year on average over the outlook, well above the 2.1 per cent growth observed from 2013-14 to 2019-20. Federal transfers rose substantially in 2020-21 and 2021-22 as the federal government increased support to the province during the pandemic. Despite the phasing out of temporary pandemic-related transfers in 2021-22, the Canada Health Transfer will continue to grow rapidly alongside the significant gains in nominal GDP,[9] while the federal-provincial agreement for a ‘$10-a-day’ child care program is expected to add $13.2 billion[10] in transfer revenues from 2022-23 to 2026-27.

Other revenues

Other revenues, which include income from government business enterprises as well as other non-tax revenues, are expected to grow at 2.7 per cent per year on average over the outlook (2020-21 to 2026-27), slightly above the historical rate of 2.4 per cent (2013-14 to 2019-20). The growth rate over the projection reflects the boost in revenues from robust near-term economic strength. In contrast, the slower growth rate over the historical period included the loss of revenues from the partial sale of Hydro One,[11] the cancellation of the cap and trade program,[12] the end of time limited revenue from one-time asset sales, and the end of the debt retirement charge.

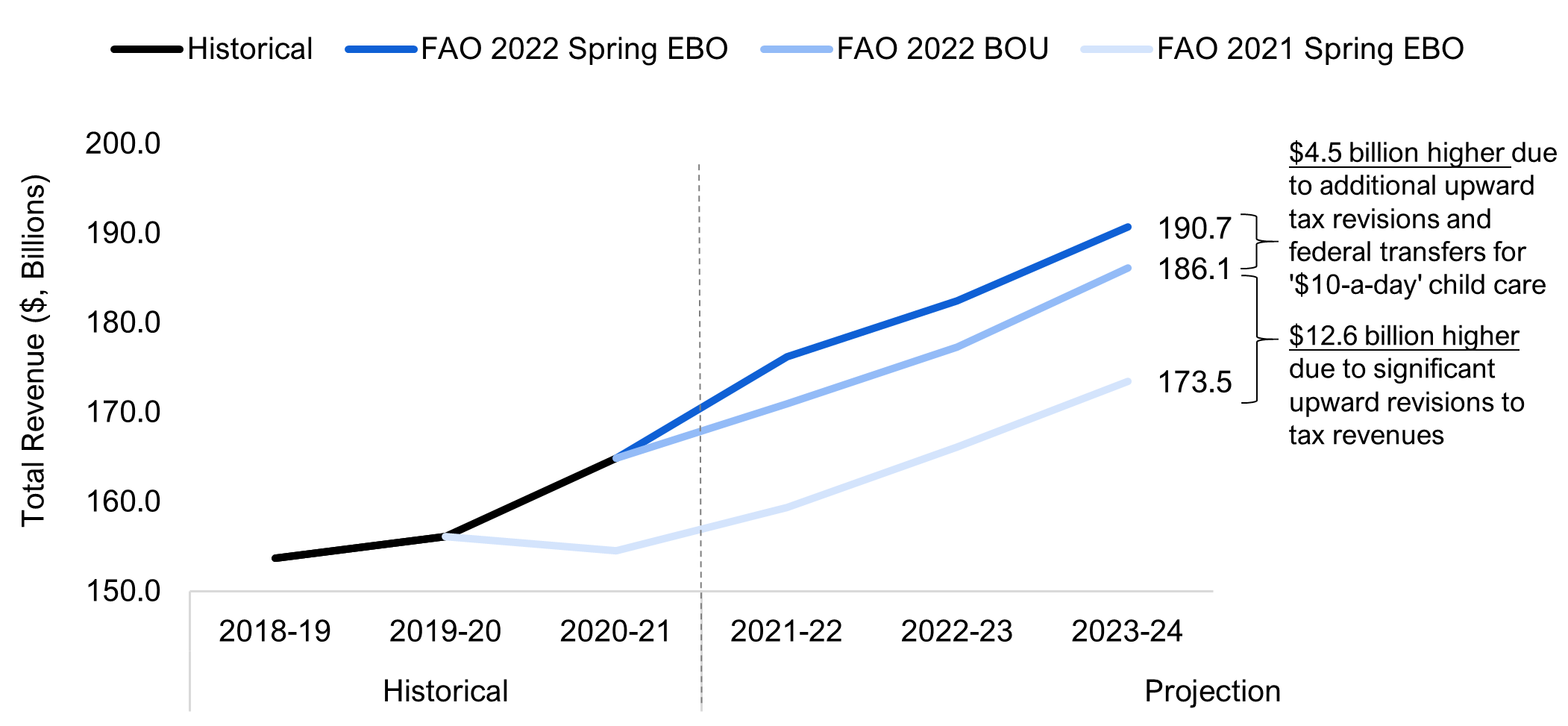

The FAO’s revenue projection has been revised up significantly over the past year

Since the FAO’s 2021 Spring EBO, the revenue projection has been revised up substantially. The FAO’s current revenue outlook is $17.2 billion higher in 2023-24 than was projected a year earlier.

In June 2021, the FAO projected that total revenue would reach $173.5 billion in 2023-24, based on the expectation that the pandemic would cause steep declines in economic activity and provincial revenue.[13] However, over subsequent months it became clear that federal income supports were substantially mitigating household and business income losses during the pandemic, supporting Ontario’s economic growth and tax revenues. This contributed to a $12.6 billion upward revision to the FAO’s updated revenue outlook in February 2022.

Since February, the FAO revised the revenue outlook up by an additional $4.5 billion by 2023-24, largely reflecting higher corporations tax revenue and the federal-provincial agreement for a ‘$10-a-day’ child care program which will significantly increase transfer revenues to the Province.

Figure 2‑6 FAO projects $17.2 billion higher revenue in 2023-24 than in the Spring 2021 outlook

Note: The projection in this figure only extends to 2023-24, which was the final year of the 2022 Budget Outlook Update projection.

Source: 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, Ontario Ministry of Finance and FAO

Accessible version

| Total Revenue ($, Billions) | |||||

| Year | Historical | FAO 2022 Spring EBO | FAO 2022 BOU | FAO 2021 Spring EBO | |

| Historical | 2018-19 | 153.7 | |||

| 2019-20 | 156.1 | ||||

| 2020-21 | 164.9 | 154.5 | |||

| Projection | 2021-22 | 176.2 | 171.0 | 159.4 | |

| 2022-23 | 182.4 | 177.3 | 166.1 | ||

| 2023-24 | 190.7 | 186.1 | 173.5 | ||

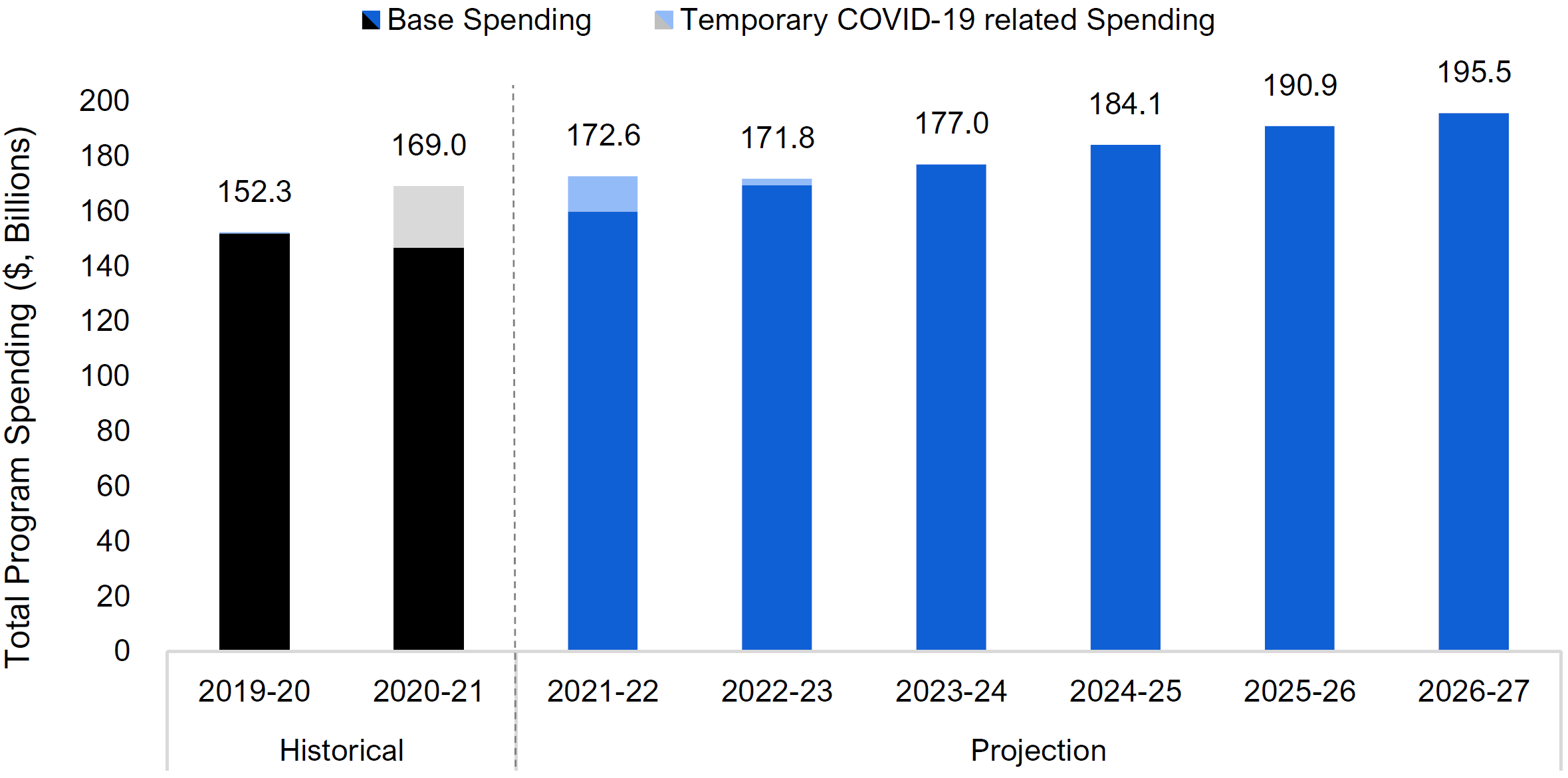

Program spending outlook

Over the seven-year period from 2020-21 to 2026-27, the FAO projects[14] program spending will increase by an average annual rate of 3.6 per cent, led by health sector spending growth.

Total program spending was an estimated $172.6 billion in 2021-22[15] and is projected to decrease to $171.8 billion in 2022-23, as higher base program spending will be offset by an expected $10.4 billion year-over-year decline in temporary COVID-19-related spending.[16]

Under current government programs and policies, the FAO projects that total program spending will reach $195.5 billion in 2026-27, an increase of $43.3 billion from 2019-20 spending levels.

Figure 2‑7 FAO projects average annual program spending growth of 3.6 per cent from 2019-20 to 2026-27

Source: FAO analysis of the 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review and information provided by the Ministries of Colleges and Universities; Education; Finance; Health and Long-Term Care; and Treasury Board Secretariat.

Accessible version

| ($, Billions) | |||

| Year | Base Spending | Temporary COVID-19-related Spending | |

| Historical | 2019-20 | 151.9 | 0.4 |

| 2020-21 | 146.7 | 22.3 | |

| Projection | 2021-22 | 159.8 | 12.9 |

| 2022-23 | 169.3 | 2.5 | |

| 2023-24 | 176.9 | 0.1 | |

| 2024-25 | 184.1 | ||

| 2025-26 | 190.9 | ||

| 2026-27 | 195.5 | ||

Projected program spending growth of 3.6 per cent is higher than the historical average, but there are notable differences across sectors

Total program spending is expected to grow by an average annual rate of 3.6 per cent over the seven-year period from 2020-21 to 2026-27, higher than the 3.4 per cent average annual growth rate during the previous seven-year period from 2013-14 to 2019-20.[17]

At the program sector level, the FAO projects that health sector spending growth will be higher than the historical average (4.8 per cent projection vs. 3.2 per cent historical), while all other program sectors will experience slower spending growth than the historical average.

Figure 2‑8 FAO projects spending growth rate to increase in health sector, slow down in all other sectors

Note: Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (OTPP) expense is included in the education sector.

Source: FAO calculations based on the 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review and information provided by the Ministries of Colleges and Universities; Education; Finance; Health and Long-Term Care; and Treasury Board Secretariat

Accessible version

| Average Annual Program Spending Growth (Per Cent) | ||

| Historical (2013-14 to 2019-20) | Projection (2020-21 to 2026-27) | |

| Total Program Spending | 3.4 | 3.6 |

| Health | 3.2 | 4.8 |

| Education | 4.1 | 2.8 |

| Postsecondary Education | 3.3 | 2.6 |

| Children’s and Social Services | 3.5 | 2.4 |

| Justice | 4.0 | 2.5 |

| Other Programs | 3.3 | 3.0 |

Health spending

Health sector spending is projected to increase by an average annual rate of 4.8 per cent from 2020-21 to 2026-27, significantly higher than the historical spending growth rate of 3.2 per cent from 2013-14 to 2019-20.[18] Highlights include:

- Long-term care homes spending is projected to grow by an average annual rate of 12.6 per cent, reflecting the expected addition of 24,000 new long-term care beds and the hiring of approximately 50,000 additional nurses and personal support workers.[19]

- Hospital spending is projected to grow by an average annual rate of 3.8 per cent, reflecting the expected addition of over 2,000 hospital beds by 2026-27[20] and restrained compensation growth for hospital workers due to the impact of Bill 124[21] on health sector wages.

- OHIP (Physicians and Practitioners) is projected to grow by an average annual rate of 3.6 per cent, reflecting the FAO’s analysis of the new physician services agreement[22] and increasing demand for physician services.

- Community programs and mental health and addictions are expected to grow by an average annual rate of 5.4 per cent and 5.0 per cent, respectively, over the projection, reflecting federal-provincial investments in home care and mental health,[23] permanent wage enhancements for personal support workers,[24] and increasing demand for home care and mental health services.

- Drug program spending is projected to grow by an average annual rate of 5.7 per cent, reflecting increased use of higher cost drugs and growth in the number of Ontarians aged 65 and over, which drives demand for the Ontario Drug Benefit program.

Education spending

Education sector spending is projected to increase by an average annual rate of 2.8 per cent between 2020-21 and 2026-27, lower than the 4.1 per cent rate experienced from 2013-14 to 2019-20.[25] Highlights include:

- Spending by school boards is expected to increase by an average annual rate of 2.2 per cent, reflecting 0.4 per cent annual school enrolment growth, the impact of current education workers’ collective bargaining agreements, which expire at the end of August 2022, and historical wage growth for the remainder of the projection period.

- Child care spending is expected to increase by an average annual rate of 11.1 per cent, reflecting the FAO’s preliminary review of the federal-provincial ‘$10-a-day’ child care agreement announced on March 28, 2022.[26]

Postsecondary education spending

Postsecondary education sector spending is projected to increase by an average annual rate of 2.6 per cent, lower than the historical average of 3.3 per cent. Spending by colleges is projected to moderate due to lower enrolment growth and slower tuition revenue increases from international students.[27] In addition, the FAO projects that student financial assistance spending will grow below historical rates, reflecting program changes announced in 2019[28] and the FAO’s forecast that student / family incomes will increase faster than student educational costs.

Children’s and social services spending

Children’s and social services sector spending is projected to increase by an average annual rate of 2.4 per cent, lower than the historical average of 3.5 per cent. Spending growth for the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) and Ontario Works (OW) is projected to moderate due to lower growth in beneficiary payment rates.[29] However, Ontario Drug Benefit Plan spending is projected to grow above historical rates, and permanent wage enhancements for personal support workers[30] will increase community services spending.

Justice spending

Justice sector spending is projected to increase by an average annual rate of 2.5 per cent, lower than the historical average of 4.0 per cent.[31] Salaries, wages and benefits comprise approximately 61 per cent of spending in the justice sector. The FAO’s projection reflects existing collective bargaining agreements, the impact of Bill 124 for applicable upcoming collective bargaining negotiations, and historical wage growth for the remainder of the period to 2026-27.

‘Other programs’ spending

‘Other programs’ sector spending is projected to increase by an average annual rate of 3.0 per cent, lower than the historical average of 3.3 per cent. Highlights include capital expenditures (largely for transportation), which are expected to grow at an average annual rate of 5.9 per cent, and spending on electricity subsidy programs, which are expected to grow by an average annual rate of 0.4 per cent over the projection.[32]

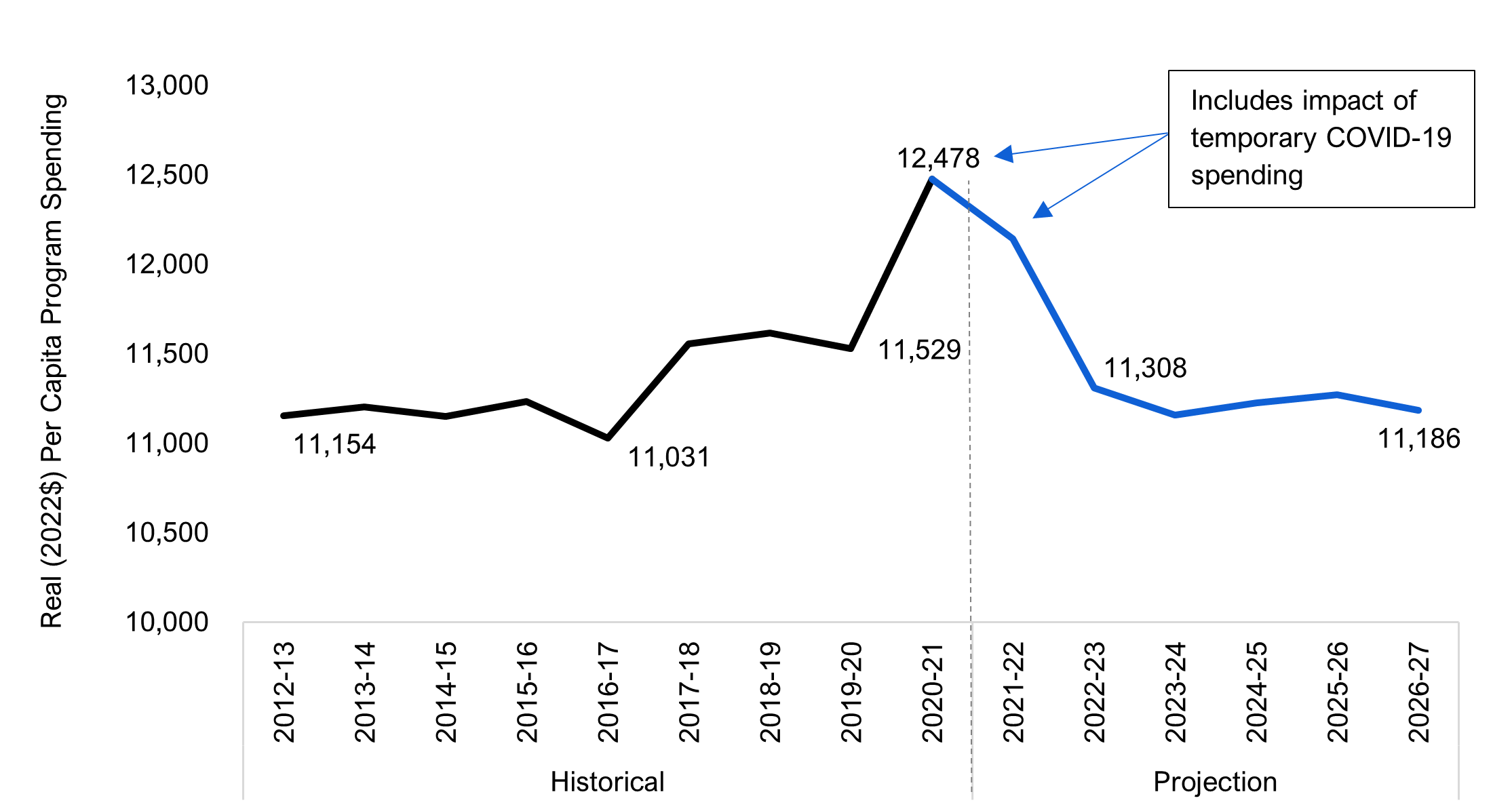

Program spending growth rate is not expected to keep pace with population growth and inflation

The FAO estimates that real per capita program spending[33] was $11,529 in 2019-20 and will decline to $11,186 by 2026-27.

Although total program spending is projected to grow by an average annual rate of 3.6 per cent to 2026-27, the FAO projects that inflation and Ontario’s population will grow at an elevated rate of 4.1 per cent annually,[34] leading to a decline in real per capita program spending.

The FAO projects that total program spending will grow at a rate below population growth and inflation largely due to:

- major government programs that are not directly impacted by the rate of inflation (e.g., payments to physicians [OHIP] under the new physician services agreement, and beneficiary payment rates for Ontario Works and the Ontario Disability Support Program); and

- the FAO’s forecast for wage growth, which reflects existing collective agreements, the impact of Bill 124[35] on applicable upcoming collective agreements, and the FAO’s assumption that wages will follow historical growth thereafter.

However, given that elevated inflation is expected to continue through 2023, upward spending pressure could increase total program spending above the FAO’s projection.

Figure 2‑9 FAO projects real per capita program spending to decline over the projection

Source: FAO analysis of the 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review and information provided by the Ministries of Colleges and Universities; Education; Finance; Health and Long-Term Care; and Treasury Board Secretariat

Accessible version

| Year | Real (2022$) Per Capita Program Spending | |

| Historical | 2012-13 | 11,154 |

| 2013-14 | 11,206 | |

| 2014-15 | 11,151 | |

| 2015-16 | 11,236 | |

| 2016-17 | 11,031 | |

| 2017-18 | 11,557 | |

| 2018-19 | 11,617 | |

| 2019-20 | 11,529 | |

| 2020-21 | 12,478 | |

| Projection | 2021-22 | 12,144 |

| 2022-23 | 11,308 | |

| 2023-24 | 11,158 | |

| 2024-25 | 11,226 | |

| 2025-26 | 11,273 | |

| 2026-27 | 11,186 |

3 | Economic Outlook

Overview

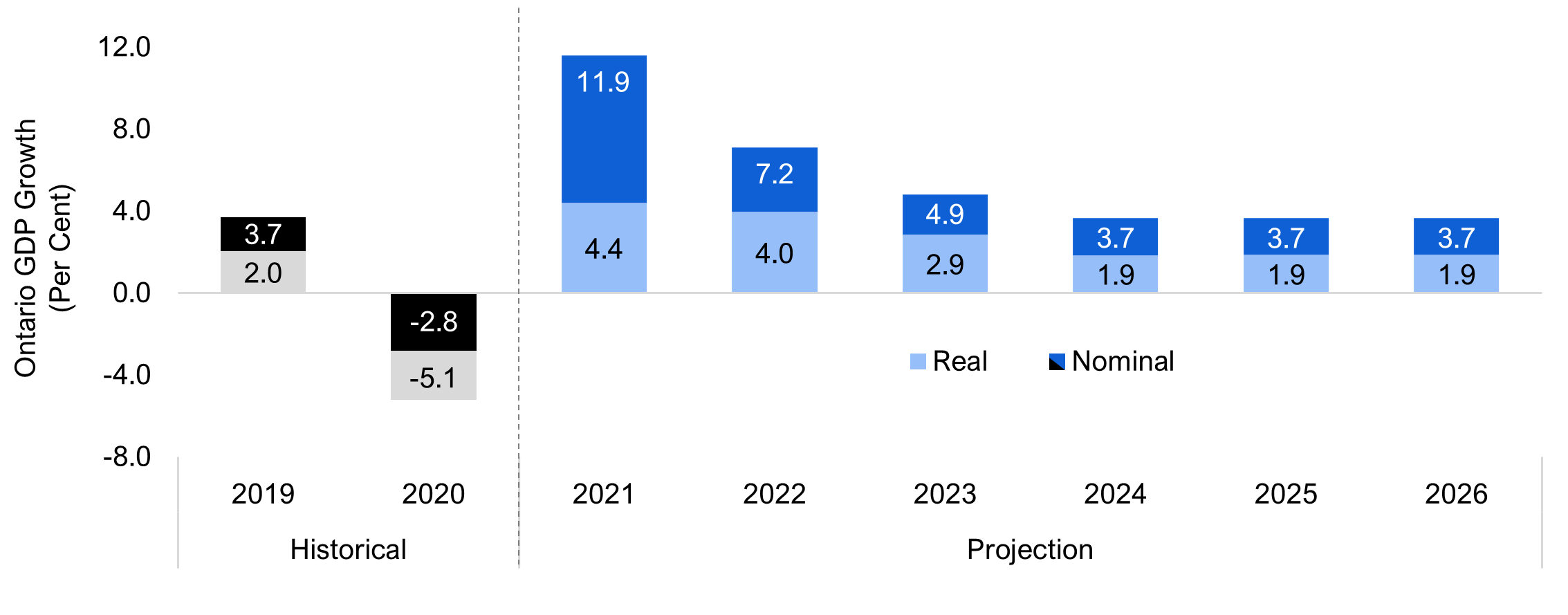

Ontario’s economic growth has been resilient since the recovery began in mid-2020, despite repeated waves of COVID-19 variants. As the economy continues to reopen more fully, consumer activity is expected to pick up, while trade is on the upswing as global demand improves and supply chain constraints are slowly easing. Although global economic growth faces ongoing challenges, including the war in Ukraine, the FAO projects Ontario real GDP will rise by 4.0 per cent in 2022. Ontario nominal GDP, which provides a broad measure of the tax base, is expected to continue expanding well above long-term historical trends, with growth projected at 7.2 per cent in 2022, following an 11.9 per cent surge in 2021.

Significant government spending, historically low interest rates and the increased availability of COVID-19 vaccines provided support for a strong global recovery in 2021. Although global growth is expected to continue at a solid pace, there are downside risks from the possibility of new COVID-19 variants, ongoing price pressures and geopolitical conflict. While the war in Ukraine is expected to have only limited economic impacts in Ontario, higher global energy and food prices have begun to weigh on consumer and business confidence. The rate of economic recovery in many countries is expected to remain uneven as the Omicron variant continues to disrupt economic activity in some regions of the world.

Figure 3‑1 Ontario economy is expected to continue its strong rebound in 2022 and 2023

Source: Ontario Economic Accounts and FAO.

Accessible version

| Ontario GDP Growth (Per Cent) | |||

| Year | Real | Nominal | |

| Historical | 2019 | 2.0 | 3.7 |

| 2020 | -5.1 | -2.8 | |

| Projection | 2021 | 4.4 | 11.9 |

| 2022 | 4.0 | 7.2 | |

| 2023 | 2.9 | 4.9 | |

| 2024 | 1.9 | 3.7 | |

| 2025 | 1.9 | 3.7 | |

| 2026 | 1.9 | 3.7 | |

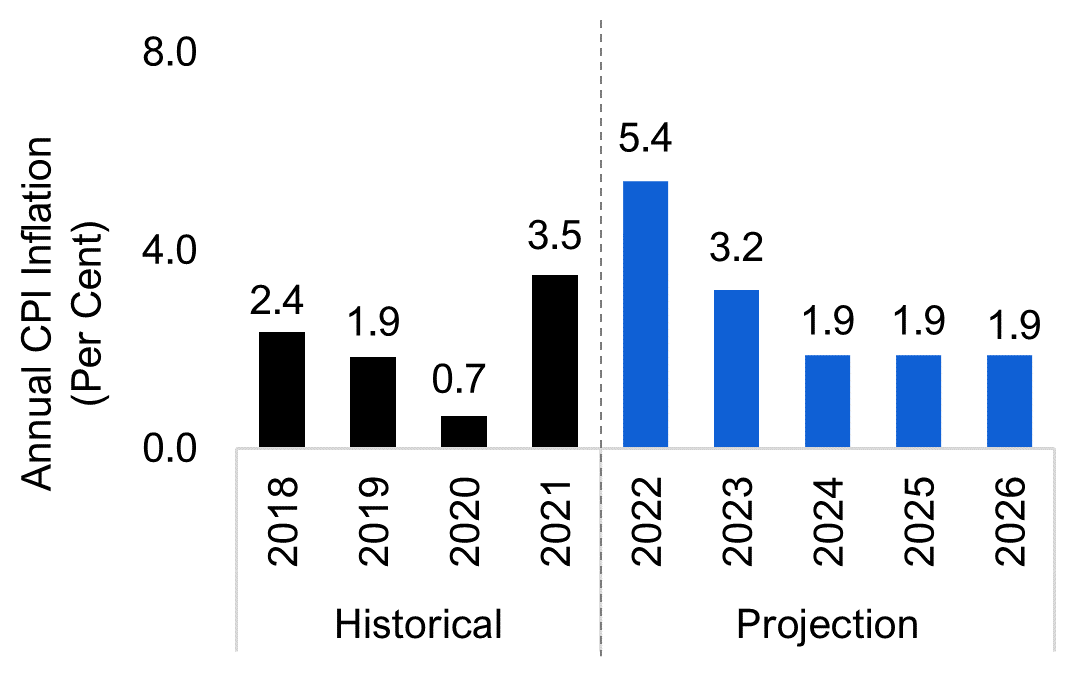

Inflation expected to remain high through 2023

Figure 3‑2 High inflation expected to persist through 2023 in Ontario

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

Accessible version

| Year | Annual CPI Inflation (Per Cent) | |

| Historical | 2018 | 2.4 |

| 2019 | 1.9 | |

| 2020 | 0.7 | |

| 2021 | 3.5 | |

| Projection | 2022 | 5.4 |

| 2023 | 3.2 | |

| 2024 | 1.9 | |

| 2025 | 1.9 | |

| 2026 | 1.9 |

In 2021, supply chain challenges and strong consumer demand contributed to an annual increase in the consumer price index (CPI) of 3.5 per cent, the fastest pace in three decades. In particular, the energy component of the CPI increased by 18.7 per cent in 2021, led by fossil fuel prices. While energy prices are likely to remain elevated due to the war in Ukraine and the rebound in global economic activity, high inflation has become more pervasive, with increases in food, shelter, transportation, and health and personal care costs all accelerating. As a result, the FAO projects an extended period of inflation, with the CPI rising by 5.4 per cent in 2022 and 3.2 per cent in 2023. By 2024, inflation is expected to settle close to historical averages as the economy fully adjusts to higher interest rates.

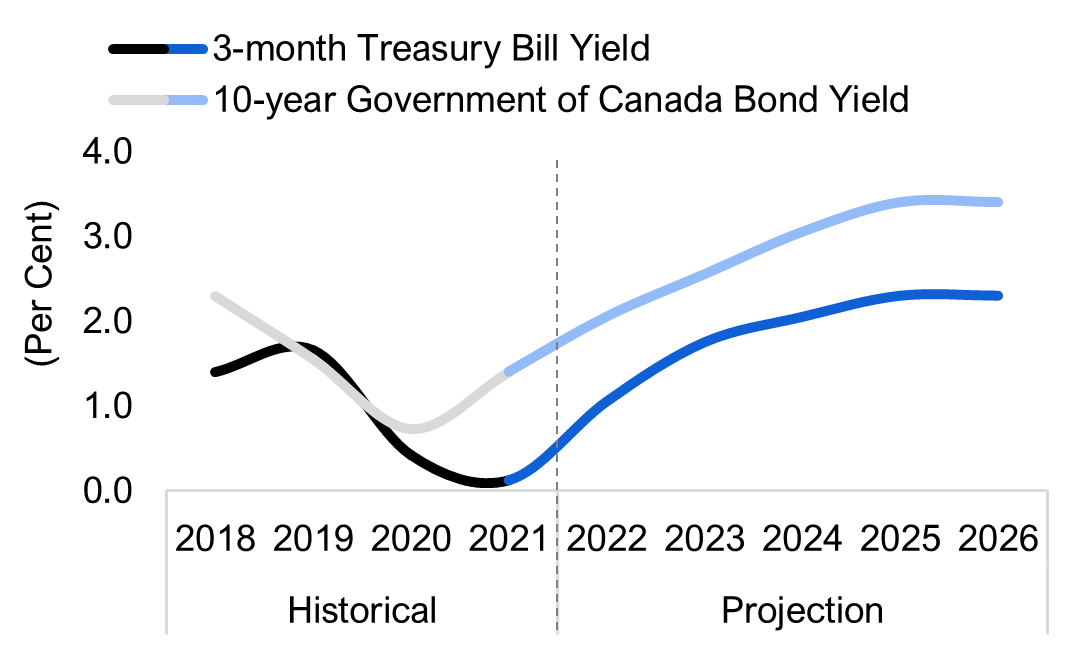

Interest rates to rise quickly over the next few years

Figure 3‑3 Interest rate increases expected to accelerate in 2022

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

Accessible version

| (Per Cent) | |||

| Year | 3-month Treasury Bill Yield | 10-year Government of Canada Bond Yield | |

| Historical | 2018 | 1.4 | 2.3 |

| 2019 | 1.7 | 1.6 | |

| 2020 | 0.4 | 0.7 | |

| 2021 | 0.1 | 1.4 | |

| Projection | 2022 | 1.1 | 2.1 |

| 2023 | 1.8 | 2.6 | |

| 2024 | 2.1 | 3.1 | |

| 2025 | 2.3 | 3.4 | |

| 2026 | 2.3 | 3.4 | |

The Bank of Canada raised its policy interest rate[36] to 0.5 per cent in March 2022 after maintaining the rate at 0.25 per cent for the past two years. In the January 2022 Monetary Policy Report, the Bank projected strong growth in the Canadian economy over the next two years, with inflation slowing gradually in 2023 and 2024 towards the two per cent target. The Bank has since acknowledged that inflation has been stronger than anticipated as high transportation costs, robust housing market activity and the war in Ukraine have pushed key measures of inflation above expectations.[37] Similarly in the United States, the Federal Reserve raised the federal funds rate by 25 basis points in March 2022 and signaled its intention to make larger rate increases if high inflation persists.[38]

The FAO expects interest rates will rise quickly over the next two years. The current projection assumes that the Bank of Canada will increase its policy interest rate to 1.25 per cent by the end of 2022, and that the 10-year Government of Canada Bond Yield will reach 3.4 per cent by 2025.

Ontario economy to continue its strong rebound

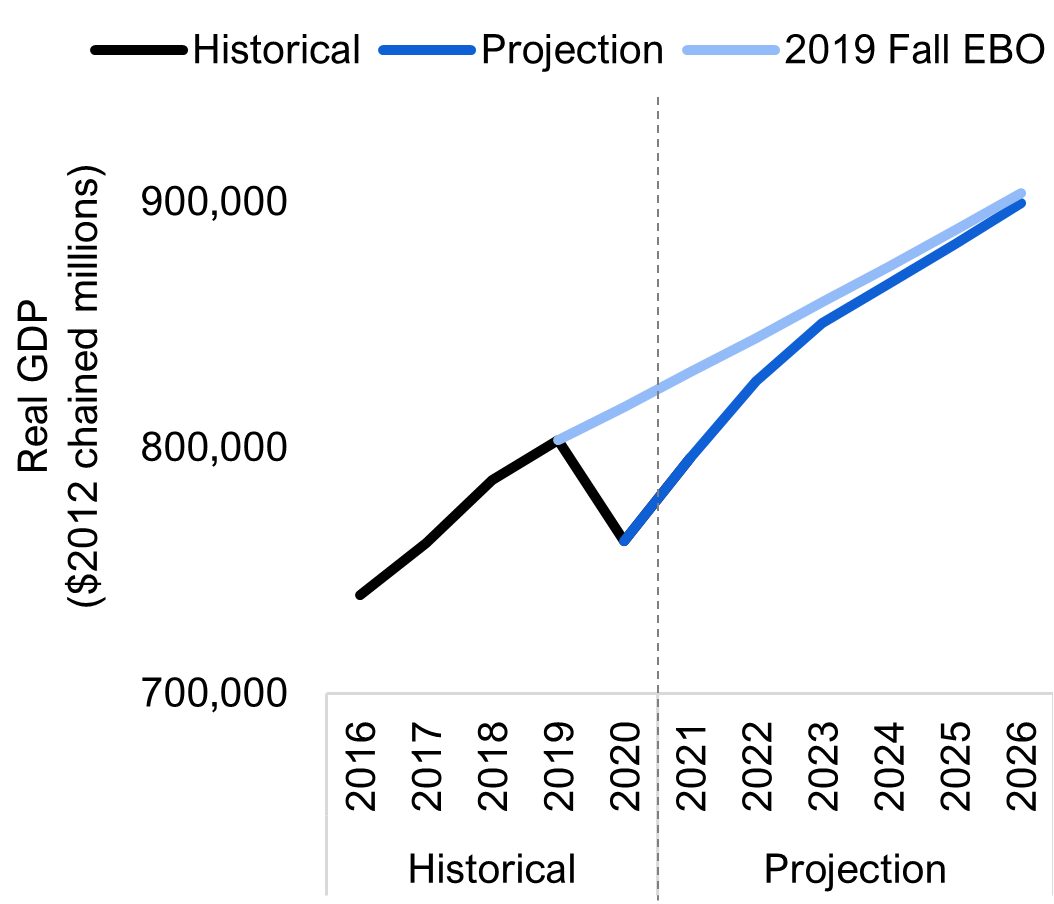

Figure 3‑4 Ontario’s real GDP expected to slowly catch up to the FAO’s pre-pandemic projection

Source: Ontario Economic Accounts and FAO.

Accessible version

| Real GDP ($ 2012 chained millions) | ||||

| Year | Historical | Projection | 2019 Fall EBO | |

| Historical | 2016 | 740164 | ||

| 2017 | 761025 | |||

| 2018 | 786965 | |||

| 2019 | 803088 | |||

| 2020 | 762164 | 816740 | ||

| Projection | 2021 | 795722 | 830625 | |

| 2022 | 827230 | 844746 | ||

| 2023 | 850898 | 859106 | ||

| 2024 | 866683 | 873711 | ||

| 2025 | 882840 | 888564 | ||

| 2026 | 899402 | 903670 | ||

As most pandemic restrictions are lifted and the economy fully reopens, the FAO projects strong economic growth in Ontario over the next two years, with real GDP rising by 4.0 per cent in 2022 and 2.9 per cent in 2023. Over the 2024 to 2026 period, Ontario’s economy is expected to return to long-term trends, with average annual real GDP growth of 1.9 per cent. The level of Ontario real GDP is expected to gradually catch up to the pre-pandemic projection in the FAO’s 2019 Fall Economic and Budget Outlook.

Strong growth is projected for most components of real GDP in 2022. Consumer spending is expected to be resilient, supported by solid wage growth, a strong job market and elevated household savings. Residential investment, which expanded rapidly last year, is expected to moderate in 2022 reflecting in part higher mortgage rates. Following a slow recovery in 2021, exports will benefit from the rebound in manufacturing activity in the United States.

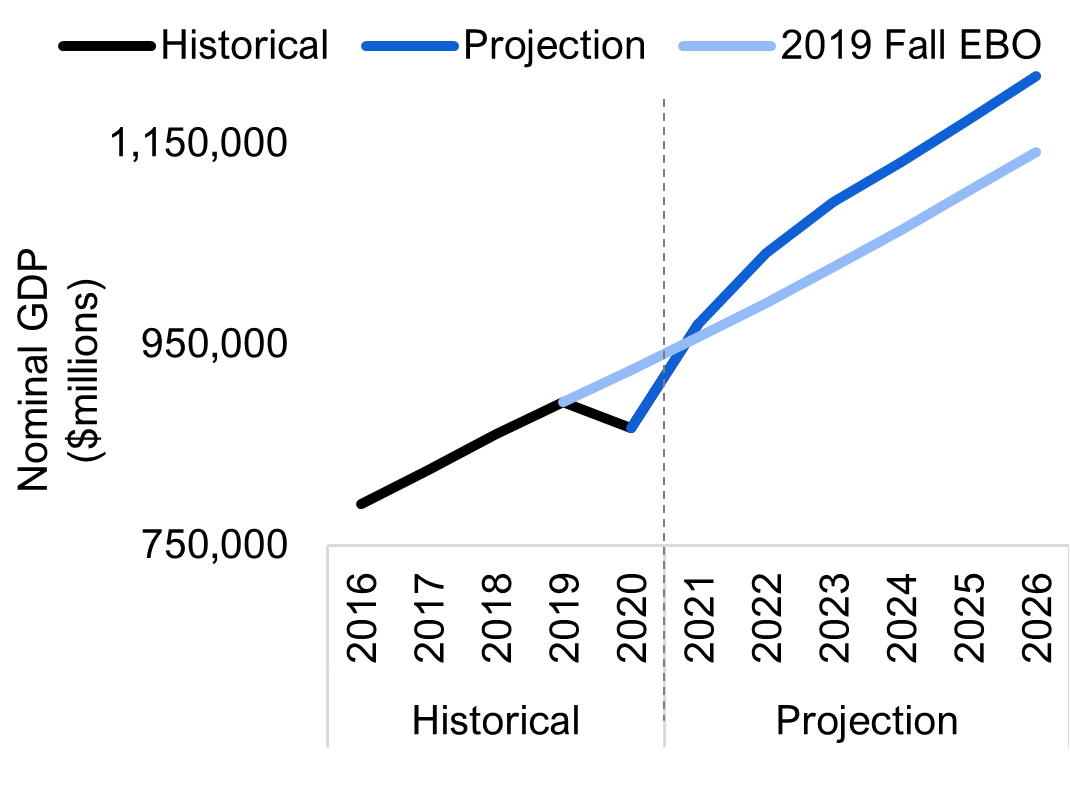

Figure 3‑5 Ontario’s nominal GDP has already surpassed the FAO’s pre-pandemic projection

Source: Ontario Economic Accounts and FAO.

Accessible version

| Nominal GDP ($ millions) | ||||

| Year | Historical | Projection | 2019 Fall EBO | |

| Historical | 2016 | 790749 | ||

| 2017 | 824979 | |||

| 2018 | 860104 | |||

| 2019 | 892226 | |||

| 2020 | 866940 | 924346 | ||

| Projection | 2021 | 970195 | 956698 | |

| 2022 | 1040342 | 991139 | ||

| 2023 | 1091093 | 1026820 | ||

| 2024 | 1131474 | 1063786 | ||

| 2025 | 1173191 | 1102082 | ||

| 2026 | 1216565 | 1141757 | ||

Renewed shutdown measures led to a decline in employment in January,[39] which was promptly followed by strong job gains in February. Ontario’s labour market is on track to record another year of strong growth as the economic recovery broadens to sectors impacted the most by the pandemic, pushing the annual unemployment rate down to 5.7 per cent in 2022. The unemployment rate is projected to remain stable over the remainder of the outlook.

In contrast to real GDP, the level of Ontario’s nominal GDP has already exceeded the FAO’s pre-pandemic projection due to the acceleration in wages, profits and economy-wide prices. By 2026, the FAO expects the level of nominal GDP will be $74.8 billion (or 6.6 per cent) higher compared to the pre-pandemic projection.

Rising employment and tight labour markets will continue to bolster labour income, which could help offset some of the impact of high inflation on household spending. Following a strong rebound last year, corporate profits are projected to moderate in 2022 as businesses adjust to rising borrowing costs and higher commodity prices. Overall, nominal GDP is expected to rise by 7.2 per cent in 2022 and 4.9 per cent in 2023 before returning to long-term trends. This sharp growth in nominal GDP is supporting strong revenue growth over the outlook.

4 | Uncertainties in the Economic and Fiscal Projections

Ontario’s economic and fiscal projections are subject to several uncertainties and risks. Ontario’s economic recovery has generally been resilient, but an escalation in geopolitical conflict, renewed supply chain challenges, higher inflation or repeated COVID-19 outbreaks could lead to weaker economic growth over the next several years. In turn, a weaker economic recovery would lower Ontario’s projected budget balance, as would policy changes such as tax cuts, increased program spending, and higher than expected interest rates.

Economic uncertainties

The war in Ukraine has disrupted global trade and pushed up energy and food prices, adding to the current inflationary challenges. A prolonged conflict would further damage economic growth in Europe and the United States, and negatively impact Ontario’s trade.

Supply chain challenges have eased as ongoing efforts by businesses and policymakers have partially alleviated bottlenecks in ports and land transportation. However, regional pandemic lockdown measures in China and the rise in transportation costs have complicated global supply chain operations. If the U.S. economy is adversely impacted by these factors, the rebound in Ontario’s trade could be muted and prices could rise further than projected.

What was initially considered to be a transitory period of high inflation has now lasted over a year.[40] Many of the factors currently driving inflation cannot be directly addressed through higher borrowing costs, and if inflation is more elevated or prolonged than expected, it would further burden households and businesses with higher costs and slow economic growth.

Budget uncertainties

On top of these risks to economic growth, the FAO’s budget projection is subject to policy uncertainty. If new revenue or spending measures are introduced in the upcoming 2022 Ontario Budget, the FAO’s budget balance projection would change.[41]

In addition, underlying cost pressures from high inflation could impact the deficit over the projection. A period of high inflation could put upward pressure on program spending, including wages. The FAO’s program spending projection reflects existing collective agreements and the impact of Bill 124 for applicable upcoming collective agreements, followed by growth in line with historical averages to 2026-27.

A key risk to Ontario’s fiscal outlook is the future path of interest rates, which affects Ontario’s borrowing costs. Higher than expected interest rates would raise interest costs and lead to a deterioration in the FAO’s outlook for Ontario’s net debt as a share of GDP and interest on debt as a share of revenue, increasing the fiscal vulnerability of the province.

Budget sensitivities

To illustrate the impact of potential policy changes on Ontario’s fiscal projection, the FAO estimated the sensitivity of key budget indicators to changes in three main policy areas: tax revenues, federal transfers and program expenditures. For each policy item, Table 4-1 provides an estimate of the in-year and 2026-27 change in budget balance, the total net debt by 2026-27 (also defined as the change in accumulated deficit), and the change in the net debt-to-GDP ratio in 2026-27.

| Change in budget balance in: | Change in Net Debt/ Accumulated Deficit by 2026-27 | Change in Net Debt to GDP Ratio by 2026-27 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022–23 | 2026–27 | ||||

| Tax Policy* | |||||

| Increasing/decreasing annual income taxes payable by $500 for the average taxpayer | +/-$4.5 billion | +/-$6.2 billion | +/-$26.7 billion | +/- 2.2 ppt | |

| A one percentage point increase/decrease to the 11.5 per cent provincial corporate tax rate[42] | +/-$2.1 billion | +/-$2.7 billion | +/-$12.0 billion | +/- 1.0 ppt | |

| A one percentage point increase/decrease to the 8 per cent provincial HST rate | +/-$4.1 billion | +/-$5.7 billion | +/-$24.7 billion | +/- 2.0 ppt | |

| Federal Transfers* | |||||

| A sustained one percentage point increase/decrease in the growth rate of the Canada Health Transfer[43] | +/-$0.2 billion | +/-$1.2 billion | +/-$3.3 billion | +/- 0.3 ppt | |

| A sustained one percentage point increase/decrease in the growth rate of the Canada Social Transfer[44] | +/-$0.1 billion | +/-$0.4 billion | +/-$1.1 billion | +/- 0.1 ppt | |

| A $1 billion increase/decrease in Federal transfers in each year of the projection | +/-$1.0 billion | +/-$1.2 billion | +/-$5.5 billion | +/- 0.5 ppt | |

| Other Revenue | |||||

| A policy change that permanently adds/removes $1 billion of revenue in 2022-23** | +/-$1.0 billion | +/-$1.2 billion | +/-$5.9 billion | +/- 0.5 ppt | |

| Program Spending* | |||||

| A permanent $1 billion program spending change in 2022-23** | +/-$1.0 billion | +/-$1.2 billion | +/-$5.5 billion | +/- 0.5 ppt | |

| A sustained one percentage point change in the growth rate of health sector spending over the projection | +/-$0.8 billion | +/-$4.9 billion | +/-$13.6 billion | +/- 1.1 ppt | |

| A sustained one percentage point change in the growth rate of education sector spending over the projection | +/-$0.4 billion | +/-$2.9 billion | +/-$6.0 billion | +/- 0.5 ppt | |

| A sustained one percentage point change in broader public sector salaries and wages over the projection | +/-$0.5 billion | +/-$2.8 billion | +/-$8.1 billion | +/- 0.7 ppt | |

5 | Appendix Tables

| (Per Cent Growth) | 2019a | 2020a | 2021f | 2022f | 2023f | 2024f | 2025f | 2026f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal GDP | 3.7 | -2.8 | 11.9 | 7.2 | 4.9 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | |

| Labour Income | 4.4 | -0.3 | 9.3 | 6.4 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | |

| Corporate Profits | -1.3 | 10.2 | 25.2 | 2.3 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | |

| Household Consumption | 3.5 | -7.4 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 | |

| (Per Cent Growth) | 2019a | 2020a | 2021a | 2022f | 2023f | 2024f | 2025f | 2026f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real GDP* | 2.0 | -5.1 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | |

| Employment | 2.8 | -4.8 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | |

| Unemployment Rate (Per Cent) | 5.6 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | |

| CPI Inflation (Per Cent) | 1.9 | 0.7 | 3.5 | 5.4 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | |

| Three-month Treasury Bill Rate (Per Cent) |

1.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | |

| 10-year Government Bond Rate (Per Cent) |

1.6 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.4 | |

| ($ Billions) | 2019-20a | 2020-21a | 2021-22f | 2022-23f | 2023-24f | 2024-25f | 2025-26f | 2026-27f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | |||||||||

| Personal Income Tax | 37.7 | 40.3 | 41.5 | 44.8 | 47.1 | 49.2 | 51.2 | 53.3 | |

| Sales Tax | 28.6 | 26.6 | 30.2 | 32.3 | 34.1 | 35.5 | 36.8 | 38.2 | |

| Corporations Tax | 15.4 | 17.8 | 24.9 | 22.6 | 23.5 | 24.8 | 25.6 | 26.4 | |

| All Other Taxes | 26.5 | 26.2 | 29.1 | 29.4 | 30.2 | 31.2 | 32.1 | 33.0 | |

| Total Taxation Revenue | 108.3 | 110.9 | 125.8 | 129.1 | 135.0 | 140.6 | 145.7 | 151.0 | |

| Transfers from Government of Canada | 25.4 | 33.9 | 29.4 | 30.2 | 31.4 | 34.6 | 37.4 | 38.1 | |

| Income from Government Business Enterprise | 5.9 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 6.9 | |

| Other Non-Tax Revenue | 16.5 | 15.1 | 15.5 | 17.2 | 18.1 | 18.7 | 19.4 | 20.0 | |

| Total Revenue | 156.1 | 164.9 | 176.2 | 182.4 | 190.7 | 200.2 | 209.1 | 216.1 | |

| Expense | |||||||||

| Health Sector | 63.7 | 69.5 | 77.1 | 74.7 | 77.9 | 81.6 | 85.0 | 88.5 | |

| Health (Base) | 63.7 | 62.1 | 69.8 | 73.9 | 77.9 | 81.6 | 85.0 | 88.5 | |

| Temporary COVID-19 Funds | 0.0 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Education Sector | 31.7 | 32.9 | 33.4 | 34.4 | 35.5 | 36.8 | 38.5 | 38.6 | |

| Education* (Base) | 31.4 | 29.4 | 32.0 | 33.7 | 35.4 | 36.8 | 38.5 | 38.6 | |

| Temporary COVID-19 Funds | 0.4 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Children's and Social Services Sector | 17.1 | 17.4 | 16.9 | 17.9 | 18.5 | 19.1 | 19.6 | 20.2 | |

| Children's and Social Services (Base) | 17.1 | 16.9 | 16.5 | 17.9 | 18.5 | 19.1 | 19.6 | 20.2 | |

| Temporary COVID-19 Funds | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Postsecondary Education Sector | 10.5 | 9.8 | 10.3 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 11.7 | 12.2 | 12.6 | |

| Postsecondary Education (Base) | 10.5 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 11.7 | 12.2 | 12.6 | |

| Temporary COVID-19 Funds | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Justice Sector | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 5.6 | |

| Justice (Base) | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 5.6 | |

| Temporary COVID-19 Funds | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Other Programs | 24.5 | 34.6 | 30.0 | 28.6 | 28.4 | 29.5 | 30.0 | 30.1 | |

| Other (Base) | 24.5 | 23.8 | 26.3 | 27.6 | 28.4 | 29.5 | 30.0 | 30.1 | |

| Temporary COVID-19 Funds | 0.0 | 10.8 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Total Program Expense | 152.3 | 169.0 | 172.6 | 171.8 | 177.0 | 184.1 | 190.9 | 195.5 | |

| Total Program Expense (Base) | 151.9 | 146.7 | 159.8 | 169.3 | 176.9 | 184.1 | 190.9 | 195.5 | |

| Total Temporary COVID-19 Funds | 0.4 | 22.3 | 12.9 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Interest on Debt | 12.5 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 12.8 | 13.2 | 13.5 | |

| Total Expense | 164.8 | 181.3 | 184.9 | 184.1 | 189.5 | 196.9 | 204.1 | 209.0 | |

| Budget Balance** | -8.7 | -16.4 | -8.7 | -1.7 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 7.1 | |

| ($ Billions) | 2019-20a | 2020-21a | 2021–22f | 2022–23f | 2023–24f | 2024-25f | 2025-26f | 2026-27f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget Balance* | -8.7 | -16.4 | -8.7 | -1.7 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 7.1 | |

| Accumulated Deficit | 225.8 | 239.3 | 247.9 | 249.6 | 248.4 | 245.0 | 240.0 | 232.9 | |

| Net Debt | 353.3 | 373.6 | 389.6 | 399.8 | 406.1 | 409.7 | 411.8 | 412.2 | |

| Net Debt-to-GDP (Per Cent) |

39.6 | 43.9 | 40.2 | 38.4 | 37.2 | 36.2 | 35.1 | 33.9 | |

Footnotes

[1] See the FAO’s 2018 Hydro One: Updated Financial Analysis of the Partial Sale of Hydro One.

[2] See the FAO’s 2018 Cap and Trade: A Financial Review of the Decision to Cancel the Cap and Trade Program.

[3] These include the introduction of the Low-Income Individuals and Families Tax credit, the Accelerated Capital Consumption Allowance, as well as the reversal of several tax measures introduced in the 2018 Budget. See the FAO’s Economic and Budget Outlook, Fall 2018 for more details.

[4] See the FAO’s 2018 deficit commentary for more details.

[5] In the 2021-22 Third Quarter Finances corporations tax revenue is projected to be $5.3 billion higher in 2021-22 than projected in the Fall Economic Statement due to higher 2020 results and prior year tax assessments.

[6] The federal government has announced $2 billion in one-time health transfers in 2022-23. Based on Ontario’s population share, this represents a one-time increase in federal transfers of about $800 million.

[7] Economic growth measured by nominal GDP, the main driver of tax revenue growth, is projected to average 4.8 per cent per year over 2020 to 2026, compared to the 3.9 per cent average over the 2013 to 2019 period.

[8] See the FAO’s Fall 2018 Economic and Budget Outlook page 15 for details.

[9] The Canada Health Transfer is legislated to grow in line with a three-year moving average of Canada’s nominal GDP, with a minimum increase of at least three per cent per year, and is allocated on a per capita basis by province.

[10] “$13.2 Billion Child Care Deal will Lower Fees for Families,” March 28, 2022.

[11] See the FAO’s 2018 Hydro One: Updated Financial Analysis of the Partial Sale of Hydro One.

[12] See the FAO’s 2018 Cap and Trade: A Financial Review of the Decision to Cancel the Cap and Trade Program.

[13] See the FAO’s 2021 Spring EBO.

[14] The FAO’s program spending forecast is based on the FAO’s projected cost of current government programs and policies, the impact on the health sector of the Omicron wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and new program announcements made since the release of the 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, up to March 28, 2022.

[15] The FAO’s 2021-22 program spending projection is $3.2 billion lower than the Province’s 2021-22 program spending outlook reported in the 2021-22 Third Quarter Finances. Compared to the 2021-22 Third Quarter Finances, the FAO projects lower spending in the postsecondary education, children’s and social services, and ‘other programs’ sectors, and higher spending in the health and education sectors.

[16] The FAO’s spending projection includes an estimated $0.4 billion in COVID-19-related spending in 2019-20, $22.3 billion in 2020-21, $12.9 billion in 2021-22, $2.5 billion in 2022-23, and $0.1 billion in 2023-24. For information on COVID-19-related spending prior to the Omicron wave, see the FAO’s Federal and Provincial COVID-19 Response Measures: 2021 Update.

[17] To remove the temporary impact of COVID-19-related spending, 2019-20 is selected as the base year for program spending growth rate comparisons. Unless otherwise stated, projected program spending growth rates refer to the 2020-21 to 2026-27 period, and historical program spending growth rates refer to the 2013-14 to 2019-20 period.

[18] The 3.2 per cent average annual growth rate from 2013-14 to 2019-20 resulted from health sector spending restraint measures, including freezing hospital operating budgets from 2012-13 to 2015-16 and restraining health sector compensation growth. See FAO, “Ontario Health Sector: An Updated Assessment of Ontario Health Spending,” 2018 for more analysis.

[19] FAO estimate based on the Province’s commitment to add 30,000 new long-term care beds by 2028 and to provide an average of four hours of daily direct care to long-term care residents by 2024-25. For more analysis of the Province’s long-term care commitments, see FAO, “Ministry of Long-Term Care: Spending Plan Review,” 2021.

[20] FAO estimate based on a review of the Province’s 2021 Ontario Budget capital plan.

[21] Protecting a Sustainable Public Sector for Future Generations Act, 2019.

[22] “Ontario government and Ontario Medical Association reach successful agreement to strengthen care,” March 28, 2022.

[23] For more information, see the Canada-Ontario Home and Community Care and Mental Health and Addictions Services Funding Agreement.

[24] “Ontario Introduces a Plan to Stay Open,” March 29, 2022.

[25] Growth in education sector spending from 2013-14 to 2019-20 includes the implementation of full-day kindergarten, significant enhancements to child care programs, including the Child Care Expansion Plan and the introduction of the CARE tax credit, $1.3 billion in one-time savings in 2012-13 related to changes to teachers’ sick leave policy, and temporary COVID-19-related spending of $0.4 billion in 2019-20.

[26] “$13.2 Billion Child Care Deal will Lower Fees for Families,” March 28, 2022.

[27] The FAO estimates college tuition revenue from international students averaged annual growth of 26 per cent from 2013-14 to 2019-20.

[28] “Government for the People to Lower Student Tuition Burden by 10 per cent,” January 17, 2019.

[29] ODSP and OW beneficiary payment rates have not changed since a 1.5 per cent increase in 2018.

[30] “Ontario Introduces a Plan to Stay Open,” March 29, 2022.

[31] Historical and projected justice sector spending growth rates are impacted by $192 million in court settlements in 2019-20. Excluding these payments, historical justice sector spending would have averaged 3.3 per cent annual growth from 2013-14 to 2019-20 and projected spending would be 3.1 per cent, on average, from 2020-21 to 2026-27.

[32] For more information, see FAO, “Ontario’s Energy and Electricity Subsidy Programs: Cost, Recent Changes and the Impact on Electricity Bills,” 2022.

[33] Program spending is adjusted for inflation to a real basis using 2022-23 constant dollars.

[34] From 2013-14 to 2019-20, population and inflation grew by an average annual rate of 2.9 per cent, lower than the 3.4 per cent growth rate of total program spending.

[35] Bill 124, Protecting a Sustainable Public Sector for Future Generations Act, 2019, limits annual compensation growth to one per cent over mandated three-year periods for designated provincial employees, including in the Ontario Public Service, provincial agencies, and hospitals, school boards and colleges.

[36] The policy interest rate is the Bank of Canada’s target for the overnight rate, which is the rate at which major Canadian financial institutions can borrow from one another.

[37] “Bank of Canada increases policy interest rate”, Bank of Canada, March 2022.

[38] Federal Open Market Committee Press Conference, Federal Reserve, March 2022.

[39] For an update on Ontario’s labour market performance in 2021 and the impact of the COVID-19 Omicron variant on the labour market in January 2022, see the FAO’s Ontario’s Labour Market in 2021 report.

[40] Ontario’s year-over-year monthly CPI rose above the Bank of Canada’s two per cent target in March 2021 at 2.2 per cent and has steadily increased to 6.1 per cent in February 2022.

[41] In assessing the 2021 Ontario Fall Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, the FAO found potential unannounced tax cuts of approximately $2.5 billion by 2023-24, which would increase the government’s deficit and lead to higher borrowing, if enacted. See: Budget Outlook Update, FAO, 2022.

[42] The increase in the general Corporations Tax rate also incorporates increases to Manufacturing and Processing Corporations Income Tax Rate and the Small Business Corporations Income Tax Rate.

[43] The Canada Health Transfer is legislated to grow in line with a three-year moving average of Canada’s nominal GDP, with a minimum increase of at least 3 per cent per year and is allocated on a per capita basis by province.

[44] The Canada Social Transfer is legislated to grow at three per cent per year and is allocated on a per capita basis by province.